Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade

By Lynne Weiss | On April 16, 2021 | Updated February 21, 2025 | Comments (0)

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade (2020) sheds new light on fascinating female literary figures of twentieth century and their sojourns in the Bloomsbury district of London the interwar years. First, a brief description from the publisher:

“In the pivotal era between the two world wars, the lives of five remarkable women intertwined at this one address: modernist poet H. D., detective novelist Dorothy L. Sayers, classicist Jane Harrison, economic historian Eileen Power, and author and publisher Virginia Woolf. In an era when women’s freedoms were fast expanding, they each sought a space where they could live, love, and—above all—work independently.

With sparkling insight and a novelistic style, Francesca Wade sheds new light on a group of artists and thinkers whose pioneering work would enrich the possibilities of women’s lives for generations to come.”

The following review was contributed by Lynne Weiss:

I visited London for the first time in the fall of 1991. Before my husband and I left, I read that the hotel we had booked in Bloomsbury was on the former site of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press.

Hoping the building would offer literary inspiration, I was disappointed by the bland budget hotel that was our home for our week-long visit. I didn’t spend a lot of time puzzling over the discrepancy between my expectations and the reality—there were plenty of things to do in London beyond inhaling any imagined remnants of Virginia Woolf’s genius that might have lingered in the air.

I recalled that drab hotel in the course of reading Francesca Wade’s excellent Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars (Random House, 2020). I knew about the Blitz, but not the extent of its destruction.

As Wade makes clear, the combination of bombs and the growth of educational institutions means that the Bloomsbury of today is architecturally very different from what it was between 1916 – 1940, the period covered in Wade’s book.

Does it matter? I consider this question for my own community (a city founded in 1630, old for an American city). Today it faces a severe housing shortage and thus an ongoing debate on how to provide housing while preserving history.

I’m a sucker for wandering about in my hometown as well as elsewhere, reading historic plaques and trying to piece together the connections between the buildings and streets around me and the lives of those who came before.

London is a paradise for that kind of ambling. The city has more than 950 blue plaques marking the locations of people and events significant to the city’s history, as well as hundreds of other historical markers.

“Personally, we should be willing to read one volume about every street in the City, and should still ask for more,” Virginia Woolf declared. Francesca Wade has set out to create one of those volumes, focusing on the women who lived in a particular square over the course of a couple of decades.

But why Bloomsbury, and why Mecklenburgh Square? Bloomsbury was a neighborhood for people “either going up or going down,” according to novelist Margery Allingham. For women longing for independence and freedom from social expectations, such as H.D (Hilda Doolittle), Dorothy L. Sayers, Jane Harrison, Eileen Power, and Virginia Woolf, it was a neighborhood of possibilities.

And yet, Mecklenburgh Square, the focus of Wade’s book, has only a single blue plaque marking the former residence of one of the five (H.D.) whose achievements and contributions Wade profiles in this enlightening book.

The five lived in Mecklenburgh Square at separate times, yet they shared a determination to realize their potential as writers and intellectuals. It was a time when the barriers to such achievement were just beginning to fall. Only in 1918 did property-owning women over the age of thirty win suffrage in Britain. (It was finally extended to all women over twenty-one in 1928). And in 1919, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act allowed women to serve as lawyers and civil servants and to receive university degrees.

But changes to laws do not ensure equality of opportunity. The 1919 law did not require that women in the civil service receive the same pay as men performing the same jobs, for example— and they did not.

Educational opportunities for women remained segregated and limited. And the women profiled in this book endured pain of a personal nature, made worse by the prevailing devaluing of women’s experiences—H.D. was reviled after suffering a still birth for taking a hospital bed that she was told should have gone to a soldier; Sayers spent her life hiding the existence of a son born to her out of wedlock; Harrison endured the humiliation of being rebuffed by a male colleague who regarded her as a mother; Power was embarrassed by unwanted marriage proposals.

. . . . . . . . .

H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

. . . . . . . . .

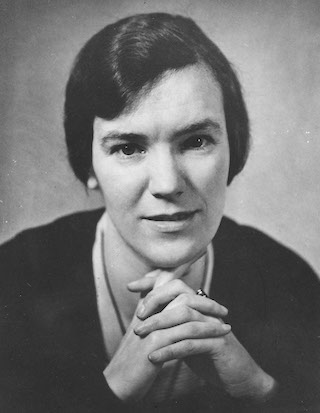

H.D.

Wade’s story of the square is bookended by wars, beginning in 1916, when Germany sent huge Zeppelin airships, like something out of science fiction, to drop incendiary bombs on London. In February of that year, H.D. (the pen name of poet Hilda Doolittle)., recently championed by her high school beau Ezra Pound for her Imagist poetry, and her husband, Richard Aldington, moved into a first floor flat at 44 Mecklenburgh Square.

H.D. threw herself into her writing to manage her pain over marital troubles, composing “Eurydice,” the groundbreaking poetic monologue that marked her transition from an impersonal Imagist aesthetic to explorations the inner lives of mythological heroines. She eventually removed herself to Cornwall, which she experienced as a “cold healing mist,” and where she met Bryher, the woman whose money and devotion finally allowed H.D. to find the affirmation and freedom she needed to realize her artistic calling.

. . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Sayers

. . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Sayers

Fewer than three years after H.D. left Mecklenburgh Square, Dorothy Sayers, who just a few months earlier had been part of the University of Oxford’s first group of women graduates, moved into H.D.’s former flat. Sayers, then twenty-seven, had completed her studies in modern languages five years earlier, but women were not awarded degrees until 1920.

Despite the hostile atmosphere (one don insisted that women sit behind him so he wouldn’t have to see them as he lectured), Sayers enjoyed her time at Oxford, where she was known for riding a motorbike and dressing in trousers.

In 1920, London’s streets were filled with injured, shell-shocked, and homeless veterans. Yet for young Sayers, it offered possibility. She dreamed of becoming a poet, but determined to support herself through her writing, and drawn to gruesome stories, she created the character of Lord Peter Wimsey, the fictional detective at the center of what would become her best-selling novels.

While living in Mecklenburgh Square, she spent her Saturdays in the nearby British Museum reading about sensational trials and wrote her first novel (Whose Body?), which introduced readers to Wimsey.

. . . . . . . . .

Hope Mirrlees and Jane Ellen Harrison

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Harrison

Jane Harrison was seventy-five when she arrived at 11 Mecklenburgh Street. I knew little about Harrison, one of the first female academics in Britain, beyond her appearance in Woolf’s extended 1928 essay, A Room of One’s Own, as “a bent figure, formidable yet humble, with her great forehead and her shabby dress” and later in the essay as the author of books on Greek archaeology.

When Harrison moved to Mecklenburgh Street, she did so in the company of Hope Mirrlees, a much younger woman, whom Woolf described in her diaries as a “spoiled prodigy” but also as one who knew “Greek and Russian better than I do French.”

Harrison spent her last years on Mecklenburgh Street, dying there in April 1928, but they may have been her best years. There she was finally freed from the restrictions placed on her as a woman at Cambridge University, to live “alongside intellectuals and revolutionaries, still learning new languages and developing fresh ideas.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Eileen Power

. . . . . . . . . .

Eileen Power

The most surprising and delightful chapter of a book full of delightful surprises is Wade’s account of Eileen Power, someone who was completely unknown to me. Power moved into number 20 in January of 1922 and remained there through August 1940.

After receiving the “perfectly disgusting” news in 1920 that her alma mater, Cambridge, had decided not to grant women full membership in the university, Power accepted a post as a lecturer in economic history at the London School of Economics.

When she moved to Bloomsbury, she had recently returned from a year of traveling around the world as the recipient of a fellowship that allowed her to journey alone to Egypt, India, China, Japan, and North America—sometimes dressed as a man.

Her 1924 Medieval People was a surprise bestseller and pioneered portraying the lives of ordinary artisans, prioresses, and traders as contributors to history. Wade suggests that Woolf likely had Power’s work in mind when she called for “Anon” to be returned to her rightful place in history.

Throughout her life, Power was fascinated by China, which she had visited during her traveling fellowship and returned to in 1929. She became engaged to Reginald Johnston, former tutor to the 13-year-old Puyi, the last emperor of China. The marriage to Johnston never materialized, as Power’s professional commitments repeatedly took priority over domestic stability. She eventually married a much younger student.

. . . . . . . . . .

Virginia and Leonard Woolf

. . . . . . . . . .

Virginia and Leonard Woolf

Power’s final year in the square is marked by the arrival of Virginia and Leonard Woolf at 37 Mecklenburgh Square on August 17, 1939. Soon after, the N-zis invaded Poland and Britain declared war on Germany.

The Woolfs, who had learned that they were on a list of people marked for capture by the Gestapo following Germany’s anticipated invasion of Britain, planned to commit suicide in the event of Britain’s defeat, an event that seemed quite likely.

Despite these anxieties, Woolf completed a great deal of work during her year in Mecklenburgh Square, including a novel, Between the Acts, and a biography of art critic Roger Fry.

Her diary entries record a busy life of dinners, parties, writing commissions, and gardening. But on September 7, 1940, Germany began bombing London, and the Woolfs abandoned Mecklenburgh Square for their country house in Sussex. For the first time in her life, Virginia had no home in London.

London had been Woolf’s muse: “London itself perpetually attracts, stimulates, gives me a play & a story & a poem without any trouble, save that of moving my legs through the streets… To walk alone in London is the greatest rest.”

Bombs drove the Woolfs to Sussex. The Blitz drove the London School of Economics temporarily out of London as well, and Power followed it to Cambridge. Most of Mecklenburgh Square was destroyed in the war, but the statue of the Woman of Samaria, the only statue in London depicting a woman at the time these women lived, still stands at the entrance of Mecklenburgh Square.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Summing up

Francesca Wade has not only uncovered the history of women such as Harrison and Power, who had faded from memory, but adds dimension to figures such as H.D. and Sayers by informing readers of the complexities of their situations and the very real obstacles—personal and social—they overcame.

Square Haunting is a valiant, poignant, and highly readable effort to uncover that history and revive our memories of some of the notable women who worked to bring women’s creativity and thought to the forefront of history. Would that information have been more available to us if Mecklenburgh Square had not been bombed? Probably not. Bombs or no bombs, we need accounts such as Wade’s.

And yet those of us who wander the streets in search of literary or historical inspiration might better recognize it in the buildings where people actually lived and worked. As Lytton Strachey wrote upon Jane Harrison’s death: “What a wretched waste it seems that all that richness of experience and personality should be completely abolished! Why, one wonders, shouldn’t it have gone on and on?”

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, she has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Leave a Reply