Ann Petry, Author of The Street

By Nava Atlas | On October 16, 2018 | Updated July 30, 2024 | Comments (0)

Ann Petry (October 12, 1908 – April 28, 1997) was the first Black woman to produce a book (The Street, 1946) whose sales topped one million. Ultimately it would sell a million and a half copies.

Encounters with the pervasive racism that permeated American life in their time were relatively rare — though not entirely absent — in the relatively sheltered life that Ann and her siblings experienced.

The daughter of practical, professional parents

Born Ann Lane, she was raised in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. A fourth-generation native of Connecticut, Ann was the daughter of practical, ambitious parents. Her father, Peter Clark Lane, was a pharmacist; her mother, Bertha James Lane, was a podiatrist. For other role models she had an extended family of strong professional women.

Though a high school teacher encouraged her to write, Ann went to pharmacy college and received a degree. This was in the early 1930s, when a practical profession was a blessing during the Great Depression. She followed in her father’s footsteps to become a pharmacist in the family drugstore.

Ann was always an avid reader who was particularly taken with Louisa May Alcott’s fictional heroine Jo March as a role model for her writerly aspirations.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Marriage and a move to Harlem

In 1938, she married George Petry, and the couple moved to Harlem. There she began a writing career in earnest, working as a journalist, columnist, and editor. She took writing courses at Columbia University and drawing and painting courses at Harlem Art Center.

She also participated in Harlem’s American Negro Theatre, performing onstage as Tillie Petunia in Abram Hill’s play On Striver’s Row.

Ann was active in social issues as well. She ran an after school program at an elementary school in Harlem, and was an organizer for Negro Women Inc.

These experiences opened Ann’s eyes to the challenges facing working class women, whose lives were far more vulnerable than what she had experienced in her own upbringing. Witnessing class, race, and economic struggles firsthand was what informed her fiction.

Ann wrote many short stories for magazines and journals and periodicals, but it was “On Saturday, the Sirens at Noon” — a story that was published in a 1943 issue of The Crisis that proved a major turning point.

She received a notification after the story appeared encouraging her to enter the competition for the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship. She submitted the first few chapters ofThe Street and was awarded the fellowship, which came with a handsome cash award.

. . . . . . . . . .

See more about The Street (1946)

. . . . . . . . . .

The Street: An overnight sensation

The Street was published in 1946, and became an overnight sensation. The New York Times called it “a skillfully written and forceful first novel.’’ Its significance was as a novel that explored Black women’s experience through the intersection of race, gender, and class.

Despite its commercial and overall critical success, The Street was not without its detractors. Some Black critics, including James W. Ivey of The Crisis, objected to Petry’s one-sided portrayal of Harlem as a “seething cesspool of sluts, pimps, juvenile delinquents …” and deemed it “worthless as a picture of Harlem though interesting as a revelation of Mrs. Petry.”

Ann Petry published seven other books, including children’s books, but none was as successful as The Street. She was uncomfortable with fame. In a 2019 appreciation of her work, Parul Segah wrote in the New York Times:

“Petry experienced celebrity as a kind of spiritual theft. ‘My soul was no longer my own,’ she recalled to the Times in 1992. ‘I was a Black woman at a point in time when being a writer was not usual, and I was besieged. Everyone wanted a part of me.”

She fled Harlem for her hometown in Connecticut, where she lived until her death, at 88, in 1997.

The threat of exposure still loomed, and she destroyed her letters and other pieces of writing, and remained ambivalent whenever her work was reissued: ‘I feel as though I were a helpless creature impaled on a dissecting table — for public viewing,’ she wrote in her journal.”

Opining on the race issue

Upon publication of The Street, Ann was compelled, whether willingly or reluctantly, to comment on the ongoing American race issue. Here is one such interview fromThe Harrisburg Telegraph, March, 1946:

“The answer to the race question is going to be found in the children, if you ask me,” says Ann Petry, whose first novel, The Street, just published, won the Houghton Mifflin $1,500 award.

The opinions of most adults are formed and set; but the children are different. We hear a lot about the changing reaction of the white to the Negro. The average person never stops to think that there is a reaction of the Negro as well …

You have to convert on all sides. How can you expect good will unless the Negro gets a chance to know white people and know what they are like? As it is now he does not know them.

But if children mixed more in schools, the two races would know each other. They would learn, while they are young, that in both races there are human beings — those who are kind, those who are cruel, those who are intelligent, those who are dumb. In short that the other race is made up of human beings.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo by Carl Van Vechten

. . . . . . . . . .

Pointed reflections on Black America

Ann Petry’s life was less fraught than that of the characters she wrote about. She was sensitive to the oppression and disadvantages caused by racial bias, and these themes were reflected in her fiction.

In an essay, Ann said of her work: “When I write for children, I write about survivors. When I write for adults, I write about the walking wounded.”Ann Petry by Hilary Holladay (1996), encapsulates what she sought to express as a writer of fiction:

“Ann Petry’s fiction deals with prejudices of race, sex, and class, and with the ways in which the American dream of success and plentitude haunts, and finally mocks, those people who fail to achieve it. She writes in rhythmic, deceptively simple prose, frequently underscoring the unsettled, disrupted nature of human relations via setting and environmental detail.

