The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton (1905) – a review

By Taylor Jasmine | On December 11, 2016 | Updated May 18, 2023 | Comments (0)

The House of Mirth was the first novel by Edith Wharton. Her first book of stories, The Greater Inclination, was published in 1899. Published in 1905, The House of Mirth is the story of Lily Bart, an ambitious woman of New York City’s high society at the turn of the twentieth century.

Lily Bart is well-bred but has no money, and at age twenty-nine, is closing in on permanent spinsterhood. In those times, that was nothing less than tragic. The story is of her downward spiral over the course of about two years.

Her troubling decline was seen as a commentary on a corrupt and heartless upper class.

About The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth was an instant bestseller, much to Wharton’s surprise, as up to that time, she felt quite insecure about her ability to write and was worried that she wouldn’t be taken seriously.

She exulted to her publisher Charles Scribner, “It is a very beautiful thought that 80,000 people should want to read The House of Mirth, and if the number should ascend to 100,000 I fear my pleasure would exceed the bounds of decency.”

How delighted she would be if the word reached her in the Great Beyond, that The House of Mirth is still in print, as is Ethan Frome, The Age of Innocence, The Custom of the Country, as well many of her other titles.

The House of Mirth did indeed establish her reputation, as described in the 1997 Simon & Schuster edition:

A literary sensation when it was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1905, The House of Mirth quickly established Edith Wharton as the most important American woman of letters in the twentieth century.

The first America novel to provide a devastatingly accurate portrait of New York’s aristocracy, it is the story of the beautiful and beguiling Lily Bart and her ill-fated attempt to rise to the heights of a heartless society in which, ultimately, she has no part.

From the staid conventionality of Old New York to the forced conviviality of the French Riviera, from the drawing foom of Gus Trenor’s Bellomont to the dreary resort of a downtown boardinghouses, Wharton created her “first full-scale survey,” as her biographer R.W.B. Lewis put it, “of the comedie humaine, American style.”

A brilliantly satiric yet sensitive exploration of manners and morality, The House of Mirth marked Wharton’s transformation from an amateur into a professional writer on par with her contemporary and friend Henry James. It figures among her most important works.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (1920)

. . . . . . . . . .

In Edith Wharton: A Woman in Her Time (1971) Louis Auchincloss wrote of the novel’s significance to her emerging reputation:

“The House of Mirth … marks Edith’s coming of age as a writer. She had at last the perfect subject: fashionable New York. ‘The it was before me,’ she wrote, ‘in all its flatness and futility, asking to be dealt with as the theme most available to my hand, since I had been steeped in it from infancy.’

Her only doubt was whether she could extract from a study of irresponsible pleasure seekers any significance deeper than the pleasure which they sought, but her doubt was resolved with the realization that she could find dramatic significance in society’s power of debasing people and ideals.”

A 1905 review of The House of Mirth

From the original review in The New York Times, December 30, 1905: Rarely has any book aroused such universal interest or provoked such illuminating discussions as has The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton.

What a human grip also has on our sympathy, and what a complex creature is Lily Bart, with her demi-monde longing for luxury, and her fine capacity for conscience.

Many consider her no better than Becky Sharp, and only attribute her refusal to sell herself to a careless disregard for consequences, while others find in her the true nobility of soul, whose many ignoble actions are due to force (or is it lack?) of circumstances beyond her control. Her final spiritual rejuvenation (and here there is no division of opinion) is due to the influence of her love for Belden.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Spoiler alert— the fate of Lily Bart

As to her committing suicide, this is also open to question. Did she, after finding Belden’s love grown cold, and after learning that “if you have no money, you needn’t come round,” deliberately take a big enough dose to end it all, or did she merely increase the dose to induce more sleep?

She mentions running a risk, but there is no conclusive proof that she really meant to do so, and after reading such a painful story, it seems too bad that she was not allowed to “live happily ever after” as a reward for her virtue.

The other persons in The House of Mirth notwithstanding Mr. Newport, are living, breathing creatures and represent a certain portion (not all, thank goodness) of “high society.” It is too bad they don’t realize their responsibility a little more clearly and lead a better example to “the masses who ignorantly worship them.”

Revealing the foibles of the rich

With the moral searchlight turned upon them, Mrs. Wharton reveals the voluntary conditions of the “very rich” as a far greater crying shame than the involuntary condition of the poor, who do not regard respectability as a bore of a disgrace.

One final word of praise for Mrs. Wharton’s refinement of touch: Any German or French author, in dealing with such delicate situations as Lily’s scene with Trevor, or even Dorset, would have made them common or risqué. But not so Mrs. Wharton; in the entire book there is not one scene or word we could wish recalled.

. . . . . . . . . .

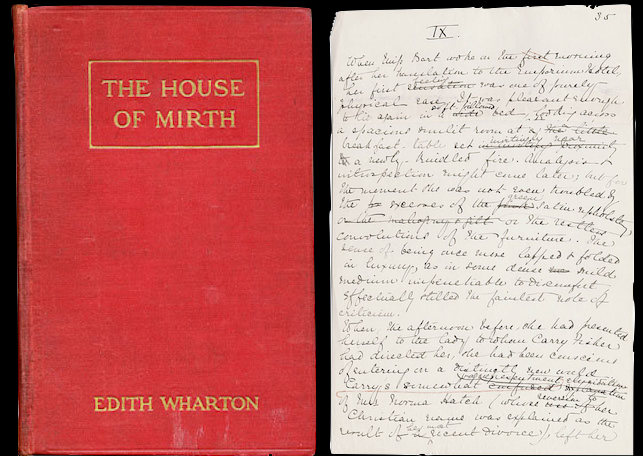

Original 1905 cover; and a manuscript page

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The House of Mirth

“She had no tolerance for scenes which were not of her own making.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Half the trouble in life is caused by pretending there isn’t any.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I was just a screw or cog in the great machine I called life, and when I dropped out of it I found I was of no use anywhere else.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Everything about her was warm and soft and scented; even the stains of her grief became her as raindrops do the beaten rose.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Her whole being dilated in an atmosphere of luxury. It was the background she required, the only climate she could breathe in.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She was so evidently the victim of the civilization which had produced her, that the links of her bracelet seemed like manacles chaining her to her fate.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“We are expected to be pretty and well-dressed until we drop.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Don’t you ever mind,” she asked suddenly, “not being rich enough to buy all the books you want?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“No insect hangs its nest on threads as frail as those which will sustain the weight of human vanity.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Little as she was addicted to solitude, there had come to be moments when it seemed a welcome escape from the empty noises of her life.”

More about The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Read full text on Project Gutenberg

- Listen to The House of Mirth on Librivox

- 2000 film adaptation

Leave a Reply