Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist

By Nava Atlas | On March 24, 2020 | Updated May 21, 2024 | Comments (2)

The 1913 novel Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter (1868 – 1920) is perhaps less familiar now than the lasting expression that grew from its sentimental story.

Most everyone knows what defines a “Pollyanna” — someone who looks at the bright side of things no matter how dire, or who paints an overly optimistic picture of any situation.

Pollyanna, subtitled “The Glad Book,” was incredibly successful from the start, and inspired many adaptations in other media. Though intended as a children’s novel, it appealed to all ages.

Eleven-year-old Pollyanna Whittier, one of a legion of literary orphans, is sent to live with her aunt Polly, an icy spinster. This follows on the trope of another ebullient orphan of that era, Anne Shirley, better known as Anne of Green Gables (1908), who melts the heart of the stereotypical spinster who adopts her.

Introducing the “glad game”

Pollyanna and her departed father had devised a “glad game,” wherein they would try to find the silver lining in any situation, no matter how dire. So when Pollyanna got a pair of crutches for Christmas instead of the doll she longed for, she decided to be glad that she didn’t need the crutches.

Once she is living with her stern aunt, she is punished for being late for dinner and is relegated to eating bread and milk in the kitchen with the servant. No problem for her — she determines to enjoy the bread and milk and to like the servant.

In this essay, Jurrian Kamp muses on Pollyanna’s approach to life:

“The glad game shields her from her aunt’s stern attitude: when Aunt Polly puts her in an ugly attic room with no pictures, rugs or mirrors, she is glad for it.

If she had a nice bedroom, she probably wouldn’t notice the beautiful trees outside her window. Had her aunt given her a mirror, she would have to look at her freckles.”

Soon, Pollyanna is spreading her glad game to the resident of the dour Vermont town in which she now lives, transforming it into a joyous place to live.

. . . . . . . . .

Optimistic Quotes from Pollyanna — and on Being “a Pollyanna”

. . . . . . . . .

A comforting message on the eve of a world war

Sentimental and downright corny as the book can be, its comforting, positive message evidently resonated as the rumblings of World War I were approaching. Its popularity soared all through the war years.

Indeed, the book was an instant bestseller. Newspapers reported that soon after its publication that the book sold more than 150,000 copies, and that the author, “Mrs. Eleanor H. Porter of Cambridge, Mass., is being overwhelmed with letters of appreciation and gratitude.” Within a year, it had sold a million copies.

Building on the enthusiasm for the original, Pollyanna Grows Up was published in 1915.

There are limits to optimism

More than a century after its publication, I still see this expression crop up surprisingly often, and it’s never a compliment. “Such a Pollyanna” is a critical response to someone who is unrealistically optimistic.

Jurrian Kamp argues that there are limits to optimism and that even Pollyanna, in the end, learned not to be so completely a blind optimist:

“Eventually, however, even Pollyanna’s robust optimism is put to the test when she is hit by a car and her legs become paralyzed. Her response, for once, seems realistic.

She is grief-stricken and recognizes that it is easier to tell others to feel good about their plight than to tell oneself the same thing. She admits that the game is not fun if it is really hard to play.

Still, she is determined to find a reason to feel good about her plight. She decides she is glad that she cannot walk because her accident has caused her stern aunt to soften up.

The novel ends happily: the aunt marries her former lover and Pollyanna is sent to a hospital where she learns to walk again, able to appreciate the use of her legs far more as a result of being temporarily disabled.”

. . . . . . . . . .

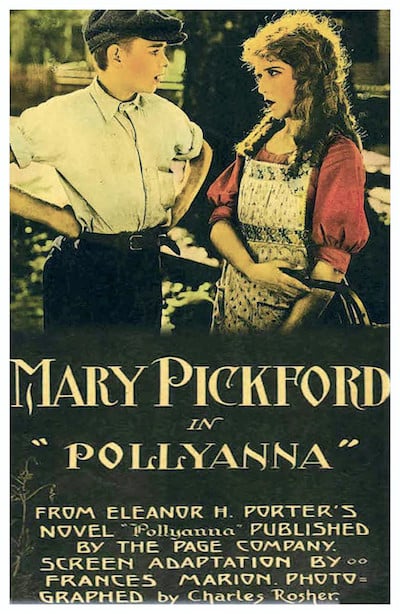

Poster for the first film adaptation of Pollyanna (1920)

. . . . . . . . . .

Sequels and adaptations

Pollyanna’s success led to a sequel, Pollyanna Grows Up, published in 1915. Pollyanna books became a kind of early franchise, with a number of sequels written by authors other than Porter. One even came out as late as 1997: Pollyanna Plays the Game by Colleen L. Reece.

Pollyanna was adapted first for the stage as a comedy called Pollyanna: The Glad Girl. Met with critical and commercial success upon its Philadelphia debut, it toured the U.S. through 1919.

The first film adaptation appeared in 1920 with Mary Pickford in the title role, her first in a storied silent film career. The film, like the play and the book before it, was a smash success.

