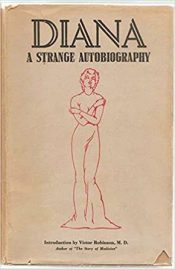

Diana: A Strange Autobiography by Diana Frederics (1939)

By Francis Booth | On March 17, 2021 | Updated August 13, 2023 | Comments (0)

Frances V. Rummell, an American writer and educator, published Diana: A Strange Autobiography (1939) under the pseudonym Diana Frederics. More of an autobiographical novel than an actual memoir, nonetheless draws upon the author’s life. The story details the title heroine’s discovery of her lesbian sexuality.

Positive portrayal of lesbians was considered shocking when the book was published. It’s now considered groundbreaking as one of the first works of gay fiction to have a happy outcome.

Published squarely between The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928) and the lesbian pulp novels that emerged in the early 1950s, Diana is a worthy, yet often overlooked addition to the genre. This analysis and appreciation is excerpted from Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission:

“This is the unusual and compelling story of Diana, a tantalizingly beautiful woman who sought love in the strange by-paths of Lesbos. Fearless and outspoken, it dares to reveal that hidden world where perfumed caresses and half-whispered endearments constitute the forbidden fruits in a Garden of Eden where men are never accepted.”

This was the blurb for the 1952 paperback edition – republished right at the beginning of the lesbian pulp fiction movement – of Diana: A Strange Autobiography by the pseudonymous Diana Frederics, who kept her identity secret until it was finally revealed on a PBS documentary in 2010.

Long after her death, it was revealed that the author was Frances V Rummell (1907-1969), a teacher of French at Stevens College, a women-only college in Columbia, Missouri (the second-oldest college in America to have remained all-female).

Diana was originally published by Dial Press in 1939 and republished in hardback by City Press of New York in 1948. Both editions contained an introduction by the sexologist Victor Robinson, explaining that lesbianism was:

“… Ancient in the days of Sappho of Lesbos. Yet such is our immunity to information, that when Havelock Ellis collected his various studies on Sexual Inversion (1897), he states that before his first cases were published, not a single British case, unconnected with the asylum or the prison, had ever been recorded.”

Robinson added: “I welcome any book which adds to the understanding of the lesbians in our midst. Among these books, I definitely place the present autobiography.” Unlike Dusty Answer and The Well of Loneliness, both the introduction and the main text use the word “lesbian,” quite astonishing for 1939; it would not be used in a published novel again for years.

Although it purports to be an autobiography and may well reflect the author’s own experiences, Diana is structured much like a novel. It is similar in many ways to Dusty Answer and to Vin Packer’s Spring Fire. Here also the heroine is unsure of her sexuality until she falls in love with a girl at college, but unlike Judith in Dusty Answer she does not subsequently try to revert to heterosexuality and end up alone and miserable.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . . . .

A typical tomboy

Diana has always been a tomboy: “I had always played with boys instead of girls, and growing older made no difference; I still did. Girls frankly bored me … I was scarcely conscious of being a girl. The boys accepted me as one of them as tacitly as I assumed that position.” No one, not even her parents, considers her to be a problem, she is just a regular tomboy to them.

“My mother and father had always taken my antics as they came, hopeful that time and age would season my tomboyish nature. Of course, they were indulgent with me; I was their only girl. I was a healthy young animal, full of energy and devilry, and tomboys were common enough. They mature into just as feminine young women as did the little girls who preferred dolls to BB guns.”

Like Carson McCullers’ tomboy Frankie Addams, Diana is very musical; her mother is not sure that her daughter should be attending music theory classes with boys but the music teacher convinces her to let Diana go; he says rightly that age and gender have nothing to do with musical ability, though by the time she is in her senior year her teacher is telling her that her very ‘clean touch’ on the keyboard is “masculine.”

A brief flirtation with a boy

In these classes, as well at home, Diana, like many tomboys, is surrounded by boys – including her brothers and young men from the college who rent rooms in her house – from the age of twelve to sixteen, when she goes to college. All these boys are of course protective of her and she is of course not the slightest bit seductive or provocative but one day, when she is “a hopelessly naïve child of thirteen,” it becomes obvious to her that she is not just one of the boys.

