Alice Allison Dunnigan, Trailblazing African American Journalist

By Nava Atlas | On October 3, 2018 | Updated February 11, 2025 | Comments (0)

Alice Allison Dunnigan (April 27, 1906 –May 6, 1983), better known as Alice Dunnigan, was the first African American female correspondent to receive White House credentials.

She was also the first Black female member of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives press galleries. She covered Harry Truman’s 1948 presidential campaign, another first for an African American female journalist.

A true trailblazer, Alice Dunnigan was known for her tough, forthright questions. Her gutsy approach led her from journalism into a position that spanned the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

It was an exciting occasion when the Newseum in Washington, D.C. unveiled a life-size statue of Dunnigan in 2018, honoring her contributions to American journalism.

Following a brief exhibit at the Newseum (which has since closed permanently), the statue was moved to Alice’s hometown of Russellville, KY, where it has been installed on the grounds of the West Kentucky African American Heritage Center, a venue dedicated to the civil rights movement.

A top student and a dedicated teacher

As a girl growing up in Russellville, a rural Kentucky town, Alice dreamed of traveling the world as a reporter. By age thirteen, she had her sights set on the profession. For the daughter of a sharecropper and laundress in 1919, it was a daring ambition.

Alice’s hunger for education drove her to walk the many miles to the segregated schoolhouse she attended, where she was always a top student. When it came time for college, she found few doors open to her as a Black student in the 1920s. When she came upon a rare chance to get into a teacher’s college, she jumped at it.

In the segregated classroom where she wound up teaching, Alice passed along pride in the accomplishments of Black Kentuckians to her students. With her own funds, she printed and distributed pamphlets on the subject to her students.

She taught for nearly two decades, was briefly married (becoming Alice Dunnigan), had a son, and divorced. Pay for Black teachers was meager, so she did laundry, cleaning, cooking — anything to make ends meet.

Though Alice loved teaching, she never forgot her original ambition of becoming a journalist. She wrote for newspapers on the side, publishing articles and stories in various Kentucky newspapers.

Starting anew in Washington, D.C.

As the U.S. entered World War II in the early 1940s, there was an increased need for government workers. Alice moved to Washington D.C. and was hired as a clerk-typist. She worked by day and took courses in journalism at Howard University at night.

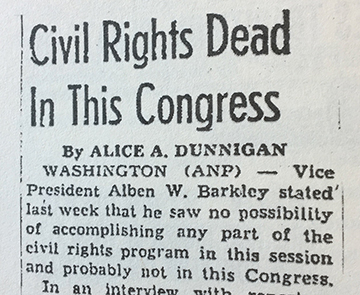

After the war, Alice’s first job was as Washington correspondent for the Chicago Defender, a leading Black newspaper. She gained press access to the Senate and House of Representatives to cover politics and civil rights for the paper.

While she wrote about the segregation laws plaguing Black Americans in the 1940s and 1950s, she often faced discrimination herself. She wasn’t allowed into certain buildings to report on President Eisenhower, and when President Taft died, she was forced to sit with servants while covering his funeral.

Despite those frustrations, by the late 1940s, Alice had achieved her girlhood dream of seeing the world through her work as a journalist. She traveled all over North and South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East.

Still, in her quest to be an excellent journalist, she struggled financially. Her jobs didn’t always pay well, and she was sometimes even compelled to fund her own travels. Still, she prevailed, with the belief that the work she did as a reporter and correspondent was worthy and important.

. . . . . . . . . .

President Harry S. Truman speaks with Alice Dunnigan

. . . . . . . . . .

Eisenhower refused to call on her

For Black reporters accredited to the White House, it was a good opportunity to raise questions and get a direct reply on civil rights issues. It worked fairly well with Truman, with whose campaign she had traveled in 1948. He’d either say “no comment” or give a concise answer.

Not so when Eisenhower became president in 1952. Not particularly friendly to anti-discrimination legislation, he became quite annoyed, and increasingly irate, when she raised such issues.

Some time in 1954, Alice posed a question on discrimination at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. She asked the president if he planned to take any steps recommended by the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). Eisenhower was infuriated.

