8 Poems by Rosario Castellanos on Life, Culture, and Religion

By Skyler Gomez | On October 28, 2019 | Updated May 1, 2025 | Comments (5)

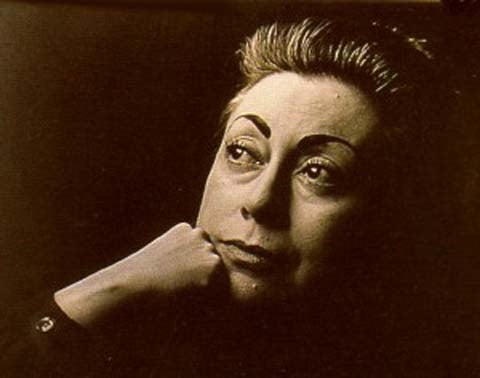

Rosario Castellanos (born Rosario Castellanos Figueroa, 1925 – 1974), author, poet, and diplomat, was one of Mexico’s most influential literary voices of the twentieth century. Presented here are eight poems by Rosario Castellanos in both in their original Spanish (poemas de Rosario Castellanos) and in English translation, exploring, among other themes, her views on religion and critique of cultural constraints.

Castellanos’ work dealt with issues of culture and gender in her home country, and went on to become a significant influence on contemporary Mexican feminist theory and cultural studies.

After losing both parents in 1948, Castellanos was left to fend for herself. This tragic event along with the poem Endless Death by José Gorostiza marked the start of her career as a writer and cultural critic. Soon after, she enrolled in UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) to study law, philosophy, and literature.

Here are some resources for analyses of Rosario Castellano’s poetic works:

- Rosario Castellano was one of Mexico’s greatest poets

- Feminize Your Canon: Rosario Castellanos

- Considering the “Nocturne” and the Importance of Poet Rosario Castellanos

Themes in Rosario Castellanos’ poetry

Castellanos’ poetry is deeply Catholic. She admired the work of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the Mexican nun-poet of the seventeenth century, and Saint Teresa of Ávila, the Spanish sixteenth-century religious activist and author.

Her poetry expresses social injustices and admiration for the creator of nature and is considered both powerful and authentic. Identity and the spirit of her home state of Chiapas are themes of her poetry, and she wrote of the women’s rights movement in Mexico.

The Paris Reviews article mentioned above writes of her work: “Images of literal and emotional solitude haunt the work of Rosario Castellanos, the visionary Mexican feminist, poet, novelist, and essayist. It’s a state she both cherished and mourned. From a young age, the act of writing was her bulwark against the pain of loneliness.”

The poems are presented here:

- Charla / Talk

- Tres Poemas / Three Poems

- Telenovela / Soap Opera

- Nacimiento / Birth

- Amor / Love

- Apelación al solitario / Appeal to the Solitary One

- Pasaporte / Passport

- Epitafio del hipócrita / Epitaph of a Hypocrite

. . . . . . . . .

Charla (Talk)

…porque la realidad es reducible

a los ultímos signos

y se pronuncia en s6lo una palabra …

Sonríe el otro y bebe de su vaso.

Mira pasar las nubes altas del mediodía

y se siente asediado (bugambilia, jazmín,

rosal, dalias, geranios,

flores que en cada pétalo van diciendo una sílaba

de color y fragancia)

por un jardín de idioma inagotable.

Talk

…because reality is reducible,

ultimately, to signs,

and is pronounced in only one word …

The other smiles and sips from a glass.

Watches the passage of tall midday clouds

and feels bothered (bougainvillea, jasmine,

roses, dahlias, geraniums,

flowers of which each petal is speaking a syllable

of color and fragrance)

by a garden of inexhaustible language.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rosario Castellanos

. . . . . . . . . .

Tres Poemas (Three Poems)

I.

¿Qué, hay más débil que un dios? Gime hambriento y husmea

la sangre de la víctima

y come sacrificios y busca las entrañas

de lo creado, para hundir en ellas

sus cien dientes rapaces.

(Un dios. 0 ciertos hombres que tienen un destino.)

Cada día amanece

y el mundo es nuevamente devorado.

II.

Los ojos del gran pez nunca se cierran.

No duerme. Siempre mira (¿a quién?, ¿a dónde?),

en su universo claro y sin sonido.

Alguna vez su corazón, que late

tan cerca de una espina, dice: quiero.

Y el gran pez, que devora

y pesa y tiñe el agua con su ira

y se mueve con nervios de relámpago,

nada puede, ni aun cerrar los ojos.

