Turning Twelve: Making Room to Grow in The Long Secret by Louise Fitzhugh

By Marcie McCauley | On May 10, 2019 | Updated September 8, 2022 | Comments (0)

“What in the world has happened to Beth Ellen?” Harriet wonders, just a few pages from the end of Louise Fitzhugh’s classic 1964 novel, Harriet the Spy. Harriet is still eleven years old and she sometimes still calls her friend ‘Mouse,’ but Beth Ellen comes into her own as a character in the 1965 novel, The Long Secret.

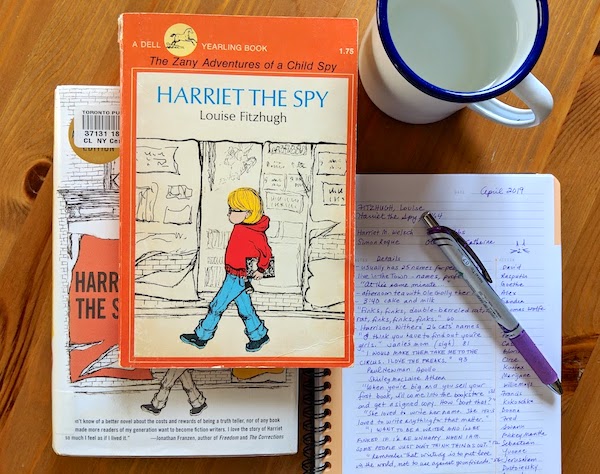

The Toronto Public Library has eighty-two copies of Harriet the Spy (1964) but only six copies of what was billed as the “Further Adventures of Harriet the Spy” — The Long Secret by Louise Fitzhugh, which was published the following year, and only two copies of Sport (1979).

So it seems that the average reader is more interested in Harriet than her friends. That was true for me as a girl as well; I read Harriet the Spy countless times, but I only read The Long Secret once. Which is strange, because I’ve known Beth Ellen almost as long as I’ve known Harriet.

Re-encountering Beth Ellen

Readers meet Beth Ellen first in Harriet’s notebook, in Harriet the Spy, back when Harriet had only a single notebook:

“MAYBE BETH ELLEN DOESN’T HAVE ANY PARENTS. I ASKED HER HER MOTHER’S NAME AND SHE COULDN’T REMEMBER. SHE SAID SHE HAD ONLY SEEN HER ONCE AND SHE DIDN’T REMEMBER IT VERY WELL. SHE WEARS STRANGE THINGS LIKE ORANGE SWEATERS AND A BIG BLACK CAR COMES FOR HER ONCE A WEEK AND SHE GOES SOMEPLACE ELSE.”

In The Long Secret, Harriet keeps two notebooks, “the one regularly used for spying and a new one for writing”. And there is so much more to know about Beth Ellen. Also, so much to learn about Harriet, now that readers are in Beth Ellen’s head as often as Harriet’s. Readers are afforded a place in the narrative which provides perspective on both girls.

So, Harriet says to Beth Ellen: “I’m going to be a writer and I have to have something to write, don’t I? I’m not like you, going and looking at people just because I think they’re nice.”

And Beth Ellen thinks about Harriet: “How odd she is, anyway. What possible fun could it be to write everything down all the time? So tiresome.”

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy

Playing Town: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy

. . . . . . . . .

Harriet’s consistency: Comforting and frustrating

From Beth Ellen’s perspective, Harriet’s consistency is both comforting and frustrating: “Oh, Harriet, thought Beth Ellen, you are always Harriet.”

And there is still a little Mouse in Beth Ellen too: “There was something about the good-natured, bearlike rough-and-tumble of the Jenkins family that made her feel nervous and somewhat frightened. They made her want to hide so they wouldn’t suddenly notice hr and jump on her or make her play some wild outgoing game.”

The Jenkins family lives in Water Mill, New York too. It’s the town of Water Mill which brings Harriet and Beth Ellen together. They do attend the same school in Manhattan, but Harriet is friends with Janie and Sport there.