“One boy, a newcomer to our home, called me into his room one rainy Sunday afternoon to admire some snapshots. I hesitated a moment, since I never entered the guest rooms, but, reluctant to appear rude, I went. Ignorant as I was, his intentions were too abrupt to be misunderstood.

I recall only my fury; in spite of my years, it was enough to upset a blundering collegian. Like many people who manage to keep their heads in a tight predicament, I suffered repercussions. For weeks afterward I felt the full impact of sordidness. Despite the sudden exit of the collegian from our home, with no more explanation to my mother on my part than on his, this scene remained indelible.

It is almost incredible to me now to recall the extent of the effects of this assault on my innocence. I was made too abruptly aware that life amounted to something more than front yard games and school and camp.

My would-be seducer had said something to me which made me think more than I had ever honestly thought in my young life. I even got out my dictionary to find out what he’d meant by saying I was ‘seductive-looking.’ What a disturbing thought to one who until that very moment was completely unconscious of her body, despite a maturing physique.

I spent days brooding over the fact that I had been born a girl. I didn’t want to grow up. I didn’t want to be ‘seductive -looking.’ I hated the expression, I hated the vague meaning. Oh, the horror of becoming an adult!

Shocked into the realization that I was growing up in spite of myself, I turned suddenly into an antisocial, introspective, melancholy bookworm. Life took on the proportions of a pitiless hoax. In the diary I kept at this time is entered, in the handwriting of a fourteen-year-old, such a penetrating observation as this: ‘It is cruel of parents to read fairy tales to children. The transition from the delicate fantasy of the fairy tale to real life is painful. Life bumps into children as they grow up.’”

This coming-of-age moment turns her against boys, “for no reason except that they were growing up too. And some of them wrote notes to me in school that seemed silly and embarrassed me.” Diana retreats into her reading and music, though she does attend the school prom with the older boy Gil, whom she allows to kiss her, but that is far as it goes.

Enter Ruth

Gil is swept aside when Ruth enters the school; Diana is smitten with her. ‘She was too thin and her mouth was too large, but she had lovely titian hair, worn in braids around her head, solemn blue eyes, and such a sweet smile that I wondered if anyone could possibly be as angelic as she seemed.’ Ruth and Diana, among others, are invited to a Christmas house party. “I knew I would contrive in every way possible to share a room with her.” She manages it.

“That night when we went to bed alone, tired and happy with the day, Ruth’s thoughtless intimacy and good-night embrace almost took my breath away. I had been surprised to feel curious sensations of longing the few times I had ever touched her, but I could never have imagined the exquisite thrill of feeling her body close to mine. Now I was amazed.

Then, before I knew it, I realized I wanted to caress her. Then I became terrified by a nameless something that froze my impulse. The pain of resisting was torture, but the touch of her hand holding mine against her side was so infinitely sweet that I tensed for fear my slightest movement would make her turn away from me. Long hours I lay awake after she had gone to sleep, scarcely daring to breathe for fear she might move, not daring to hope that I might kiss her lips without startling her …

I never spoke to Ruth of my feelings. Fear restrained me. I had enough sense of proportion to realize that what I felt was extraordinary. I was afraid she would not understand my affection. I did not understand myself.”

Grace: A lost opportunity

Diane later goes to college to study French, and meets Grace, with whom we are expecting her to have an affair; “I had been rather awed by her cool charm and by her oft-repeated refusals to go out on dates with the boys who invited her.”

They read Baudelaire and Verlaine together – very heavy, decadent stuff for two college girls at that time; Baudelaire, of course, wrote The Flowers of Evil, and Verlaine, one of his followers, was the lover of Rimbaud. “Suddenly, inspired no doubt by Verlaine, she began to talk about homosexuality. Obviously, she was trying to sound out my reactions to the subject, and my self-consciously evasive replies made me blush with embarrassment.”

Diana is unprepared for this line of questioning; “As it was, my confusion was my defense. Extremely sensitive, Grace interpreted my awkwardness for reluctance, and, humiliated for having ‘misunderstood,’ she left.”

Considering marriage … to a man?

Before things with Grace have a chance to go anywhere, Diane meets Carl, an older man, who falls in love with her and asks her to marry him. “My first feeling was one of dismay.” She is flattered but confused, thinking she must accept, but “I could not force myself suddenly to end the happiest friendship I had ever known” – with, presumably, Grace.