Y más allá de los cristales, mira.

III.

Ay, la nube que quiere ser la flecha del cielo

o la aureola de Dios 0 el puño del relámpago.

Y a cada aire su forma cambia y se desvanece

y cada viento arrastra su rumbo y 10 extravía.

Deshilachado harapo, vellón sucio,

sin entraña, sin fuerza, nada, nube.

Three Poems

I.

What is more feeble than a god? It wails, starving,

smelling the blood of a victim,

eats sacrifices and hunts for the entrails

of the created, in order to sink its hundred

rapacious teeth into them.

(A god. Or certain men who have a destiny).

Each day dawns

and the world is once again devoured.

II.

The eyes of the great fish never close.

It does not sleep. It always watches (where? for whom?)

in its bright and soundless universe.

Some time its heart, beating

so close to the spine, says: I want.

And the great fish, which devours

and weighs heavily, tinges the water with its rage

and moves with nerves of lightning,

can do nothing, not even close its eyes.

And beyond the crystals, watches.

III.

Oh, the cloud that wants to be an arrow in the sky

or the halo of God,

or a shaft of lightning.

And at each draft its form changes and it disappears;

each wind blows to its own direction and misleads it.

Frayed rag, dirty fleece

without substance, without force, nothing, cloud.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Telenovela (Soap Opera)

El sitio que dejó, vacante Homero,

el centro que ocupaba Scherezada

(o antes de la invención del lenguaje, el lugar

en que se congregaba la gente de la tribu

para escuchar al fuego)

ahora está ocupado por la Gran Caja Idiota

Los hermanos olvidan sus rencillas

y fraternizan en el rnismo sofá; señora y sierva

declaran abolidas diferencias de clase

y ahora son algo más que iguales: cómplices.

La muchacha abandona

el balcón que Ie sirve de vitrina

para exhibir disponibilidades

y hasta el padre renuncia a la partida

de dominó y pospone

los otros vergonzantes merodeos nocturnos.

Porque aquí, en la pantalla, una enfermera

se enfrenta con la esposa frívola del doctor

y Ie dicta una cátedra

en que habla de moral profesional

y las interferencias de la vida privada.

Porque una viuda cose hasta perder la vista

para costear el baile de su hija quinceañera

que se avergüenza de ella y de su sacrificio

y la hace figurar como a una criada.

Porque una novia espera al que se fue;

porque una intrigante urde mentiras;

porque se falsifica un testamento;

porque una soltera da un mal paso

y no acierta a ocultar las consecuencias.

Pero también porque la debutante

ahuyenta a todos con su mal aliento.

Porque la lavandera entona una aleluya

en loor del poderoso detergente.

Porque el amor está garantizado

por un desodorante

y una marca especial de cigarrillos

y hay que brindar por el con alguna bebida que nos hace felices y distintos.

Y hay que comprar, comprar, comprar, comprar.

Porque compra es sinómino de orgasmo,

porque compra es igual que beatitud,

porque el que compra se hace semejante a los dioses.

No hay en ella herejía.

Porque en la concepción y en la creación del hombre

se usó como elemento la carencia.

Se hizo de é1 un ser menesteroso,

una criatura a la que Ie hace falta

lo grande y lo pequeño.

Y el secreta teológico, el murmullo

murmurado al oído del poeta,

la discusión del aula del filósofo

es ahora potestad del publicista.

Como dijimos antes no hay nada malo en ello.

Se está siguiendo un orden natural

y recurriendo a su canal idóneo.

Cuando el programa acaba

la reunión se disvuelve.

Cada uno va a su cuarto

mascullando un–apenas–“buenas noches”.

Y duerme. Y tiene hermosos sueños prefabricados.

Soap Opera

The space which Homer permitted vacant,

the center which Scheherezade occupied

(or before the invention of language, the place

where the people of the tribe came together

to listen to the fire)

is now occupied by the Grand Idiot Box.

Brothers forget their arguments

and fraternize on the same sofa; mistress and servant

declare class differences abolished

and now they are something more than equals: accomplices.

The girl abandons

the balcony which serves as a showcase

for exhibiting her resources

and the father renounces the game

of dominoes and postpones

other shameful nocturnal snoopings.

Because here, on the screen, a patient

comes face to face with the frivolous doctor’s wife

and lectures her

speaking of professional ethics

and interferences in private life.

Because a widow sews until she has lost her sight

in order to pay for her daughter’s quinceñera

a daughter who is embarrassed by her and her sacrifice

and makes her look like a servant.

Because a girlfriend waits for one who has gone;

because an intriguer plots deceptions;

because a testimony is falsified;

because a spinster takes a bad step

and does not succeed in hiding the consequences.

But also because the debutante

frightens all with her bad breath.

Because the washerwoman intones a hallelujah

in praise of a powerful detergent.

Because love is guaranteed

by a deodorant

and a special brand of cigarettes

and there’s a toast for it with some drink

which makes us happy and distinct.

And there must be buying, buying, buying, buying.

Because buying is synonymous with orgasm,

because purchasing is equal to beatitude,

because he who buys is made similar to gods.

There is no heresy in it.

Because in the conception and the creation of man

deficiency was used as an ingredient.

He was made a needy being,

a creature who lacks

the significant and the small.

And the theological secret, the murmur

whispered in the hearing of the poet,

the classroom discussion of the philosopher,

is now authority of the publicist.

As we said before there is nothing bad in it.

It’s following a natural order

and is turning to its suitable channel.

When the program ends

the gathering dissolves.

Each one returns to his quarters

mumbling–scarcely–a “good night.”

And each sleeps. And has splendid prefabricated dreams.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Nacimiento (Birth)

Estuvo aquí. Ninguno (y él menos que ninguno)

supo quién era, cémo, por qué, adónde.

Decía las palabras que los otros entienden

–las suyas no llegó a escucharlas nunca–;

se escondía en el lugar en que los otros buscan,

en su casa, en su cuerpo, en sus edades,

y sin embargo ausente siempre y mudo.

Como todos fue dueño de su vida

una hora o más y luego abrió las manos.

Entonces preguntaron: ¿era hermoso?

Ya nadie recordaba aquella superficie

que la luz disputó por alumbrar

y Ie fue arrebatada tantas veces.

Le inventaron acciones, intenciones. Y tuvo

una historia, un destino, un epitafio.

Y fue, por fin, un hombre.

Birth

He was here. No one (and he the least of all)

knew who he was, how, why, where.

He spoke words which others understood

–his own he never could hear–

he hid himself in the very place where others searched,

in his house, in his body, in his ages,

ever still absent and mute.

Like all he was master of his own life

an hour or more, and then he opened his hands.

Then they asked: was he beautiful?

Almost no one remembered such a surface,

which struggled with light for illumination

and was snatched back so many times.

They invented for him actions, intentions. And he had

a history, a destiny, an epitaph.

And he was, at last, a man.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Amor (Love)

Sólo la voz, la piel, la superficie

pulida de las cosas.

Basta. No quiere más la oreja, que su cuenco

rebalsaría y la mano ya no alcanza

a tocar más allá.

Distraída, resbala, acariciando

y lentamente sabe del contorno.

Se retira saciada,

sin advertir el ulular inútil

de la cautividad de las entrañas

ni el ímpetu del cuajo de la sangre

que embiste la compuerta del borbotón, ni el nudo

ya para siempre ciego del sollozo.

El que se va se lleva su memoria,

su modo de ser río, de ser aire,

de ser adiós y nunca.

Hasta que un día otro lo para, lo detiene

y lo reduce a voz, a piel, a superficie

ofrecida, entregada, mientras dentro de sí

la oculta soledad aguarda y tiembla.

Love

Only voice, skin, the polished

surface of things.

Enough. The ear does not want more, for its hollow

may overflow and the hand can no longer reach

very far to touch.

Absentminded, it slides, caressing,

and slowly knows the contour.

It retires satisfied

without noticing the futile howl of a heart in captivity

nor the congealing impetus of the blood

which assaults the bubbling floodgate, nor the forever blind knot of a sob.

He who leaves carries his memory,

his way of being river, of being air

of being farewell and never.

Until one day another stops him, delays him

and reduces him to voice, skin, to a surface

offered, surrendered, while inside himself

the hidden solitude waits and trembles.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Apelación al solitario (Appeal to the Solitary One)

Es necesario, a veces, encontrar compañía.

Amigo, no es posible ni nacer ni morir

sin con otro. Es bueno

que la amistad Ie quite

al trabajo esa cara de castigo

y a la alegría ese aire ilícito de robo.

¿Cómo podrías estar solo a la hora

completa, en que las cosas y til hablan y hablan,

hasta el amanecer?

Appeal to the Solitary One

It’s necessary, at times, to find company.

My friend, it’s not possible to be born or to die

without another. It’s good

that friendship removes

from work the appearance of punishment

and from happiness the illicit air of theft.

How could you be alone at that complete

hour, in which you talk and talk with things

until the dawn?

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Pasaporte (Passport)

¿Mujer de ideas? No, nunca he tenido una.

Jamás repetí otras (por pudor o por fallas nemotécnicas)

¿Mujer de acción? Tampoco.

Basta mirar la talla de mis pies y mis manos.

Mujer, pues, de palabra. No, de palabra no.

Pero si de palabras,

muchas, contradictorias, ay, insignificantes,

sonido puro, vacuo cernido de arabescos,

juego de salón, chisme, espuma, olvido.

Pero si es necesaria una definición

para el papel de identidad, apunte

que soy mujer de buenas intenciones

y que he pavimentado

un camino directo y fácil al infierno.

Passport

Woman of ideas? No, I’ve never had one.

I never repeated others (out of modesty or faulty memory).

Woman of action? No, not that either.

It’s enough to look at the shape of my feet and hands.

Woman, well, of word. No, not of word.

But, yes, of words–

many, contradictory, oh, insignificant,

pure sound, sifted empty of arabesques,

a salon game, gossip, foam, oblivion.

But if a definition is necessary

for the identification card, note

that I am a woman of good intentions,

and that I have paved

a direct and simple route to hell.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Epitafio del hipócrita (Epitaph of a Hypocrite)

Quería y no quería.

Quería con su piel y con sus uñas,

con lo que cambia y cae; negaba con ‘sus vísceras,

con lo que de sus vísceras no era aserrín, con todo

lo que latía y sangraba en sus entrañas.

Quería ser él y el otro.

Siamés partido a la mitad, buscaba

la columna de hueso para asirse, colgar

su cartilaginosa consistencia de hiedra.

Mesón desocupado,

actor, daba hospedaje al agonista.

Gesticulaba viendo su sombra en las paredes,

deglutía palabras sin sabor, eructaba

resonando en su vasta oquedad de tambor.

Ensayaba ademanes

–heroico, noble, prócer–

para que al desbordarse la lava del elogio

lo cubriera cuajando después en una estatua.

No a solas inunca a solas!

dijo el brindis final,

alzó la copa amarga de cicuta.

(Mas no bebió su muerte sino la del espejo).

Epitaph of a Hypocrite

He wanted and he did not want.

He wanted with his skin and with his nails,

with that which changes and falls; he denied with his guts, with all of his gut

that was not sawdust, with all

that throbbed and bled in his entrails!

He wanted to be him and another.

Siamese twins parted in the middle, he searched

the column of bone to seize it, to hang

his cartilage like the consistency of ivy.

Empty inn,

an actor, he gave lodging to the agonized.

He gestured, watching his shadow on the walls,

swallowed words without flavor, belched

resounding in his vast drum hollow.

He tested gestures

–heroic, noble, illustrious–

so as to be overcome by the lava of praise

covering him, congealing afterward into a statue.

Not alone, never alone!

He said the final toast,

raised the bitter glass of hemlock.

(But he did not drink his death, rather that of the mirror).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

I absolutely loved exploring the poems of Rosario Castellanos! Her unique voice and perspective on gender and identity really resonate with me. I appreciate how you highlighted the depth and nuance in her work. It’s inspiring to see how her legacy continues to influence modern literature. Thank you for sharing these insights!

Me da mucho gusto que hayas presentado aquí a esta excelente autora mexicana, que no solo escribió poesía, sino también teatro, ensayos, cuentos, novelas (Balún Canan, Oficio de Tinieblas).

De la traducción, solo encontré las siguientes inexactitudes: Charla es Talk (like in table talk); the fish has bones, only one spine; And, In Love: El que se va se lleva su memoria… is rather: He who leaves…

Pero para mí, traductora y poeta mexicana, es muy importante que se conozca a Rosario Castellanos y se aprecie su obra. Gracias, Skyler Isabella.

Irene, Gracias for this (I’m just at the beginning of learning Spanish), and I’ll convey your thanks to Skyler Isabella Gomez, who worked so diligently to add Latina authors to the site. I see that you have some corrections to the translations, and I will try to figure them out!

I think I got two of your three corrections … Charla and He who leaves … but I couldn’t figure out where to put “the fish has bones only one spine.” Can you help me out with where exactly that should go and in which poem? Thank you!

That line should start : “so close to a bone”.

Thanks for taking this into account.