Harriet is vacationing with her parents and Beth Ellen is there with her grandmother, and although Janie makes an appearance in the story, The Long Secret offers not only a change of scene but a commentary on the change. It deliberately reorients readers and provides another view of one character they thought they knew very well (Harriet) and insight into another character they barely knew (Beth Ellen).

An unpredictable sequel

The Long Secret challenged readers who were accustomed to traditional series, in which the focal point remained predictable. Enid Blyton’s Famous Five and Carolyn Keene’s Nancy Drew series displayed characters in a suspended time, where it was endlessly summer and everyone was too busy solving mysteries to age. In contrast, Louise Fitzhugh’s characters confront change and readers view the shifting landscape from within and without.

Change is uncomfortable and uncertainty is threatening, as Beth Ellen’s questions about menstruation reveal: “Isn’t that right? Aren’t there little rocks that come down and make you bleed and hurt you?” Beth Ellen is twelve and so is Janie, whose scientific knowledge upstages this interpretation of events which Beth Ellen’s grandmother has offered in lieu of facts.

Janie explains that the Victorians who raised Beth Ellen’s grandmother “thought that telling her this was better than telling her the truth.”

Janie opts for the truth and her talk of uterine linings and Fallopian tubes provides some decisive answers but also introduces other challenging questions. Do biological distinctions dictate different life choices for women? Is there a price to be paid for these differences, a price which extends beyond a few days each month to how women occupy the rest of their lives? And how can children make sense of things when the adults in their lives are not equipped to answer difficult questions?

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

What do we do with unanswerable questions?

What are children to do when the adults in their lives are unable or unwilling to tell the truth. Harriet wonders: “Isn’t there some way to force parents to tell the truth? They’re always telling us to tell the truth and then they lie in their teeth.”

What are children to do when they realize that the adults in their lives are making it up as they go along. “I just mean that I have made up my own set of ethics and don’t take them from any organized religion,” explains Harriet’s father.

And what does a writer do for her characters when faced with a question that doesn’t have an answer. Harriet struggles with this dilemma when she writes a story about a mystery in Water Mill: “BUT HOW CAN I HAVE HIM SOLVE IT WHEN I CAN’T EVEN SOLVE IT?”

On the surface, Harriet is preoccupied with a specific mystery: who is leaving notes with quotations from the Bible for town people. (This is a delightful reversal of what occurs in Harriet the Spy, where a serious problem revolves around something that Harriet has written, when everybody realizes what she has written; here, the problem revolves around things that are written which appear to have no author. In one instance, readers know who is judging and, in the other instance, readers do not know: in both cases, people’s feelings are hurt.)

Beneath the surface, all the characters are preoccupied with questions that seem unanswerable. What do we do when our parents (and other adults) are absent or disappointing? What do we do when we realize that our parents are just ordinary people? What do we do with unanswerable questions?

A space for readers to locate themselves

The Long Secret does contain some answers, however. And not only about how menstruation works and how one can create their own system of ethics outside of organized religion.

Readers also learn more about that “someplace else”, that place where Beth Ellen went in Harriet the Spy, and that everyone has a “someplace else” even if not everyone gets to see it. Perhaps more importantly, readers learn how to find security in an ever-changing world: “She felt a rush of love, a safety and a joy in the simple warm routine of bed, […] of her own room, of herself.”

And perhaps most importantly, readers learn that change might be hard, and lies might be frightening, but change is good: something to prepare for, something to anticipate, something to welcome. “I will be different in the morning, she thought with a feeling close to contentment, and rolled over on her side into sleep.”

Whether in Manhattan or Water Mill, Louise Fitzhugh leaves a space for readers to locate themselves in her story. And the comfort of story? It simultaneously takes you someplace else and roots you where you are: it reminds you that being yourself is not always easy but always essential.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

Leave a Reply