Finding Your Writing Voice: The Essential Quest

By Nava Atlas | On September 15, 2016 | Updated February 16, 2020 | Comments (0)

“Finding your writing voice” is a directive that teeters on cliché. Yet, what’s more important than developing a distinctive personality in print?

It takes a long time for writers, especially women, to raise their writing voices above a proverbial whisper. All those familiar “Who do you think you are …” demons rush in to fill the void where confidence should have been firmly in place.

Without a firm grip on voice, you’re left either with whispering shyly, or its flip side, endlessly blathering streams of overwrought prose or poetry, the literary equivalent of nervous chatter.

What advice would revered classic authors have for those of us still seeking to find or define our voice and style? Here are a few thoughts from writers who went through much the same as most of us, and emerged to tell the tale:

. . . . . . . . . .

Willa Cather

“When I was in college and immediately after graduation, I did newspaper work. I found that newspaper writing did a great deal of good for me in working off the purple flurry of my early writing.

Every young writer has to work off the “fine writing” stage. It was a painful period in which I overcame my florid, exaggerated, foamy-at-the-mouth, adjective-spree period. I knew even then it was a crime to write like I did, but I had to get the adjectives and the youthful fervor worked off.

I believe every young writer must write whole books of extravagant language to get it out. It is agony to be smothered in your own florescence, and to be forced to dump great cartloads of your posies out in the road before you find that one posy that will fit in the right place…” ( Willa Cather, from an interview, 1915)

. . . . . . . . . .

Anaïs Nin

“I didn’t have any particular gift in my twenties. I didn’t have any exceptional qualities … The only reason I finally was able to say exactly what I felt was because, like a pianist practicing, I wrote every day. There was no more than that. There was no studying of writing, there was no literary discipline, there was only the reading and receiving of experience.” (Anais Nïn, from an essay, 1975)

. . . . . . . . . .

Louisa May Alcott

“Each person’s method is no rule for another. Each must work in [her] own way, and the only drill needed is to keep writing and profit from criticism …

Read the best books, and they will improve your style. See and hear good speakers and wise people, and learn of them. Work for twenty years, and then you may some day find that you have a style and place of your own, and you can command good pay for the same things no one would take when you were unknown. “(Louisa May Alcott, from a letter to a reader, 1878)

. . . . . . . . . .

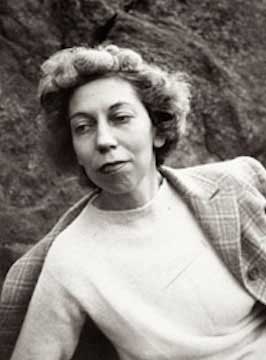

Eudora Welty

“Since we must and do write each in our own way, we may during actual writing get more lasting instruction not from another’s work, whatever its blessings, however better it is than ours, but from our own poor scratched-over pages. For these we can hold up to life. That is, we are born with a mind and heart to hold each page up to and to ask: Is it valid?” (Eudora Welty)

. . . . . . . . . .

Find the courage to use your voice

I suspect that most of us have an inkling of what our literary voice should be, but what’s missing is the courage to use it. Raised to be good girls, many of us are reluctant to sound too strong, assertive, unconventional, or too much like the self we know is in there somewhere, clamoring to come out.

The best remedy, simple though it seems, is to write in quantity, vastly if possible, allowing yourself to do mediocre (or even terrible) work, a practice that will eventually peel back the layers of self-consciousness to reveal a true voice.

As for me, I still like to sit in corners in restaurants and at parties, but on the page—not so much any more.

Leave a Reply