Country Place by Ann Petry (1947)

By Nava Atlas | On April 25, 2015 | Updated September 23, 2022 | Comments (0)

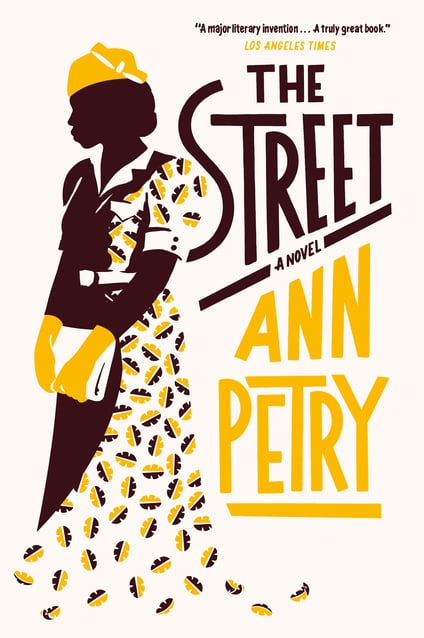

Country Place by Ann Petry (1947) came on the heels of the massive success of her first novel, The Street, published just the year before. The Street was groundbreaking, becoming the first novel by an African-American woman to sell more than a million copies. It would eventually sell more than a million and a half, and was reissued in a new edition in 1992.

Born Ann Lane, Ann Petry (1908 – 1997) was raised in Old Saybrook, Connecticut and was shielded from the very worse effects of racism in early 20th-century America. In 1938, she married George Petry, and the couple moved to Harlem. There she began a writing career in earnest, working as a journalist, columnist, and editor.

Hilary Holladay, in her concise biography Ann Petry (1996), introduces Country Place insightfully:

“In Country Place, Ann Petry explores the way in which people’s relationships determine the quality of their communal life, just as her other novels and stories do.

But this prompt follow-up to The Street has a decidedly abstract dimension to it. Although Country Place details the conflicts dividing classes, races, and genders, and makes use of the naturalistic techniques displayed in The Street, it is primarily concerned with relationships between creators and creations, real places and narrative spaces.

The novel has two primary points of focus: the implicitly contentious relationship between the first-person narrator, a pharmacist called Doc Fraser, and an unnamed, omniscient narrator and the explicitly contentious relationship between Doc and his nemesis, a gossipy taxi driver known as the ‘Weasel.’

The novel’s preoccupation with narrative control provides an intriguing analog to its complicated plot. Country Place reveals that storytelling and truth-telling go hand in hand, even when they seems to be at war.

Like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather before her, Ann Petry invokes a male narrator as a means of establishing credibility while simultaneously infusing her tale with irony.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about The Street (1946)

. . . . . . . . . . .

An entry into “raceless” writing?

In a thorough academic analysis by Emily Bernard, she situates Country Place in a unique place in American literature. In “Raceless” Writing and Difference: Ann Petry’s Country Place and the African-American Literary Canon, she observes:

“Country Place is a quintessential novel of the ‘raceless’ writing genre whose excision from the African-American literary canon is as meaningful as the novel itself. A thorough examination of Country Place reveals that, indeed, race does move meaningfully in the story, and suggests that the same might be true for other ‘raceless’ novels.

Ann Petry represents white characters in order to destabilize conventional assumptions about whiteness and universality; to complicate stereotypes about white versus black systems of morality; and to create a racially progressive vision about the transformation of modern life in a small town in post World War II America.”

For an in-depth view of Country Place placed in a broader context, we highly recommend you head over to read the rest of this lengthy analysis titled “‘Raceless’ Writing and Difference: Ann Petry’s Country Place and the African-American Literary Canon.”

Country Place would not achieve the blockbuster sales of The Street, and it wasn’t as enthusiastically received. Still, it was a solid entry into the canon of a talented American author. Following is a typical review, published shortly after its publication.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ann Petry

Photo: Carl van Vechten

. . . . . . . . . . .

A 1947 review of Country Place by Ann Petry

From the original review in Corsicana Daily Sun, TX, October, 1947: Country Place by Ann Petry tells the story of Johnny Roane, married to Glory a year before the war. He spends four years in he army and comes home with his heart aching for love of his wife.

A much less patient person, she could not endure a heart ache for that length of time. Living with Johnny’s parents, earning a meager living at Perkins’ store, she had been gallivanting around town while her husband gallivanted around the world, and just as Johnny becomes available once more, she decides she prefers Ed Barrell, who has been serving as husbands’ alternate for a number of consolable war widows.

Glory, after all, has only been following in her mother’s footsteps. Johnny’s mother suspects that where there’s smoke, there’s fire. Weasel the taxi driver knows there’s fire and does his best to spread around the smell of smoke.

It’s a story, in short, of vice and corruption in a small Connecticut town. Mrs. Petry brings in some fortuitous melodrama to cap it all, but up to the end she has not made returned soldier, seducer, faithless wife real enough.

Unhappily the great passion which served to place her first novel, The Street (among the most memorable pieces of fiction of 1946) is missing; happily there is nothing here to make us change our minds about her ability to write.

Leave a Reply