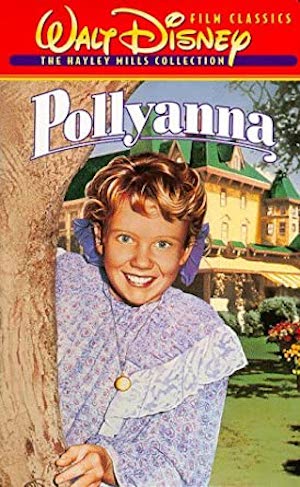

The 1960 Disney adaptation is the best known. Hayley Mills won a special Oscar for her portrayal of Pollyanna. The film departs in some significant ways from the book; still, it was a major success.

In 1973, the BBC aired the story as a six-part series. In 1989, Disney produced a made-for-television musical version with an African-American cast. In 2018, Brazilian telenovela presented a Portuguese language version titled Poliana.

And this is just a partial listing of adaptations. Apparently, something about Pollyanna resonates. Perhaps it appeals to our better natures, the part of us that wants to stay optimistic even in the face of dire situations and the everyday challenges of life.

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1960 film adaptation starred Hayley Mills

. . . . . . . .

How the Pollyanna begins: A synopsis from serialization

Pollyanna was so popular that many newspapers serialized it the year after it appeared. The Baltimore Sun, April 30, 1914, introduced the first installment as follows:

Miss Polly Harrington, a wealthy spinster of forty has led a lonely life for many years in her house in Beldingville, Vermont. She receives the unwelcome news that, by the death of Reverend John Wittier, a poor home missionary and the widower of her late sister, his only child, Pollyanna, has been left an orphan.

Much as she dislikes the idea, Miss Polly considers it her duty to care for her niece. After she has swept the bare little attic room which has been earmarked for Pollyanna, the maid Nancy is sent to meet the small stranger, much to her chagrin.

Miss Polly, now Aunt Polly, receives the impulsive greeting of Pollyanna with icy coldness and the child is moved to tears when she sees the forlorn, hot little room where she must live.

But she meets the situation bravely, telling Nancy about the “glad game” she used to play with her father. It was a game that taught her to find something to be glad about in any trouble no matter how hard to bear.

There are no screens in Pollyanna’s attic room windows, so Aunt Polly won’t allow her to open them for fear of flies. And so, the little girl, who can’t sleep in the stifling heat, tiptoes about and makes her bed on the roof for the night.

Aunt Polly hears the unfamiliar sounds, and calls for Tom and Timothy, the servants, thinking there is a burglar on the roof. She is enraged when the “burglar” proves to bePollyanna, and as a punishment, condemns her niece to spend the rest of the night with her in her bed.

But Pollyanna’s glad game turns the punishment into a reward to the amazement and indignation of her aunt.

During her walks about the town, Pollyanna often meets “The Man.” He looks so lonely that she ventures to speak to him on several occasions and tells him her name. But this only seems to increase his confusion, and he turns and walks away in haste.

With an offering of jelly, Pollyanna is sent to the house of an invalid whose chief business in life is complaining. The little girl wins the cross woman over by combing her curly black hair in a fascinating fashion and persuading her to look at her pretty face for the first time in years.

Pollyanna tries the glad game on the invalid and undertakes to discover for her what there is to be glad about in spending all the long days flat on her back in bed.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The author has the last word

In A 2013 essay in The Atlantic marking the book’s centenary, Ruth Graham wrote:

“Pollyanna’s ‘glad game’ goes beyond simple positive thinking. Pollyanna isn’t always cheerful; she cries over disappointments large and small, and initially refuses to play the game when she suffers a major tragedy. It’s not that she’s naturally the world’s greatest optimist; rather, optimism is a tool she uses to make herself happy.

Her gladness is Gladwellian: It’s not a state of mind, but rather a skill that becomes stronger with practice. As the freckled little guru herself put it, ‘When you’re hunting for the glad things, you sort of forget the other kind.’ Welcome to the 21st century, Pollyanna. You’ll fit right in.”

Despite the book’s incredible success and staying power, Eleanor H. Porter was often roundly criticized for unleashing this cheerful-to-a-fault heroine. In an interview, she explained:

“You know I have been made to suffer from the Pollyanna books. I have been placed often in a false light. People have thought that Pollyanna chirped that she was ‘glad’ at everything. I have never believed that we ought to deny discomfort and pain and evil; I have merely thought that it is far better to ‘greet the unknown with a cheer.'”

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Pollyanna – 1960 film

- Read Pollyanna online at Project Gutenberg

- Listen to Pollyanna on Librivox

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

Recalling the Bobbsey Twins and Their Fictional Author, “Laura Lee Hope”

More Literary Orphan Girls

Hello lovely Ladies, please correct – in 2018, Brazilian tv presented a Spanish language version – it is Portuguese, not Spanish 🙂

Thank you, Flavia — it has been corrected!