Petry calls her characters “the walking wounded” and her use of naturalism, especially in The Street and Country Place, provides them with realistically portrayed, yet fundamentally unstable, ground on which to make their hobbling way. In 1950, Petry suggested why people want to read fiction that addresses difficult social issues:

Possibly the reading public, and here I include myself, is like the man who kept butting his head against a stone wall and when asked for an explanation said that he went in for this strange practice because it felt so good when he stopped.

Perhaps there is a streak of masochism in all of us; or perhaps we feel guilty because of the shortcomings of society and our sense of guilt is partially assuaged when we are accused, in the printed pages of a novel, of having done those things that we ought not to have done — and of having left undone those things we ought to have done.

Because racism and sexism and their consequences remain integral to life in America, Petry’s characterizations of these prejudices in her fiction continue to inspire feelings of masochisms and guilt.

Although she did the bulk of her writing midcentury, her novels and stories articulate the same pain and outrage expressed by contemporary chroniclers of sexism and racism.

Petry’s works are thus more timeless — and timely — than one might like them to be. Petry herself has said of The Street, “It just saddens my heart so that if you added crack, it would be the same story today. It’s just so painful and frightening.”

The Street: reissued in 1992

In 1992, The Street was re-released by its original publisher, Houghton Mifflin. Ann Petry fame rose once again, now age 84. She was profiled in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and other publications.The Street was recognized as an important contribution to Black American literature.

The Hartford Courant, a newspaper relatively close to Ann’s home of Old Saybrook, Connecticut home, quoted Margo Perkins, a teacher of African American literature at Trinity College on the impact of The Street:

“It is one of the first novels to talk about Black women’s experience in terms of the intersection of race, class and gender, and it paralleled Richard Wright’s work, which very much focused on Black men. It has been reclaimed in the last several years as a very important novel.”

Reviewing the 1992 edition of The Street, the L.A. Times review remarked:

“Lutie Johnson is an incandescent spirit trapped in circumstances that constantly conspire to douse her potential. White women view her as a threat and men of every race appraise her as a possible conquest.

Whenever she allows herself to be naive enough to forget the rules of the game — that is, that an impoverished Black woman alone is considered prey — she is violently reminded of her situation.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: 6 Interesting Facts About Ann Petry

. . . . . . . . . .

Teaching and continuing to write

Sudden fame after The Street’s success proved overwhelming. Petry and her husband left New York City to return to Old Saybrook, purchased a house, and raised their only daughter there. The town where she was grew up remained her home base for the rest of her days, even as she taught and lectured far and wide.

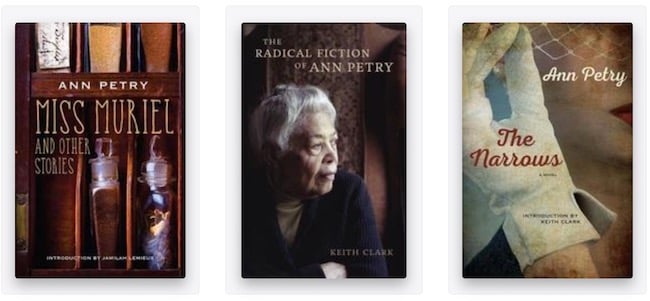

The Street was quickly followed in 1947 withCountry Place, a story taking place in the familiar setting of a drugstore. The Narrows (1953) is a novel of an interracial romance.

After this, a few children’s books were produced:The Drugstore Cat(1949), Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad (1955), and Tituba of Salem Village (1963).

She continued to write short stories and even went to Hollywood for a brief sojourn to work on a movie script. Petry published The Narrows in 1953, and finally, a short story collection, Miss Muriel and Other Stories, in 1971.

The later years of Ann Petry

Though none of her subsequent works sold in the sheer volume of The Street, nor achieved its notoriety, Ann Petry remained a respected voice, received a number of honorary degrees, and was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame.

Her work has lately begun to be revisited and studied. Ann Petry died in Old Saybrook in 1997, at the age of 89.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Ann Petry

On this site

Major Works (fiction)

- The Street (1946)

- Country Place (1947)

- The Narrows (1953)

- Miss Muriel and Other Stories (1971)

Other Works (for younger readers)

- Tituba of Salem Village

- Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad

- The Drugstore Cat (1948)

Biographies about Ann Petry

- The Radical Fiction of Ann Petry by Keith Clark (2013)

- At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry (2008)

More information

- Wikipedia

- Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame

- Meet Lutie Johnson on PBS’s American Masters

- Ann Petry: Brief Life of a Celebrity-Averse Novelist, Harvard Magazine, Jan./Feb. 2014

- Letters Illuminate Life of African American Novelist Ann Petry

- Tayari Jones: In Praise of Ann Petry

Leave a Reply