Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1925)

By Nava Atlas | On December 28, 2021 | Updated August 28, 2022 | Comments (0)

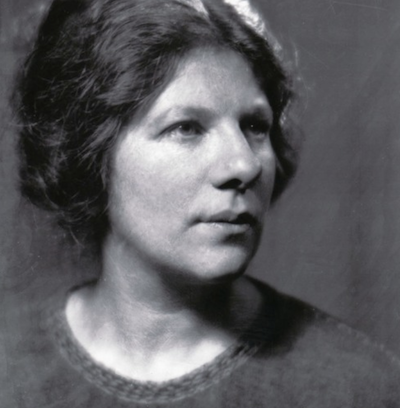

Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1880 – 1970) is the best-known novel by this immigrant writer whose work reflected the Jewish immigrant experience in America of the early 1900s. To set this kind of story down with a female perspective was a rarity in her time, reflecting the author’s chutzpah and determination.

At the age of ten, in 1890, Yezierska arrived with her family to New York City’s Lower East Side. A product of the immigration wave of the late 1800s, she never quite shed the feeling of being an outsider.

Longing to rise above her circumstances, she was somewhat hampered by her brittle personality and a measure of self-loathing. In her final book, the autobiographical Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950), she wrote: “With a sudden sense of clarity, I realized the battle I thought I was waging against the world had been against myself, against the Jew in me.”

Bread Givers, an autobiographical novel, delves into the well-trodden theme of an immigrant family whose children strain against Old World parents. The father, Reb. Smolinsky might be learned in the holy Torah, but he’s childish, impractical, and inflexible when it comes to his daughters. One 1925 reviewer described his character as “Dickensian.”

The three daughters chafe under their father’s domination. The youngest and feistiest is Sara, oddly nicknamed “Blut und Eisen” (Blood and Iron) from the time she is tiny. She rebels from the start, fighting for her autonomy, seeking self-determination. We can imagine that she is Anzia, through and through. The process of breaking away from her father’s domination is painful. Some of her strivings are awkward and uncomfortable, but she emerges as a person (mostly) in command of her world.

. . . . . . . . .

Anzia Yezierska on her struggle to write Bread Givers

Anzia Yezierska on her struggle to write Bread Givers

. . . . . . . . . .

Anzia Yezierska’s writing life in brief

Bread Givers bestowed a greater measure of success to Yezierska, who three years earlier had published the novel Salome of the Tenements. She wrote many fine short stories and even had a stint as a Hollywood writer. Hungry Hearts (1920), her first collection of short stories, was made into a successful 1922 silent film. Yezierska came to be known in Hollywood as “the Sweatshop Cinderella.” though she resented this rags-to-riches stereotype.

Long before her death in 1980, she all but disappeared from the literary world. The mid-1970s brought a wave of reconsiderations of her stories and novels. Bread Givers was reissued in 1975 and 2003, and some of her stories were anthologized, introducing them to new audiences.

In a 1925 essay in the Salt Lake Telegraph, Yezierska mused on what prompted her to write Bread Givers:

“I have always wondered why the people I know and lived with were never found in stories. Whatever I read of the poor were not my poor; not the life I had lived. They were dressed up in romance, in drama, in colorful climaxes that made fine literature …

The living people in their everyday working clothes with all the lines and wrinkles of work and worry were not there. The brutal fight over pennies at the pushcart, the cheap cafeterias where the hungry working girl goes for food only to come out hungrier after her meal than before; the terror of the poor on the first of the month when the rent has to be paid: these realities were too trivial, too sordid for stories.

And yet I knew that in this grinding waste of the dull everyday lay buried rich drama, more colorful than any false heroics of fiction. This conviction that the poorest life is rich enough for the greatest story, that the real struggle of the washerwoman, the shop girl, the fishwife, no matter how sordid, how ugly, throbs with dramatic beauty, is what goaded me to write.”

Despite occasional awkward and overwrought prose, Bread Givers is still eminently readable, and was highly praised upon its publication. In its 1925 review, the New York Times praised the novel for “enabling us to see our life more clearly, to test its values, to reckon up what it is that our aims and achievements may mean. It has a raw, uncontrollable poetry and a powerful, sweeping design.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

How I Found America by Anzia Yezierska

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1925 Review of Bread Givers

From the original review in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 5, 1925: When Anzia Yezierska wrote Salome Of the Tenements, all applauded. New York has a ghetto, a legendary yet pitifully and stubbornly real maze of dingy brick walls, where cobblestones make wagons rattle and trucks bounce; where every one of long rows of pushcarts has its screaming peddler and haggling customers; where streets are crowded and each fire escape has its ragged washline and show of bedding airing …

… Where basements are gloomy and attics are fetid and men and women and squalling children cling despairingly to traditions that are worn out even in the Old World. as they reach out eager hands for the milk and honey of the Promised Land. this America of ours.

It has been in this ghetto that the sociologist has written his books and quarreled with his brothers, jealous, as though the place belonged to him, and, because it did not suit his purpose, angry if anyone suggested the same sightless urge people for color and beauty was fermenting along with the disease and living blight, in the melting pot.

Anzia Yezierska, however. dared to find poetry, ideals, and even a measure of grimy contentment on Old Hester Street. The Russian immigrant Jew, to her, is a person and not a specimen for study.

Bread Givers, the latest Yezierska panorama of ghetto lives, published by Doubleday, Page & Co., has its human feeling, the divine comedy of the dreadful commonplace, and the glory of achievement, small to who inherited North America from our ancestors. but great to the family of circumstance reduced in Europe, poverty-stricken here and risen again from the basement by the second generation.

The ghetto has its flavor. Flavors being so much a matter of odor, he rest of New York City avoids its Lower East Side as much as possible. Stomachs that can stand herring and rye bread three times a day make it so. Yet Yezierska does not grow hysterical over these, her people. There is a saving sense of humor in Bread Givers.

The reader is looking at real people, living with them, suffering their little scandals, dreading the arrival of the rent lady, stuffing butter-less bread to ease the gnawing pangs of hunger, Papa shouting Hebraic invocations to Jehovah. while his daughters fight to keep him supplied with soup and the roof over his head.

Papa dabbles in his weak business ventures and his moments of religious elation while the landlady bangs at the door; selling his daughters to fine husbands—or at least. to any husbands—for the sake of his old age and sold out by his own bargaining—it would be sardonic if there were less feeling and filial affection woven into the tale.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Marrying off Bessie to the fish merchant, for instance, the fish merchant who was so carried away by his wrath that he threw dollars’ worth of change into a distracted woman’s face in a mutually greedy argument over the price of flounder. Papa, who chanted from the Torah and who worshiped Jeremiah, drove the bread from his mouth by breaking the hearts of his daughters and wearing out that stolid machine, his wife.

The naked simplicity of the poor which strips them of all inhibitory reserves and leaves them free to climb upward, since they cannot sink lower, comes to life in Bread Givers.

Anzia Yezierska does what Fannnie Hurst tries to do. One admired the expert craftsmanship of Lummox, but it was, after all, only a somber piece of storytelling. The rise of little “Blut und Eisen” (Blood and Iron) — what Papa calls Sara, his most stubborn, determined daughter, comes only from a deep suffering and a great experience.

Chanting the Torah did not pay the rent but it did drive Sara from her Papa. As the dean of her college told her, she was a pioneer. And she was an immigrant, escaping from the ghetto to the other side of town. There are many like her, all over. We do not always like their presence, but that is because we fail to understand them.

We have not taken into account the brave adventure they set out upon, uprooting themselves from the tenements and pushing painfully into a new land of sunshine, grass, and sky, a paradise that to us means only a lawn to be cut, storm windows to be put on, and a commutation ticket to be bought the end of every month.

Going so high that she married a school teacher made Sara a success in her world. It is a crude world. too. But the author, wringing the story out of the depths of her heart, somehow transforms herself into a stately Druid priestess, singing sagas.

Bread Givers belongs among those few books that are of contemporary America, a faithful picture without monotony, an exciting account without cheapness. It lacks cant and it lacks prejudice. It is a perfect example of high art in heartthrobs. “It wasn’t my father. but the generations who made my father whose weight was still upon me,” concludes the story.

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

Jewish Women in Novels by Early Jewish Female Writers

More about Bread Givers

- Overview on Encyclopedia.com

- Bread Givers and Becoming a Person (Tenement Museum)

- Jewish Women’s Archive

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

Leave a Reply