Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Feminist Author of The Yellow Wallpaper

By Nava Atlas | On April 2, 2018 | Updated August 25, 2023 | Comments (4)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935) was an American author of fiction and nonfiction, praised for her feminist works that pushed for equal treatment of women and for breaking out of stereotypical roles.

She’s best remembered for the semi-autobiographical work of short fiction, The Yellow Wallpaper.

She was one of the leading activists in the late 19th and early 20th century American women’s movement, and her nonfiction works detailing how women’s lives were impacted by social and economic bias are still relevant.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman biography highlights

- After giving birth to her daughter, she suffered from severe postpartum depression, which later informed her best-known work, The Yellow Wallpaper, somewhere between a long short story and a novella.

- After leaving her husband in 1888, a bold move for its time, Charlotte began writing and editing as well as immersing herself in activism. She worked for the suffrage movement as well as labor and socialist causes.

- The Yellow Wallpaper was first published in 1892 and has since been included in numerous anthologies of American literature, women’s literature, textbooks, and of course, anthologies of her own work.

- Shedding a light on women’s social and financial second-class citizenship, Women and Economics, her 1898 book, was also highly influential.

- Her utopian trilogy, Moving the Mountain (1911), Herland (1915), andWith Her in Ourland (1917) are considered groundbreaking works of feminist fiction.

- For a woman who was so progressive on issues like gender equality, it’s disappointing that she marred her legacy by holding racist and anti-immigrant views.

The early life of Charlotte Perkins

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Charlotte was the daughter of Mary Perkins and Frederic Beecher Perkins. When she was an infant, her father abandoned the family. Mary was unable to support Charlotte and her brother, but Frederic’s family came to their aid.

Among the notable Beechers of Hartford were her great-aunts, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Isabella Beecher Hooker, and Catharine Beecher. All were involved in women’s rights causes, and it’s interesting to ponder how much Charlotte was influenced by them.

Charlotte also spent part of her childhood in Providence, Rhode Island. Her formal education was spotty. Her mother showed little affection for her and her brother, yet discouraged them from making friends or reading.

When she was about eighteen, Charlotte reconnected with her absent father, who encouraged her to attend the Rhode Island School of Design. She began taking classes in 1878, and for a time, supported herself as an artist and private tutor.

. . . . . . . . . .

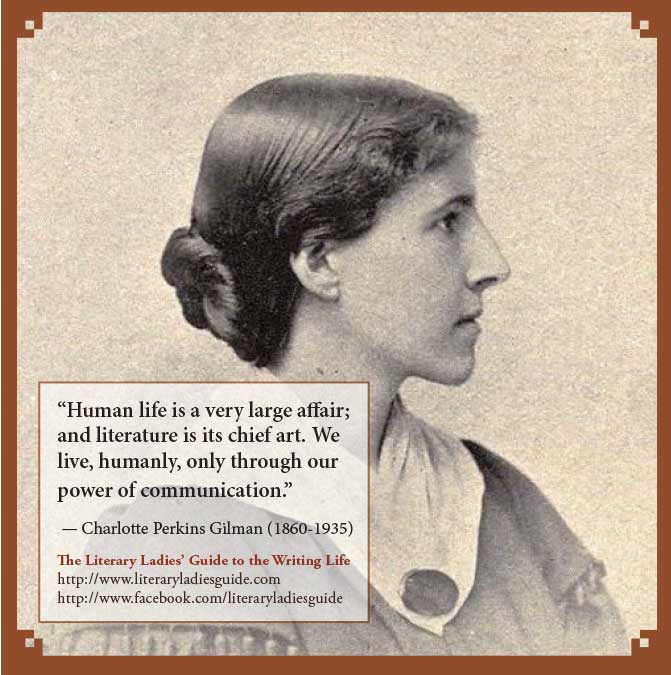

Charlotte Perkins Gilman age 24, 1884

. . . . . . . . . .

Battle with postpartum depression

In 1884 Charlotte married Charles Stetson, an artist. At first, she refused his proposal, sensing that he wasn’t right for her. As it turned out, she should have followed her instinct.

Within their first year of marriage, she gave birth to their daughter, Katharine Beecher Stetson. She succumbed to a serious bout of post-partum depression, exacerbated by the prevailing attitudes that women were frail creatures given to hysteria.

Stetson wasn’t inclined to allow Charlotte any activities to further herself, which exacerbated her already depressed state. This experience was the basis for her 1892 semi-autobiographical novella (or long short story)The Yellow Wallpaper. More on this ahead.

Embarking on a prolific writing career

By 1888, Charlotte left Charles Stetson. It can’t be overstated how rare it was for a wife to leave her husband at the time. She and her daughter Katharine moved to Pasadena, California.

There she become involved with feminist causes, and began writing and editing. She immersed herself in the suffrage movement as well as with labor and socialist organizations.

When Charlotte and husband formally divorced in 1894, he remarried at once. She sent Katharine to live with Charles and his second wife, stating in her memoir that Charles and Katharine had a right to know and love one another. She also felt that Stetson’s new wife would be just as good a mother to Katharine — perhaps even better — than she.

It was during these active, tumultuous years that Charlotte embarked on her path as a serious writer. In 1890, she had her first poem published, and wrote some fifteen essays, a novella, and The Yellow Wallpaper. The latter first appeared in the New England Magazine in 1892.

During these years, she also became a lecturer, which proved to be not only an important source of income, but of connection with like-minded feminists and social activists. She spoke on issues that mattered to her: human rights, women’s issues, labor, social reform, and more.

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her daughter Katharine in 1893

. . . . . . . . . .