Nevertheless, when he gives her his fraternity pin and kisses her she feels a “pale emotion – the first I had ever felt for a man.” But even this pale shadow of a feeling is enough to make her feel that perhaps she is after all normal. “When I left him I ran to my room giddily happy. Oh, dear God, it had happened. It was going to be all right.”

But then, the thought of having to have physical sex with Carl enters her head. “I have every possible reason but one to be convinced that Carl and I would be happily married – I did not know whether I loved him physically.” She has heard women talk and has read books on sexology which led her to believe that, even if she does not like having sex with him at first, she will come around. Diane tells Carl that she will live with him but not marry him. At first, all goes well.

“Some indescribable emotion pulled at me as I looked at him, and all I could think of was something I had read – of a woman happy that her lover need no longer sigh with unrest; she would give him ecstasy. I understood that now. Suddenly I gloried in an unexpected sense of possession. It seemed to me that I had never been so happy. There was no need to question. My place was with Carl.

It did not matter that first physical intimacy had been disappointing. I could not expect a miracle of chemistry to follow the mere act of defloration; I understood that it frequently took some little time for a woman to become adjusted, for her to learn rhythm, to grow together. At least I had managed the first pain. Now I could look forward.”

For some time, Diana feels as though she is becoming “normal,” though never in their time together had “physical intimacy meant anything to me but the giving of pleasure to Carl… the very words ‘desire,’ ‘passion,’ ‘ecstasy,’ were but fugitive words to me, symbols of unscented experience.”

Looking inward

Diana has become “a slave to dissimulation,” as she knows many married women are, whether or not they have lesbian tendencies.

When she goes to a women’s college in Massachusetts to take a Masters in German, the “number of lesbians I met there impressed me not only because my consciousness of them was sharpened, but because they were unmistakably frequent.” But even in this environment, she decides to hide her feelings: she learns “the grace of a lie and a new admiration for hypocrisy;” she vows that “no one would ever have such an easy clue to my own lesbianism.”

This self-imposed isolation of course makes her lonely. “I was approaching a future whose peculiar loneliness I could already understand.” What Diana cannot understand is what it would be like to indulge her preferences. “What was lesbian love like? Its intellectual pleasures were easy enough to guess at, but what physical pleasure did women achieve of one another… Vaguely I wondered how I would learn to know all the things I needed to know.”

Then she meets Elise and has her first physical experience with another woman. But Elise is already spoken for.

“I was released of all feeling, submerged in a glorious lethargy, timeless and in a dream. I could make no effort to open my eyes. I hadn’t expected it to be something like dying… I told her a little wildly that she had been my first; that she could not leave me, could not. Very gently she told me she had known, and that she had known all the while that Katherine was coming so soon. Now I knew why she had left me. For Elise that had been a gesture of fidelity – lesbian fidelity. I had made no difference.”

Diana reacts to these twin experiences – her first physical experience with a woman and her first emotional experience of betrayal – by leaving that night for Paris, wiser if not much older. “I realized that the incident with Elise had, for all its humiliation, given me a kind of assurance that I had needed desperately. Before Elise I had not known whether women could have sexual gratification of one another … Elise had completed my knowledge.”

Coming of age physically and emotionally

Diana has come of age physically and emotionally, and her next relationship, with Jane, is much more straightforward. “We wanted a normal domestic life and we wanted our happiness together. We asked nothing of anyone. We hurt no one. We were mature, free, and perfectly sure of ourselves.” Diana now realizes that to accept her “lesbianism and my circumstances without fear, without distaste, would be my ultimate freedom.”

Unfortunately, even though she is free within herself and she and Jane are free within their relationship, the outside world intrudes. After her first term teaching, her relationship with Jane is remarked upon and she is offered the choice between moving by herself into the single women’s accommodation or leaving the college. She chooses to leave. But Jane is not her final lover; she meets Leslie and leaves Jane – physically, though not emotionally, until the end of the book, when Leslie finally replaces Jane.

“I knew that Jane had been swept into time, into the forgotten. Even the thought of her seemed obscure. Leslie and I extricated ourselves; no longer need there be anything at all to remind us of Jane. I could feel how it had happened, but I could not have foreseen it. Slowly, half-prayerful, half-exultant, it had come to me – the testimony of her patience was enough – I could turn toward Leslie and know that her loyalty was no less than my own.”

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply