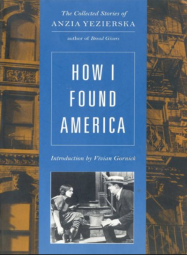

How I Found America: The Collected Stories of Anzia Yezierska

By Nava Atlas | On July 3, 2019 | Updated September 4, 2022 | Comments (0)

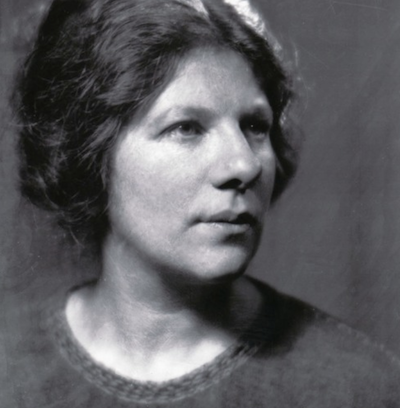

Anzia Yezierska (1880 – 1970) was a writer whose body of work focused on the Jewish immigrant experience in America in the early 1900s.

Born in an area that’s now Poland but which was part of the Russian Empire when she was was a child, her family arrived in New York City’s Lower East Side during the immigration wave of the late 1800s. Anzia, then in her early teens, never shed the feeling of being an outsider looking in.

All of Yezierska’s short stories are collected in How I Found America: Collected Stories of Anzia Yezierska, 1991. In her introduction to the book, literary critic Vivian Gornick wrote:

“She was a misfit all her life. Throughout the years, she saw herself standing on the street with her nose pressed against the bakery window: hungry and shut out. No matter what happened, she felt marginal. Not belonging was her identity, and then her subject. After she began to write, it was her necessity.”

Driven by her ambition, she may have been hampered by her brittle personality and a dose of self-loathing. In her last book, the autobiographical Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950), she wrote: “With a sudden sense of clarity, I realized the battle I thought I was waging against the world had been against myself, against the Jew in me.”

She found a measure of success in the 1920s with her novel, Bread Givers; her short stories even caught the attention of Hollywood, earning her a great deal of money which she eventually lost. Most of her fiction was focused on the Jewish immigrant experience, some of which was semi-autobiographical. Some of her later work addressed Puerto Rican immigrants as well.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anzia Yezierska on Her Struggle to Write Bread Givers

. . . . . . . . . .

A re-evaluation of Yezierska’s work

Having all but disappeared from the literary world long before her death in 1980, there was a wave of revived interest in her work beginning in the mid-1970s, with many re-evaluations of her stories and novels. Bread Givers was reissued in 1975 and 2003, and many of her stories were anthologized, introducing them to new audiences.

Yezierska’s stories are populated with familiar characters — struggling, striving Jewish immigrants, part of the “teeming masses,” who are acutely aware of a gentler, easier life that seems just beyond their reach.

Often, the girl or young woman at the center of the story is someone very much like herself. The female characters’ longing to be seen and heard, and their striving toward a better life is vivid and palpable.

Her alter ego is depicted in stories with painful allusions. In one story, a male character describes the female protagonist as the one with “the starved-dog look in her eyes.”

Her writing isn’t pretty, though it’s quite readable The dialogue feels awkward, but it’s an accurate reflection of the cadence of native Yiddish speakers expressing themselves in English. And though she’s depicting the immigrant experience of a certain people — mainly Eastern European Jews — the immigrant struggle is still, sadly, quite pertinent today.

In her time, Jews and other immigrant groups were often demonized, much as they are today — “welcomed” to the land of the free with lies and stereotypes meant to stir up fear of the Other.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bread Givers by Anzia Yesierska

. . . . . . . . . .

How I Found America by Anzia Yezierska

From the 1991 Persea Books edition of How I Found America: The Collected Stories of Anzia Yezierska:

In evoking the joy and pain of the Jewish immigrant experience, Anzia Yezierska has no peer.

Her stories and novels, written from the 1920s to the 1960s, immortalized the Jews of the Lower East Side. In direct, emotionally powerful prose, she wrote about immigrants like herself as they struggled to emerge from poverty and to partake of America’s promise.

How I found America gathers together twenty-seven stories, virtually all of Yezierska’s short fiction. It includes, in their entirety, the two collections published during her lifetime — Hungry Hearts, the volume which catapulted its young author out of her humble circumstances and into the world of the successful, and Children of Loneliness, a rich and revealing collection, which has been long out of print — as well as seven additional stories, may about old age.

Widely anthologized classics like “The Fat of the Land,” “Children of Loneliness,” and “How I Found America” stand alongside equally remarkable but lesser-known works such as “The Lost Beautifulness,” “Soap and Water,” and “Brothers.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

How I Found America includes all the stories originally published in Hungry Hearts, among others.

Among the most interesting, certainly, are Yezierska’s stories of old age, “A Chair in Heaven,” “Take Up Your Bed and Walk,” and “The Open Cage,” written in the 1960s when Yezierska’s reputation had waned, when she was living in obscurity once again.

Individually, each story is authentic and immediate, as deeply memorable as a personal experience passed on from one generation to the next. Taken together, they constitute a vivid and enduring portrait of a time and a people.

Yet Yezierska’s stories are not period pieces. They ring with the true feelings of every person who has ever wanted to make something better out of his or her life. As a record of the passionate struggle of the human spirit, they are timeless.

In this complete collection of Yezierska’s short stories, an introduction by Vivian Gornick sets them in a literary and historical context and offers new insight into the quality of Yezierska’s achievement.

. . . . . . . . . .

Looping back to Vivian Gornick’ introduction to How I Found America, we find this painfully accurate assessment:

“Inevitably, in Yezierska’s work, whether the narrator speaks in the first person or the third, the story is divided between the time the character announces her “wild, blind hunger” for her own life, and the time she realizes she is trapped in a “repression” from which hope of release is dim. The strength of this simple repetition is such that it achieves metaphoric status.

Yezierska the immigrant. Yezierska the woman, the permanently bereft child are all trapped in that ‘I want to make from myself a person!’ voice. They galvanize one another. With each cry, the words cut deeper, the situation feels more urgent. The character begins to sound as though she were born to speak her piece in this place and at this time, and in no other.”

Leave a Reply