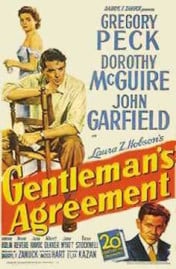

Gentleman’s Agreement (the 1947 film)

By Taylor Jasmine | On September 13, 2017 | Updated December 18, 2022 | Comments (0)

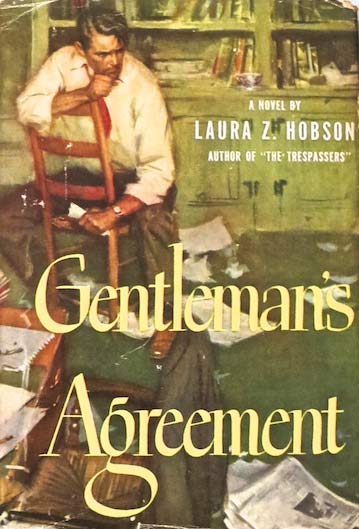

Gentleman’s Agreement, the classic 1947 film, was based on the novel of the same name by Laura Z. Hobson, who doubted any publisher would want to take it on, let alone that it would become an award-winning film.

It’s the story of Philip Schuyler Green, a journalist who poses as a Jew in order to investigate anti-Semitism in post-World War II New York City and environs.

Though it showed only a narrow slice of “upper crust” anti-Semitism, the film sensitively explores the topic and is quite true to the book.

Gentleman’s Agreement won Best Picture of 1947, with its director, Elia Kazan, getting the award for Best Director. Gregory Peck won for Best Actor, Dorothy Maguire for Best Actress. Though the film seems tame by today’s standards, it smashed Hollywood taboos by dealing with the topic of anti-Semitism.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Laura Z. Hobson, author of Gentleman’s Agreement

. . . . . . . . . .

Antisemitism in the U.S. seventy years later

Seventy years later, in 2017, a march by neo-Nazis and white supremacists in Charlottesville, VA brought to light that Antisemitism is still alive in America.

Though this fascist march was certainly not the first of its kind in the U.S., nor likely the last, it became a flashpoint because a counter-protester was murdered, and because the so-called President could not, would not, say the right words to denounce the hate-filled cowards marching with their cheap tiki torches chanting “Jews will not replace us!”

Gentleman’s Agreement — both the film and the book — might at first seem like period pieces. The story examines, through a set of appealing characters, the relatively genteel Antisemitism that Jews of a certain class faced in the aftermath of World War II in New York City and its suburbs.

But because of recent events, the book and film prove themselves still (unfortunately) relevant; and thought-provoking in the subtle, elegant ways of the literature and film-making styles of the mid-twentieth century.

. . . . . . . . . .

Review of Gentleman’s Agreement

(1947 novel by Laura Z. Hobson)

. . . . . . . . . .

Reflections on Gentleman’s Agreement

Here’s an excerpt from a piece titled “Reflections on Gentleman’s Agreement” by Ben Tousman in the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, April 1947, published shortly after the film was released:

Gentleman’s Agreement is a thoughtful, direct approach to the normal prejudices which lodge in the minds of many persons … it leaves a profound impression that hate need not be violent to be dangerous.

It exposes the prejudices of the “nice people,” the people who, as the film expresses it, “despise Senator John Rankin and Gerald L.K. Smith, who sit back and feel sick when little sly remarks about Jews go around the dinner table.”

Its central character is a “nice” wholesome girl, Kathy, played by Dorothy Maguire. She works hard at being tolerant and understanding, yet in the back of her mind is the persistent thought that its is not essentially wrong for “our kind” to exclude the “other kind.”

The ever-present question: “What can I do?”

Kathy’s suburban-type American loveliness and charming, finishing-school manners area a far cry from the brutish coarseness of the “little” Nazis. Yet, when pinned down for an explanation, their answers and hers are ominously alike: “I am only a little person. What can I do?”

“What can I do?” therefore becomes the central theme of the film. David Goldman (played by John Garfield) shows that the “nice” people who enter “gentleman’s agreements” to exclude others must perform more than lip service to the idea of democracy; they must act positively, as Kathy finally does, to carry out the liberal ideas they spout so readily.

. . . . . . . . . .

How Gentleman’s Agreement Smashed Hollywood Taboos

. . . . . . . . . .

Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Phil Green

Phil Green, the grim, tenacious magazine writer played effectively by Gregory Peck, reveals the truth that the fight against prejudice must be waged not only against the actively evil but the inactively good — that the sweet, wholesome Kathies, unless shocked out of their complacency, can be used effectively by the Gerald L.K. Smiths.

Interesting sidelights in the picture are the way some Jews view the problem. There is the stenographer who changes her name and denies her Jewishness; she adopts a lordly attitude toward the “other kind” of Jews, thereby revealing a strong Jewish self-hatred.

Then there is the industrialist who prefers not to stir up the problem. And the scientist who no longer cares for religion as such, yet flaunts his Jewishness in protest against pressures of the outside world.

A straightforward view of Antisemitism

Gentleman’s Agreement is a straightforward presentation that is convincing because of its essential honesty. It pulls no punches and brings the question of anti-Semitism to those people whose insight is most needed — the decent, middle-class, average Americans who profess belief in democracy, yet fail to practice it.

Hollywood has shown courage in producing Gentleman’s Agreement. It is to be hoped that more of the same type will be produced in the future — pictures that not only deal with anti-Semitism, but with racism and other great social problems of this country. (—Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, April 1947)

. . . . . . . . . .

Leave a Reply