The Chosen Place, The Timeless People by Paule Marshall (1969)

By Lynne Weiss | On September 1, 2023 | Updated April 5, 2024 | Comments (0)

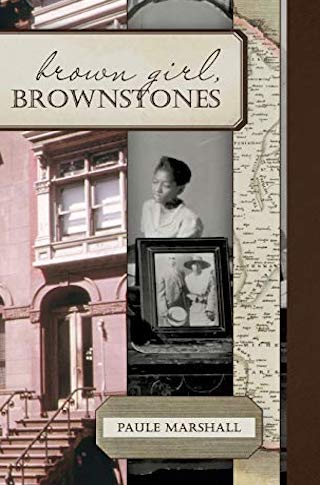

The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, was the second full-length novel by Paule Marshall (1929 – 2019). Following her first novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), she published a collection of four novellas in Soul Clap Hands and Sing (1961).

In its recognition of the intersectionality of race, class, and colonialism,The Chosen Place, The Timeless People was ahead of its time.

A New York Times reviewer called it “the best novel to be written by an American Black woman” when it was published in 1969. Such praise sounds patronizing in the present day, but let’s discount the reviewer’s limitations and focus on the recognition the comment represented.

Despite the many good reviews Marshall received, she never achieved the kind of celebrity afforded other Black writers, according to Donna Hill of the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College.

Marshall saw herself as the product of a triangular identity that included Africa, the Caribbean, and Brooklyn. The Chosen Place, the Timeless People thus appropriately revolves around three characters who come together on the fictional Caribbean island of Bourne “a hundred-and-seventy square miles of sugar cane stuck in the middle of nowhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Paule Marshall

(fair use image from BlackPast.org)

. . . . . . . . . .

Merle Kinbona

The first character we meet is Merle Kinbona (though we don’t learn her name right away). Kinbona is a native of Bourne who has a past in London and a future in East Africa. She is the fulcrum of the story. She is a powerful woman:

“… her eyes … gave the impression of being lighted from deep within (it was as if she had been endowed with her own small sun), and they were an unusually clear tawny shade of brown, an odd, even eerie, touch in a face that was the color of burnt sugar.”

In the course of the novel, we will learn that Merle is the daughter of a white British man, descended from the founder of the sugar plantation, and a Black West Indian woman who was murdered when Merle was a toddler.

Merle is headed toward middle age, but she dresses “like a much younger woman.” She wears “strange but beautiful earrings that had been given to her years ago in England by the woman who had been, some said, her benefactress; others, her lover.”

Along with the beautiful and finely made earrings, she wears numerous bracelets, “crudely made.” The contrast between these items, along with other aspects of Merle’s appearance, reveals Merle’s “diversity and disunity within herself” and that she has suffered “some profound and frightening loss.”

Saul Amron and Harriet Shippen

Even as we meet Merle, who is having car trouble due to the poor condition of the roads on the island, a small plane carrying four passengers is about to land and upend life within this community.

The passengers include the other two major characters of the novel: Saul Amron, an American anthropologist and a Jew, along with Harriet Shippen, his wife of one year, a mainline Philadelphia WASP whose family profited from the slave trade.

Saul is on his way to the island to undertake a research project that he hopes will help alleviate the extreme poverty of Bournehills, the community on the island where Merle and most of the other characters live. Harriet has influenced the foundation that is funding the project to bankroll Saul’s efforts.

Minor but Important Characters

We are introduced to Saul and Harriet through the eyes of another passenger on that plane, Saul’s statistician, Allen Fuso. A white American whose working-class background is very different from Harriet’s wealthy upbringing, he is the product of “the whole of Europe from Ireland to Italy.” Fuso, a closeted gay man, plays an important supporting role in the story.

The fourth passenger on the plane is Vere (Vereson Walkes). His tragic story is crucial to our understanding of Bournehills. He is a native of Bourne who is returning to the island after three years in the Farm Labor Scheme in the United States.

While working in the cane fields of Florida, Vere faced brutality and humiliation. Now he fantasizes about winning love and respect by building a race car and impressing everyone with its beauty and speed at the races on Whitsun.

Whitsun, a shortened form of White Sunday, is a Christian holiday that is widely observed in Britain and many of its former colonies with races, parades, and festivals. It occurs seven weeks after Easter Sunday. It is called White Sunday because traditionally people wore white clothing on that day, but Marshall is obviously drawing on another meaning of “white” in her emphasis on the festival in this novel.

We meet other characters through Vere: Leesy is the old aunt who raised Vere after his mother died in childbirth. Leesy lost her husband in a sugar-processing plant accident, and she has some prophetic powers, at least when it comes to Vere. She anticipates his return even though he has not been able to communicate his coming to her.

Another character we learn about through Vere is the (unnamed) woman who bore his child—a child who died of apparent neglect—and who now survives through prostitution.

Another significant, though minor, character is Lyle Hutson, the successful and popular barrister. Hutson is also a businessman. He is building a yacht club for successful Black people on the island such as himself who are barred from the Bourne Island Yacht Club because of their color.

Lyle is known for his adulterous affairs with white women. And he will be the friction that blocks Saul’s progress—and the instigator of Harriet’s tragic end.

. . . . . . . . . .

See Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones

. . . . . . . . . .

The World of Bournehills

All these characters, and many others, are fully delineated and brought to life through Marshall’s skillful prose. Each has her or his aspirations and motives; each has her or his sources of pain and disappointment.

In the unfolding of the story, we will learn that Merle’s ex-husband left her after learning of her affair with the white British woman who gave her those beautiful earrings. When he left, he took their daughter.

Saul is wracked with guilt over the death of his first wife, who died while they were doing anthropological field research in Honduras. Harriet, the least sympathetic of the three principals, is portrayed as a well-meaning though misguided white woman.

She is desperate to take on meaningful work despite an upbringing that raised her to exist purely as an ornamental accessory. But her belief that she knows best for all concerned, including those of a different culture, alienates Saul and places her in peril.

Saul is portrayed extremely sympathetically (though the repeated references to the size and shape of his nose suggest certain anti-Semitic tropes). His Jewish heritage is central to his identity, and the title of the novel evokes the idea of the chosen people. Saul, as a white American, had privileges not available to the Black people of Bournehills, and yet Bournehills is his chosen place.

Marshall offers parallels in the ancient histories and experiences of oppression of Africans and Jews. Like Africans, Jews have an ancient history. Both are arguably timeless in their traditions and awareness of the past.

The history and spirit of Cuffee Ned, leader of a briefly successful slave uprising, haunts the island and is mentioned again and again as well as re-enacted. Merle, in fact, loses her position as a teacher because of her insistence on relating the tale of Cuffee Ned to her students. (Marshall might have been anticipating the current situation in many U.S. schools.)

The scourge of sugar—widely regarded as the source of the slave trade in the Americas—hangs over the island as well. The working conditions are brutal. The workers are at the mercy of those who own the land and the processing equipment. And everyone on the island is diabetic.

Needless to say, the arrival of the American research team disrupts the balance of power in the Bournehills community. While the status quo was neither just or idyllic, the disruptions highlight the ongoing effects of British imperialism as well as the more recent imposition of U.S. capitalism.

Accusations of Homophobia

In her 2019 LitHub essay “Mourning Paule Marshall, the Foremother Who Didn’t Always Love Me Back,” Rosamond S. King, a self-described “queer Caribbean writer and critic,” tackles the issue of Marshall’s attitude toward queer love and identities.

There are certainly negative descriptions of gay people: early in the novel, when Merle takes Saul to the club known as Sugar’s, she indicates “that bunch out on the balcony” and says that no boy “over the age of three is safe” from them.

Yet closeted Allen is portrayed sympathetically, if sadly. He denies his sexual attraction to Vere until he finds himself unable to respond to the young woman Vere provides to him. It’s only when he realizes that he can reach orgasm only by masturbating to the sound of Vere having sex with a woman in the next room that he is able to recognize his own sexual identity.

Merle is filled with self-hatred as a result of her lesbian affair with the unnamed wealthy British woman in London. Yet I want to argue that while Marshall may not have always been the most enlightened writer regarding queer characters (in her LitHub essay, King traces an evolution in Marshall’s attitude in later novels), one can argue that at least part of Merle’s self-hatred might arise from the fact that her affair led her to lose access to her daughter after her husband left her.

Further, her unnamed lover was white and wealthy, and thus able to manipulate her. There are indeed no healthy and egalitarian same-sex relationships in this novel, but one might say the same about heterosexual relationships.

A Healing Connection

There is one exception to my statement above. While many of the characters come to a tragic end, Merle and Saul find a sexual connection that heals. To be sure, this is no happily-ever-after story. Yet these two are able to share an intimacy that is not just physical, but emotional as well.

They recognize that in the world in which they live, a relationship between the two of them is impossible, yet as a result of their connection they both come to understand what it is they must do next.

Saul is finished with fieldwork. The program to address poverty in Bournehills will continue, though in diminished form and without Saul. He hopes to go back to Stanford to “recruit and train young social scientists from overseas … that’s the best way: to have people … carry out their own development programs.”

Merle is bound for Africa, to find her daughter, even though she doesn’t know whether her former husband will “chase [her] from his door.” But she knows as well that she will eventually return to Bournehills.

“A person can run for years but sooner or later he has to take a stand in the place which for better or worse, he calls home,” she says, “and do what he can to change things there.”

It’s very much a conclusion and a recognition for our times—a time in which so many of us recognize that the work of change has to begin at the local level and with full recognition of and respect for the diversity that surrounds us.

But the conclusion of the novel takes me back to the story of Allen. He is the one who drives first Merle and then Saul to the airstrip so they can embark on the next stage of their respective lives. Allen has decided to stay behind on the island after they leave, for reasons that are not clear to Saul or Merle.

But we have seen Allen struggling with his own past—his upbringing of small-minded conformity—following the death of Vere and Allen’s recognition of his love for him. One senses that although he remains on the island, Allen will embark on his own quite profound and possibly joyous journey without ever leaving Bourne.

We might even think of those men out on the balcony who Merle points out to Saul near the beginning of the novel. Merle described them in negative terms, but Allen may see them differently. He may see in them the possibility of embracing his true identity and achieving an acceptance he has never had.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside of Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

See also: Inspiration from Classic Caribbean Women Writers.

Leave a Reply