10 Fascinating Facts About Louisa May Alcott, Author of Little Women

By Nava Atlas | On November 29, 2019 | Updated September 2, 2022 | Comments (0)

Louisa May Alcott (1832 – 1888) may be best known as the author of Little Women and its sequels, but there was more to her than these genteel (yet gently subversive) domestic tales. The fascinating facts about Louisa May Alcott that follow might surprise those who don’t know a lot about the woman behind Little Women.

From her teen years on, Louisa was determined to make a living as a writer. She became the Alcott family’s primary breadwinner at a young age, mostly by writing and selling anonymous thrillers, or what she called “blood and thunder” tales.

And from there her writing life unfolded, often in unexpected ways. She was a complex woman whose views were reflected in her literary output.

. . . . . . . . . .

She never went to school and grew up “free-range”

Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, Louisa grew up in Boston and then in Concord, Massachusetts. In a sketch of her childhood, she recalls the delights of “running away” and being allowed to wander around Boston by herself from a very young age.

Always self-identified as a tomboy, she adored running and even wrote that she “must have been a deer or a horse in some former state, because it was such a joy to run.” She never had a formal education other than getting lessons from her father, yet she grew up absorbing the world she grew up in.

. . . . . . . . . .

Louisa wrote thrillers to help support her family

Especially at the start of her writing endeavors, Louisa produced a large body of thrillers (otherwise known as gothic or sensational tales) whose sales supported her family. Amos Bronson Alcott was an impractical philosopher without any talent for earning money.

Her beloved mother, Abigail May Alcott, did whatever work a woman could get to put food on the table. Louisa wanted nothing more than to ease her “marmee’s” burden.

Using various pseudonyms, Louisa seemed to take perverse pleasure in dark themes, returning to the genre even after financial need no longer compelled her to do this sort of formula writing. The first modern compilation of what Louisa called “blood and thunder tales” was Behind a Mask: The Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott, published in 1975.

. . . . . . . . . .

She promoted women’s rights and abolition

Her views were often expressed by the female characters in her books, strong young women who wanted more from life than to get married and have babies. Louisa May Alcott expert Susan Bailey explains that: “Louisa’s feminism was based on autonomy – the right of every woman to be autonomous, the freedom for each woman to realize her true potential as a whole person.”

Louisa contributed to a women’s rights periodical in the 1870s. At the end of the decade, Massachusetts passed a law allowing women to vote in local elections. Louisa registered at once, becoming the first woman to vote in Concord.

She and her family were also ardent abolitionists, a view that was not as widely popular in relatively liberal Massachusetts as one would think. Her father had been one of the earliest abolitionists, having joined the American Anti-slavery Society with William Lloyd Garrison. One of her early memories was of the fugitive slave whom her mother had hidden in their oven.

. . . . . . . . . .

Louisa served briefly as a Union nurse during the Civil War

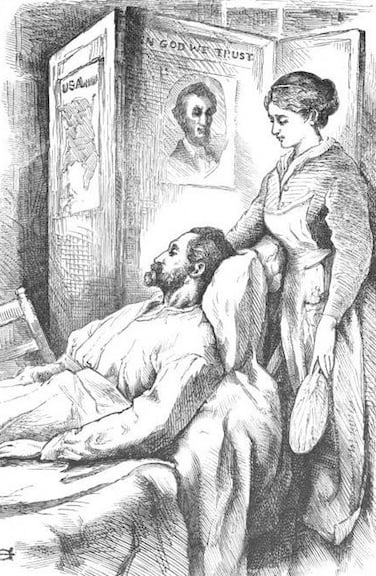

“I WANT something to do,” she wrote of her desire to contribute to the Union Army’s effort. If women had been allowed to serve as soldiers, Louisa would have surely taken up arms.

But as it was, the only direct way women could serve was to volunteer as nurses, and that’s just what she did, dispatching herself to serve at the Union Hotel in Washington, D.C., which had been turned into a makeshift hospital.

Not even a month into her service, Louisa came down with typhoid pneumonia, complete with a horrendous cough and a high fever. She was taken home and suffered a long, grueling recovery; the illness may have caused permanent damage to her health. Yet from her brief stint, Louisa was able to convert the journals she kept into a book called Hospital Sketches, which was a modest success.

. . . . . . . . . .

She was reluctant to write a “girl’s story”

The first novel Louisa published under her real name was Moods. Published in 1864, it followed the modest success of Hospital Sketches. But the reception of Moods was disappointing.

Tired of churning out sensational tales, Louisa felt a bit adrift as a writer. In 1868, her publisher offhandedly asked her to try writing a “girls’ story” for their list. She cranked out the semi-autobiographical (albeit idealized) novel in two and a half months, though her heart wasn’t in it.

At first, neither Louisa nor her publisher thought the book was in any way remarkable. Yet it truly was an overnight success, with no one more surprised Louisa, who came to appreciate its merits.

. . . . . . . . . .

Many women writers have been inspired by the fictional Jo March

Jo March, the standout sister among the quartet in Little Women, is one of the most iconic and influential female characters in literature. Tomboyish and ambitious, with a bit of a temper, she was an idealized alter ego of her creator, Louisa May Alcott.

Many women writers, famous and otherwise, have named named Jo as a major inspiration. Here are 10 of them, from Simone de Beauvoir to Patti Smith.

. . . . . . . . . .

Louisa was alarmingly naïve about her sexuality

Despite all that she’d seen in life, Louisa confessed in an 1883 interview: “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body … because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.”

Perhaps unknowingly, the repressed nature of her sexuality helped her avoid the circumscribed path of marriage and motherhood, and allowed her to view the institution dispassionately.

. . . . . . . . . .

One of her thrillers was rediscovered and published in 1995

A Long Fatal Love Chase (1866) stands squarely in the “woman in peril” genre — it’s a chilling portrait of a woman being stalked by an unstable husband. This novel would be the longest and last of Louisa’s “sensation tales.” Written under the pseudonym A.M. Barnard, it would take nearly 130 years for it to see the light of day again, and to be attributed to its now-famous author.

Thriller master Stephen King, reviewing A Long Fatal Love Chase in the New York Times, concluded:

“Genius burned for Louisa May Alcott following A Long Fatal Love Chase, brightly but never again with such primitive and joyful heat.

One wonders what kind of writer she might have been had she been able to cast the malignantly conventional spirit of Professor Bhaer from her, and to take her thrillers as seriously as her feminist editors and elucidators do today.”

. . . . . . . . . .

She raised her sister’s daughter for nine years

May Alcott Niereker, the youngest Alcott sister (loosely portrayed as Amy in Little Women), trained as an artist in Europe (subsidized by Louisa’s earnings). There she met a man, married, and had a daughter.

May died within a year of giving birth. Louisa earned the father’s family’s consent raise the child. Adopted at the age of two, the little girl was her Aunt Louisa’s namesake (and nicknamed Lulu).

Louisa herself never married nor had her own children, yet from all accounts, the nine years they spent together were happy ones. It was Louisa’s death that ended this lovely and unexpected journey into parenthood.

. . . . . . . . . .

Louisa may have had lupus or another autoimmune disease

Louisa was 55 years old when she died of a stroke in Boston in 1888, her death following just two days after her father’s. She’d long been in poor health, which she and others blamed on the mercury-laced medicine she took for the typhoid fever contracted while serving as a Civil War nurse.

However, modern scholars have had other theories for her chronic illness, which included headaches, skin rashes, vertigo, rheumatism, and other symptoms compatible with lupus or other autoimmune diseases.

. . . . . . . . . .

Leave a Reply