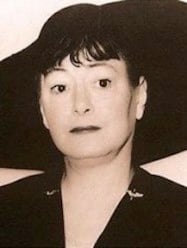

Dorothy Parker, Poet, Wit, and Short Story Writer

By Nava Atlas | On July 19, 2012 | Updated August 25, 2024 | Comments (0)

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967), the American journalist, author, and poet was known for her acid wit. She was one of the founding members of the Algonquin Roundtable, an exclusive group of eminent New York City writers in the early twentieth century.

Parker got her start by writing for magazines, including theatre criticism for Vanity Fair. In the 1920s, she became known for her book review column, “Constant Reader,” in the New Yorker.

Her reviews — some snarky, others sensitive, always pithy — were a pleasure to read. The magazine also published some of her short stories.

“Big Blonde,” one of her most widely read short stories, won the O. Henry Award in 1929. Other well-known works included Enough Rope, Here Lies, and Laments for the Living.

Brendan Gill, the New Yorker critic, wrote in the introduction to a book of her collected works: “Mrs. Parker had been a writer whose robust and acid lucidities had been much feared and admired.”

The bravado and sarcasm of her writings, though, were a veneer for insecurity and loneliness. The high life of early 20th-century Manhattan in which she cast her most of her stories mingled with hints of alcoholism, depression, and difficulties in love relationships that her characters struggled with.

. . . . . . . . . .

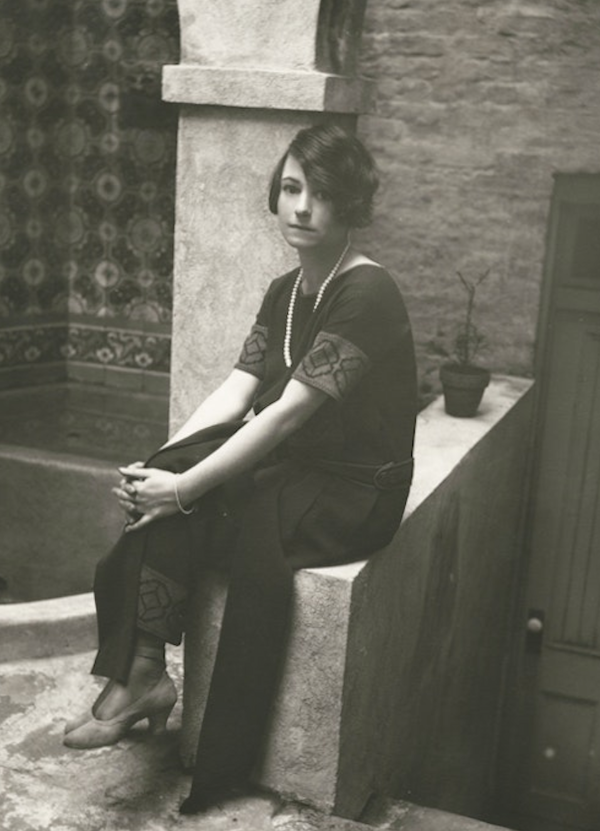

Dorothy Parker around 1920

. . . . . . . . . .

Unhappy childhood, reckless youth

Women and Words by Janet Bukovinsky Teacher (2002) encapsulates Dorothy Parker’s early years and young womanhood:

“Dorothy Rothschild was born in West End, New Jersey, to a Jewish father and a Scottish mother. Her mother died less than a year later. Dorothy would mine the misery of her adolescence, spent with a despised stepmother and uncaring father, in numerous poems and stories.

After graduating from a private school in New Jersey, she found a job at Vogue, writing captions for fashion layouts. Soon she moved to another Conde Nast publication, Vanity Fair, where she was made drama critic.

In her mid-twenties, she married a man named Edward Pond Parker II, from whom she was divorced several years later. She continued to use his name, which she preferred to her own.

For Parker, the Roaring Twenties were loud indeed. She lived a reckless, turbulent life, drinking excessively and often contemplating suicide. ‘What fresh hell is this?’ she wondered in one famous poem.

In another sad, witty rumination about the various distasteful ways to take one’s own life, she concluded that, after all, ‘You might as well live.’ When her poems were first published, critics panned them as frivolous little ditties.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Gems from Dorothy Parker’s Book Reviews

. . . . . . . . . .

The New Yorker and Algonquin Roundtable

The prevailing attitude toward Parker’s work as frivolous changed when one of her stories was published in the New Yorker. After that, her work became a staple in the magazine, with frequent stories and a regular book review column, Constant Reader, which made good use of her wit and snark.

“Upton Sinclair is his own King Charles’ head. He cannot keep himself out of his writings, try though he doesn’t,” was a typical jab. Read more gems from Dorothy Parker’s book reviews.

As a member of the New York literary scene in 1920s Parker helped form a group called the Algonquin Round Table. Named for where they met — The Algonquin Hotel — other members included Robert Benchley, Edna Ferber, Harold Ross, and George Kaufman. This group also referred to themselves as the Vicious Circle — they loved sarcasm, gossip, and rapier wit. They continued meeting into the 1930s.

