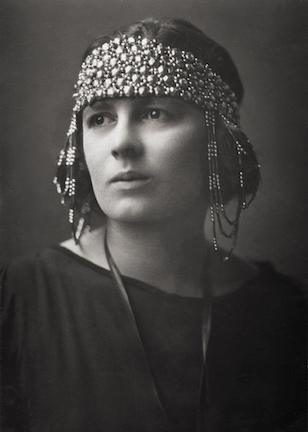

Rebecca West, British Novelist and Journalist

By Nava Atlas | On October 2, 2018 | Updated August 25, 2022 | Comments (0)

Rebecca West (December 21, 1892 – March 15, 1983), British novelist, journalist, and essayist, was born Cicely Isabel Fairfield in County Kerry, Ireland.

Her mother was a pianist; her father, a would-be journalist and ne’er-do-well, abandoned his family when she was eight years old, after which they moved to Edinburgh, Scotland. There she was educated at George Watson’s Ladies College, though contrary to its name, was a secondary school.

At age 14, she survived tuberculosis, and had to end her education at age 16, due to lack of finances. Some time later she studied drama at a London academy. With an unhappy childhood behind her, she assumed the name Rebecca West after a strong-willed woman in Rosmersholm, a play by Ibsen.

Trades and talents, including acting and journalism

West was a woman of many trades and talents early on: she studied to be an actress, started working as a journalist in 1911 at The Freewoman, and was active in the woman’s suffrage movement.

In her work as a journalist, she wrote essays and reviews for publications like New York Herald Tribune, The Daily Telegraph, The New Republic and New York American. Her first book, Henry James: A Critical Biography, was published in 1916.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rebecca West Quotes on Art, Experience, and Human Nature

. . . . . . . . . .

Scathing review of H.G. Wells leads to a love affair

After writing a scathing review of H.G. Wells’ Marriage in 1912, calling him “the Old Maid among novelists,” the two met. The following year they become lovers and had a ten year long affair, which produced a son, Anthony West. Her relationship with both father and son were stormy.

Her son resented her absences from him during his childhood, yet never blamed his father for even more prolonged absences. He rather idolized his father, and grew up to be a talented writer. In a thinly veiled autobiographical novel (Heritage, 1955) he portrayed his mother in a very unflattering light, for which she never forgave him.

Among her other lovers were Charlie Chaplin and Lord Beaverbrook, a newspaper tycoon. As a witty and beautiful woman, men were drawn to her wherever she went on her far-flung travels. In 1930 she married Henry Maxwell Andrews, a banker, and they remained together, though spending much time apart, until his death in 1968.

Novels and non-fiction

In 1918 The Return of the Soldier was published. This, her first novel, was a study of what was then called shell-shock (now more often called PTSD). Her subsequent novels, all considered extremely fine yet undervalued by critics, included Harriet Hume (1929), The Thinking Reed (1936), The Fountain Overflows (1957), and The Birds Fall Down (1966).

. . . . . . . . . .

The Birds Fall Down by Rebecca West

. . . . . . . . . .

Travels and politics

Rebecca West loved travel and politics, both of which figured significantly in her writing. Traveling to countries such as Mexico, Yugoslavia, and South Africa influenced her works, notably Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), considered a classic of literature that spans the genres of travel, culture, and politics.

Other works of nonfiction included The Meaning of Treason (1949), about the role of the intellectual, scientist, and traitor in society; A Train of Powder (1955), which included reports of criminal trials; and The Court and the Castle (1958), which examines how political and religious ideas interact in literature.

In addition to her books, West wrote countless articles and essays for a number of publications on both sides of the Atlantic, including The New Yorker.

A life against tyranny and prejudice

As described in Rebecca West: A Life by Carl Rollyson, “West’s restless, ferocious intelligence took her into every corner of the world in every conceivable genre, and her ability to astonish with what she found there was seemingly never-ceasing. But if her gifts were protean, here agenda was immutable, to make of her life a campaign against tyranny and prejudice.

“A novelist, critic, biographer, travel writer, and investigative journalist, West had a keen eye for conflict, and a razor tongue for battle. Called ‘George Bernard Shaw in skirts’ by pundits, she was a woman both feted for her achievements and feared for her cunning wit — ‘with malice toward all’ was her motto, and her barbs are legend.”

Doris Lessing said of West that she had not been given her due for her vast accomplishments:

“She was the best woman journalist of her time, playing an important role in informing public opinion about extremist politics, both communist and fascist. She wrote one of the most remarkable books of the century, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, about traveling in the Balkans … but it is much more than that, a meditation about the nature of the human animal.”

An original thinker

Rebecca West is considered one of the great minds of the twentieth century. She looked at the human condition with the dispassionate eye of a journalist and the heart of a feminist. For example, from a 1928 speech to the Fabian Society:

“There is one common condition for the lot of women in Western civilization and all other civilizations that we know about for certain, and that is, woman as a sex is disliked and persecuted, while as an individual she is liked, loved, and even, with reasonable luck, sometimes worshipped.”

. . . . . . . . . .

7 Thought-Provoking Views by Rebecca West

. . . . . . . . . .

High honors, and the legacy of Rebecca West

In 1949 she was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and ten years later became a Dame Commander of the Order, hence her oft-used title, Dame Rebecca West. West’s writing won her the Women’s Press Club Award for Journalism in 1948 in the United States.

In 1982, her first novel, Return of the Soldier, was made into a major 1985 film. She was friends and colleagues with numerous other literary, artistic, and political figures of her time.

Dame Rebecca West became increasingly frail and lost eyesight in her last years. She died of old age in 1983, at the age of 90, still bemoaning the fraught relationship with her son on her deathbed. William Shawn, then the editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, wrote upon learning of her death:

“Rebecca West was one of the giants and will have a lasting place in English literature. No on in this century wrote more dazzling prose, or had more wit, or looked at the intricacies of human character and the ways of the world more intelligently.”

All that said, along with the many accolades she received in her lifetime, is her legacy secure? Is she still as widely read as she deserves to be?

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Rebecca West

On this site

Major works

West produced a vast body of work, both fiction and nonfiction. This is but a small sampling of her most enduring.

- The Return of the Soldier (1918)

- The Judge (1922)

- The Thinking Reed (1936)

- Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941)

- A Train of Powder (1955)

- The Fountain Overflows (1956)

- The Birds Fall Down (1966)

Biographies about Rebecca West

- Dangerous Ambition: Rebecca West and Dorothy Thompson by Susan Hertog

- Rebecca West by Victoria Glendinning

- Rebecca West: A Life by Carl Rollyson

More Information

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of West’s books on Goodreads

- Rebecca West’s obituary in the New York Times

Leave a Reply