The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

What would become Charlotte’s most famous work was written in two days in June of 1890 in her Pasadena home. It was first published in the January 1892 issue of New England Magazine, and has since been included in numerous publications, including collections of American literature, women’s literature, textbooks, and of course, anthologies of her own work.

Charlotte drew on her personal experience with postpartum depression. For the sake of her health, as advised by her husband and physician, the narrator of the story is isolated in a room and becomes fixated on its strange and ugly yellow wallpaper.

The story is a statement on women’s lack of independence and on being at the mercy of physicians and other patriarchal forces, to the detriment of their mental health. You can read the full text here and an analysis here.

Later, in an essay titled “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper” (1913) Charlotte observed:

“For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia — and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country.

This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to “live as domestic a life as far as possible,” to “have but two hours’ intellectual life a day,” and “never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again” as long as I lived.

This was in 1887. I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.”

Women and Economics (1898)

When Charlotte moved back east in 1893, she made contact with Houghton Gilman, a first cousin who was a Wall Street attorney. The two became romantically involved and were married in 1900. She was apparently much happier and more fulfilled in her second marriage. In the intervening years, Charlotte continued to write, edit, and lecture.

She experienced a fair amount of bias as an unconventional mother and as a divorced wife. She began to think about the social forces that oppressed women — even relatively privileged women.

Shedding a light on the economic and social discrimination that forced women into second-class citizenship was the mission of her 1898 book,Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Revolution. This hugely successful book, which was reprinted many times and translated into seven languages, is still, alas, relevant today.

This classic treatise explored the roles of women in American society, particularly on the impacts of marriage and motherhood.

Charlotte argued that motherhood wasn’t exclusive to working outside the home, that domestic tasks ought to be professionalized, and most of all, that women shouldn’t have to be financially dependent on men. It’s now considered a classic treatise from the first-wave feminist movement.

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Perkins Gilman on feminist ideals

. . . . . . . . . .

An influential career

The Home: Its Work and Influence (1903)expanded on the themes inWomen and Economics, and was equally influential.She urged women to rise up in the workforce and extend their lives beyond homemaking and childbearing.

Charlotte wrote, edited, published, and promoted her own magazine,The Forerunner, from 1909 to 1916. In it she presented some of her fiction, including Herland (1915) which would go on to great renown as a feminist utopian novel. It was followed up by With Her in Ourland in 1917.

After closing down The Forerunner, Charlotte wrote hundreds of essays and articles for various publications, and in 1925, began her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which would be published in 1935, just after her death.

Controversial views on race and immigration

Charlotte was so progressive in her views and theories about gender equality that it’s jarring to learn about some of her views on race and immigration. Her views in the 1909 essay “A Suggestion on the Negro Problem” is incredibly racist; there’s no way to sugar-coat it.

And she held rather nationalistic views for someone so dedicated to equality. She had harsh words at times for immigrants, for example, writing that they diluted the “reproductive purity” of Americans of British decent. She famously said of herself “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything,” and has been labeled a “eugenics feminist.”

The later years and legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

In 1932, Charlotte was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer. In 1934, her husband died of a sudden cerebral hemorrhage, and she moved to Pasadena to be near her daughter. The following year, she took her own life by overdosing on chloroform.

Gilman left behind a note stating that she chose chloroform over cancer. Published verbatim in the newspapers, it further read,

“When all usefulness is over, when one is assured of unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one.”

Gilman will always be remembered for her visionary feminist writings, lectures, and passion for social justice and women’s rights. During her lifetime she was a tireless activist and lecturer for the causes she was passionate about.

In 1994 she was welcomed into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and named one of the most influential women of the twentieth century.

Her legacy continues through her powerful literature. Her works are bold and progressive and relatable to future generations of feminists. Unfortunately, her nationalistic, racist, and anti-immigrant stances means that the good that she did needs to be balanced with the harmful aspects of her thinking.

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

More about Charlotte Perkins Gilman

On this site

- 8 Feminist Quotes by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman On Feminist Ideals

- Gilman’s 1911 Version of “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman Quotes

- “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper” (1913)

- Women and Economics (1898) — an excerpt

- The Giant Wistaria — an analysis

- The Yellow Wallpaper — an analysis

- Books by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Full texts on this site

Major Works

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was incredibly prolific. This represents a tiny fraction of her output, which also included essays, stories, and poetry, not all of which ended up in book form.

- The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

- Women and Economics (1898)

- What Diantha Did (1909 –1910)

- The Crux (1911)

- Moving the Mountain (1911)

- The Man-Made World; Or, Our Androcentric Culture (1911)

- Herland (1915)

- With Her in Ourland (1916)

Autobiographies and Biographies

- The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography

- The Abridged Diaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography by Cynthia Davis

More Information

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of Gilman’s books on Goodreads

- The Evolution of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Her Psychology of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

- Managing Madness in Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Beverly Hume

Read and listen online

8 Feminist Quotes by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The Yellow Wallpaper was a harrowing story, very haunting. Leaving your husband in her day was very risky — good for her for having the courage to go. I assume she had no children by her first husband? That would make leaving a lot easier (though not easy!)

I love CPG and wish she was better known today. She was brilliant and so far ahead of her time. I’m reading Herland, and loving it. She did have a daughter with the first husband and gave up custody to him and his new wife. As you can imagine, she was slammed for doing that. But if I’m correct, she and her daughter had a good relationship later on. Thanks for the comment, Susan!

Certainly a great pioneer of Feminism. But a racist at the same time.

True, and an unfortunate blot on her reputaion.