Parker had some pretty impressive drinking buddies in her time as well, including Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, and Ring Lardner.

Dorothy Parker as a writer of verse

Parker was self-aware enough to know that she wasn’t a great poet. Her verses — in turn witty, funny, reflective, and wise — were often tinged with sadness and disappointment. Helping her to gain renown, they appeared in publications such as Life, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and The New York World.

Eventually, her verses would be gathered in Enough Rope (1926), Sunset Gun (1928), Death and Taxes (1931), and Collected Poems: Not So Deep as a Well (1936). In the introduction to The Portable Dorothy Parker, an omnibus of both short stories and poems, W. Somerset Maugham observed:

“Admirable as are Dorothy Parker’s stories, I think it is in her poems that she displays the quintessence of her talent … she has made little songs out of her great sorrows … And how fresh and various they are! Though beautifully polished, they have an air of spontaneity and none can know better than a writer what patient industry is needed to acquire that quality …

In a few short perfect lines she presents herself to you, to take or leave, with her pain, her ribaldry, and her common sense. Now that I have come to consider these affections and proclivities that I have ascribed to her, it occurs to me that we all … possess them; but she possesses them in a heightened, more concentrated form, so that when you read almost any one of her verses you seem to see her as through the wrong end of a perfectly focused microscope.

It is a great gift to be able to do so much in such a little space. However lyrical her mood … her aerial flight is anchored to this pendant world (the phrase is Milton’s) by the golden chain of common sense.”

Hollywood years and more

Parker spent much of the 1930s and 40s in Hollywood, where she wrote screenplays with her second husband, Alan Campbell.They were nominated for a Best Screenplay Academy Award for A Star is Born (1937). They also wrote the screenplay for the Alfred Hitchcock film Saboteur (1942).

Her marriage to Campbell was stormy. The couple divorced, then married one another again, separated, and ultimately lived together until Campbell’s death in 1963.

One of Parker’s last major creative projects was a play titled The Ladies of the Corridor. Staged in 1964, it was about several lonely, aging widows living in a residential hotel. Reviews were negative, and it closed after forty-five performances.

. . . . . . . . . .

8 Short and Not-So-Sweet Verses on Life and Love

. . . . . . . . . .

Political activism & civil rights

Parker became involved with the Communist Party in the 30s, which would later lead to being blacklisted in the 1950s. More importantly, she was an avid supporter of the Civil Rights movement. As a Jew, Parker identified with the oppressed. A 1927 New Yorker story, “Arrangement in Black and White” satirizes white people who claim not to be racist.

She left her estate to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was surprised by her bequest, since the two had never met. Another stipulation provided that if something should happen to Dr. King, which came tragically to pass not long after, that her estate should go to the NAACP. To this day, the NAACP is in charge of her literary estate.

The Baltimore branch of the NAACP designed a garden in her honor, with a plaque that reads:

“Here lie the ashes of Dorothy Parker (1893 – 1967) humorist, writer, critic. Defender of human and civil rights. For her epitaph she suggested, ‘Excuse my dust’.

This memorial garden is dedicated to her noble spirit which celebrated the oneness of humankind and to the bonds of everlasting friendship between black and Jewish people. Dedicated by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. October 28, 1988.”

Dorothy Parker’s later years and legacy

Parker returned to New York City in 1963. Her last years were marred by poor health, and she disavowed her former colleagues of the Algonquin Round Table.

Her accomplishments in fiction and screenwriting notwithstanding, it’s her witty, trenchant verse that’s most remembered. Here Lies, Death and Taxes, and Enough Rope are the best-known collections of her poems. She died on June 7, 1967 at the age of 73. Though her life was turbulent, Dorothy Parker made an indelible mark on American literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Dorothy Parker

- Gems from Dorothy Parker’s Book Reviews

- Hellman & Parker: The Friendship of Two Difficult Women

- Witty & Wise Dorothy Parker Quotes & Verses

- 8 Short and Not-So-Sweet Verses by Dorothy Parker

Major works (selected)

Short fiction collections

- Laments for the Living (1930)

- After Such Pleasures (1933)

- Here Lies: The Collected Stories of Dorothy Parker (1939)

- Collected Stories (1942)

- The Portable Dorothy Parker (1944)

- Complete Stories (1995)

Verse collections

- Enough Rope (1926) – full text

- Sunset Gun (1928)

- Death and Taxes (1931)

- Collected Poems: Not So Deep as a Well (1936)

- Collected Poetry (1944)

- Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker (1996)

Biographies

- Dorothy Parker: In Her Own Words by Dorothy Parker and Barry Day (2004)

- Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? by Marion Meade (1987)

- A Journey into Dorothy Parker’s New York by Kevin C. Fitzpatrick and Marion Meade (2005)

More information and sources

- Dorothy Parker Society

- Jewish Women’s Archive

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of Parker’s works on Goodreads

- Poets.org

- Poetry Foundation

Leave a Reply