A conservative columnist wrote a critical analysis of the questions raised by Alice and her colleague, Ethel Payne, writing, “the two gal reporters are hell-bent on competing with each other to see which one can ask President Eisenhower the longest questions.”

Eisenhower seemed to make up his mind never to call on Alice again. She went to every press conference and jumped to her feet between every question, just like all the reports. But the president just ignored her. This went on for a year, then another, until other news outlets started to notice.

The New York Post, ANP (Associated Negro Press), and The Daily Worker picked up the story, and it spread around the nation.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Recognized and appreciated by John F. Kennedy

The presidential boycott of Alice Dunnigan ended with the Eisenhower years. When she was called on by President Kennedy at his first live press conference on January 5, 1961, the headline in Jet magazine read, “Kennedy In, Negro Reporter Gets First Answer in Two Years.”

The story read: “… at his first nationally televised press conference, President John F. Kennedy “quietly scrapped a longstanding White House policy” which was to “ignore veteran correspondent Alice Dunnigan at press conferences.”

After that, she received letters and telegrams from people who had seen her on television, congratulating her for being the first Black reporter to ask the new president a question, as well as the first female reporter to do so.

With controversy behind her, Alice said, “I continued my normal routine of covering White House press conferences.” Alice was an avid proponent of a vibrant Black press:

“Without Black writers, the world would perhaps never have known of the chicanery, shenanigans, and buffoonery employed by those in high places to keep the Black man in his (proverbial) place by relegating him to second-class citizenship.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 10 Pioneering African American Women Journalists

. . . . . . . . . .

A presidential appointment

Soon after, she left journalism to embark on her third act. President Kennedy was so impressed with her that he appointed her as an educational consultant on an important committee, making her the first Black woman to be appointed to the new administration.

Dunnigan served on the new President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity as an educational consultant. She continued that work with the next First Lady, Mrs. Johnson, touring the country with her to visit schools and report on their progress.

She logged many miles in that position, but it was somewhat easier than the roads she’d paved as a journalist.

In 1970, after serving nine years on that committee as well as the President’s Council on Youth Opportunity, she “walked out of the federal government, out of the political arena, out of journalism, out of that mad, mad, world of work, and into the serenity of a quiet, comfortable home life where there is peace, contentment, and happiness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

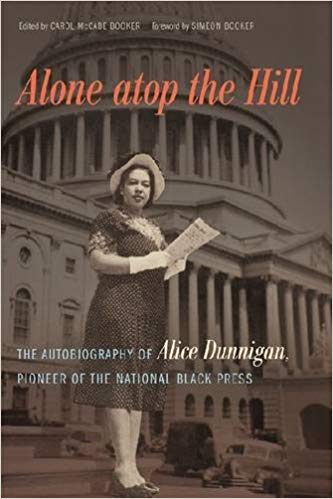

Alone Atop the Hill by Alice Dunnigan on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Alice Dunnigan

After Alice retired, she wrote her life story, A Black Woman’s Experience: From Schoolhouse to the White House (1974). A newer version of the book now called Alone Atop the Hill, came out in 2015. Her hope for her legacy was this:

“It is my fondest hope that the story of my life and work will by interpretation, investigation, information, and inspiration, encourage more young writers to use their talents as a moving force in the forward march progress and that their efforts will soon result in giving Americans the kind of nation that those of my generation so long hoped and worked for.”

With her steely determination and love of learning, Alice Allison Dunnigan was always willing to fight for race and gender equality. She said, “I hope to live to see an ordinary woman go as far as an ordinary man. A woman has to work twice as hard.” And this, too: “Race and sex were twin strikes against me. I’m not sure which was the hardest to break down,”

Alice Dunnigan won more than 50 awards for her work in journalism. In 1985, two years after she died, she was inducted into the Black Journalist Hall of Fame. She died in Washington, D.C., in 1983.

. . . . . . . . . .

Alice Dunnigan’s famous firsts

Alice Dunnigan was the first African American woman:

… to gain press credentials to the White House.

… to travel with the US president (Truman) on a campaign.

…to get press access to the House and Senate galleries, Department of State, and the Supreme Court.

…to be voted into the White House Newswomen’s Association and The National Women’s Press Club.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply