The Tenth Muse: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

By Elodie Barnes | On October 13, 2022 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (1)

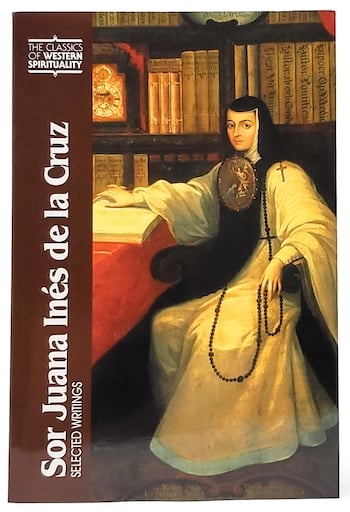

Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillana (November 1648 (?) – April 17, 1695), more familiarly known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a Mexican writer, poet, philosopher, composer, and Hieronymite nun.

Known as the “Tenth Muse” or as “The Phoenix of America” due to her formidable achievements in literature and scholarship, she is now revered as an early feminist.

Her writing is the subject of vibrant academic discourse on subjects as wide-ranging as women’s rights, environmentalism, colonialism, and education.

Early years

The exact date of Sor Juana’s birth is unknown; however, most accounts place her birth in November 1648, with her baptism not taking place until December 1651.

She was born out of wedlock to a Creole mother, Doña Isabel Ramírez de Santillana, and a Spanish father, Pedro Manuel de Asbaje. The family — her mother, grandparents, four sisters, and a brother, with her father mostly absent — lived in relative comfort on a hacienda in San Miguel Nepantla, near Mexico City.

Juana’s intellectual pursuits began at an early age. Some accounts claim that she learned to read at the age of three, when she hid in the hacienda chapel with her grandfather’s books from the adjoining library.

While stories of her reading and writing Latin by age four, and Greek by age eight, are probably exaggerated, there is no doubt that she was formidably intelligent.

At the age of sixteen, she was sent to live in Mexico City with her maternal aunt. She begged her mother to allow her to disguise herself as a boy, to gain entrance to Mexico City University which was then open only to men. Her mother refused, and Juana continued her studies in private.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Life at Court

Juana’s intelligence and beauty attracted the attention of the viceroy, Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marqués de Mancera, and the vicereine, Doña Leonor Carreto. In 1664 she was invited to court as a lady in waiting.

The system that she navigated during this time was complex. Mexico was a highly autocratic society, and the University, the Court, and the Church were the most powerful institutions in the country.

The Court represented the point of contact with Europe and European culture, while the Church controlled the dissemination of knowledge and culture. It was a man’s world, run by men for men, and this makes Sor Juana’s achievements, in the precarious feminine space that she made for herself between these institutions, even more astounding.

She was much admired for her literary accomplishments, especially after the Marqués “tested” her in a meeting of several prominent theologians, philosophers, and poets, all of whom were astonished by her intelligence, and she received several offers of marriage, all of which she declined.

In the biography Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith (1982) Octavio Paz wrote of the impact this repressive patriarchal system had on Sor Juana’s writing:

“Her work tells us something, but to understand that something we must realize that it is utterance surrounded by silence: the silence of the things that cannot be said. The things she cannot say are determined by the invisible presence of her dread readers [those clergy who read and disagreed with her work] … An understanding of Sor Juana’s work must include an understanding of the prohibitions her work confronts …”

Religious life and secular writing

In 1667, with a “total disinclination to marriage” and a desire to have “no fixed occupation which might curtail my freedom to study,” Juana began her life as a nun, first in the austere convent of San José de las Carmelitas Descalzas and then, from 1669, in the more lenient Convent of Saint Paula of the Order of San Jerónimo.

Here the nuns had their own living quarters, complete with kitchens, bathrooms, and parlors, and often their own servants too. Sor Juana was allowed to study, correspond with other scholars, compose music that was both secular and religious, and hold an intellectual salon in her quarters each week.

In the convent, where she remained until her death, Sor Juana amassed one of the largest private libraries on the continent (around 4,000 volumes), together with an enviable collection of scientific and musical instruments.

She continued to be supported by powerful figures, and when the new viceroy, the Marqués de la Laguna, arrived in 1680, both he and his wife visited Sor Juana and supported the publication of her works in Spain. Under their patronage, she became the unofficial court poet and wrote plays, poetry, religious services, and for state festivals.

In her poetry, she employed the full range of forms and themes of the time, including sonnets, romances, and ballads, and drew on a vast range of Classical, mythological, religious, and philosophical sources of inspiration.

Her lyrics were moral and satirical as well as religious, and she also wrote dramatic, scholarly, and comedic works. Her output was prolific, and she wrote fluently in three languages: Spanish, Latin, and Nahuatl.

Many of Sor Juana’s secular poems were love poems, written in the first person as a woman narrator, and preoccupied not with the romance of love but the disillusionment, pain, and jealousy that accompany it.

She acknowledged feeling en dos partes dividida (divided into two parts), torn between reason and passion, devotion and sensuality.

There has been much debate over the nature of her friendship with the Marqués’s wife, María Luisa. The only real clues lie in Sor Juana’s poetry. Poems dedicated to Lisi or Lysis extol her virtues — which would have been traditional and expected for a court poet — but some also seem to allude to a romantic relationship, or at least the desire for one:

My divine Lysis:

do forgive my daring,

if so I address you,

unworthy though I am to be known as yours.”

. . . . . . . . .

Sor Juana on Academy of American Poets

. . . . . . . . .

Feminism, controversy, and Respuesta a Sor Filotea

Sor Juana achieved great fame in both Mexico and Spain, but with renown came disapproval from church officials. In the early 1680s, she broke with her Jesuit confessor, Antonio Núñez de Miranda, writing to him in 1681:

“The cause of your anger…has been none other than the ability that God has given me in creating these wretched verses without asking permission from Your Reverence.”

She also lost the protection of the Marqués and marquise de la Laguna after they departed for Spain in 1688.

She was always an outspoken supporter of women’s rights, in particular women’s rights to education, and often used her work to criticize the patriarchal system that rendered women all but invisible.

One of her best-known poems, “Hombres necios” (Foolish Men) fiercely accuses men of the same behavior that they criticize in women:

You foolish men who lay

the guilt on women,

not seeing you’re the cause

of the very thing you blame…

Their favor and disdain

you hold in equals state,

if they mistreat, you complain,

you mock if they treat you well…

Famously, Sor Juana paraphrased St. Teresa of Ávila in saying that “One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper.”

In response, several high-ranking Catholic officials, including the Archbishop of Mexico, publicly condemned her “waywardness.” In November 1690 the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, published — without Sor Juana’s permission — her critique of a 40-year-old sermon by António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit preacher.

Fernández de Santa Cruz, using the female pseudonym Sister Filotea, added his own letter to this Carta Atenagórica, in which he criticized Sor Juana for not focusing on religious studies. While he conceded that some of her critical points were valid, he maintained that as a woman she should give up writing and devote herself to prayer instead.

Sor Juana responded in March 1691, in the famous Respuesta a Sor Filotea. In it, she defended the right of women to education and knowledge and traced the many obstacles she had faced throughout her life in her pursuit of learning, including her self-inflicted punishments for learning too slowly:

“It turned out that the hair grew quickly and I learned slowly. As a result, I cut off the hair in punishment for my head’s ignorance, for it didn’t seem right to me that a head so naked of knowledge should be dressed up with hair, for knowledge is a more desirable adornment.”

She stated that the study of “human arts and sciences” were necessary for an understanding of sacred theology and underscored her devotion to the pursuit of learning.

The pressure of censorship

Besieged by criticism and under great pressure from her confessor, Sor Juana stopped writing. Whether this was a process of forced abjuration, or whether she simply chose to stop writing to avoid further censure, is unclear.

There is a document of repentance dated March 1694, in which she agreed to undergo penance, and she supposedly voiced her regret at “having lived so long without religion in a religious community.”

Sor Juana’s library and collections were sold for alms, and she renewed her religious vows. She died in April 1695 while nursing her fellow sisters during a plague epidemic.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Legacy of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Although Sor Juana’s work was largely ignored for centuries after her death, the 1980s saw new translations appear, inspired by a growing feminist movement, and a ground-breaking biography written by Octavio Paz.

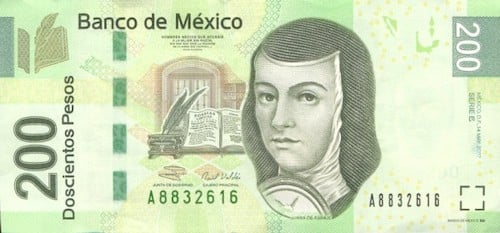

Sor Juana is now considered an icon of Mexico and Mexican identity: her name was inscribed on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress in 1995, her image has been printed on the 200 peso note, and her former cloister is a center for higher education.

It was her relationship with María Luisa which has fascinated filmmakers and writers the most. The 1999 novel Sor Juana’s Second Dream, by poet and scholar Alicia Gaspar de Alba, portrays the friendship as homoerotic, and became the basis for the play The Nun and the Countess by Odalys Nanín. It also inspired an opera, Juana, which premiered at the University of California Los Angeles.

More recently, interest in Sor Juana and María Luisa has been sparked by the 2016 television series Juana Inés, which was first produced in Mexico and is now available on Netflix.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Selected Works, edited by Julia Alvarez,

translated by Edith Grossman (W.W. Norton, 2016) - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Feminist Reconstruction of Biography and Text,

by Teresa A. Yugar (Wipf & Stock, 2014) - Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith, by Octavio Paz

(no longer in print but available in English translation)

More about Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

See more author biographies on this site.

I just recently finished a research paper on Sor Juana. She was a fascinating woman. I’d sure like to give Bishop Santa Cruz a piece of my mind for betraying her, someone he called a “friend.” And don’t get me started on Núñez or Archbishop Aquila. What a pair!! I’m so glad that Sor Juana’s work is getting noticed again. She is a wonder!!