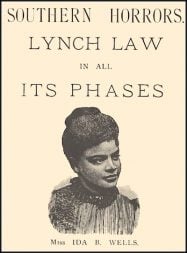

Lynch Law in All its Phases, 1892 Speech by Ida B. Wells (excerpt)

By Dana Rubin | On March 3, 2023 | Updated March 4, 2023 | Comments (0)

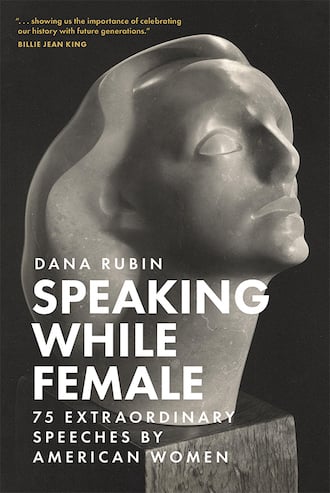

This portion of “Lynch Law in All its Phases,” Ida B. Wells’ 1892 speech given in Boston, is excerpted from Speaking While Female: 75 Extraordinary Speeches by American Women by Dana Rubin. Amplify Publishing Group, 2023.

From the publisher:

“This monumental collection of speeches charts the story of America as it unfolded through the decades, showing that at every critical juncture, women were speaking. It’s a long-needed corrective to the story we have always told ourselves about whose ideas and voices shaped the nation—a search for long-buried truths, a celebration, and an inspiration.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Available now from Amplify Publishing

and for pre-order on Bookshop.org* and Amazon.*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ida B Wells’ 1892 lynch law speech—an introduction

Born into slavery, journalist Ida B. Wells grew up in the South and intended to stay there, believing that with rising wealth and education, thrift, and economy — the doctrine of self-help — Blacks would be accepted into the wider American culture.

But everything changed for her in March 1892, when a fight outside a store in a Memphis neighborhood known as “the Curve” led to the wounding of two White police officers.

Three Black men were arrested, including her close friend, Tom Moss. While in police custody, the men were tortured, and as Wells put it, “found in an old field horribly shot to pieces.”

In an 1893 speech at Boston’s Tremont Temple, Wells did not spare her audience the wrenching details. Moss, she said, had “begged for his life, for the sake of his wife, his little daughter and his unborn infant.” His last word to his tormenters were: “If you will kill us, turn our faces to the West.”

As Wells put it: “I have no power to describe the feeling of horror that possessed every member of the race in Memphis when the truth dawned upon us that the protection of the law which we had so long enjoyed was no longer ours; all had been destroyed in a night.”

Death threats in the wake of those events drove Wells to Chicago, where she made her life’s mission the campaign against lynching – essentially, mob-driven murder of individuals with no due process of law. She investigated dozens of abhorrent cases, conducted countless interviews, collected data, and used her own insubstantial funds to publish her findings.

She also wrote and spoke bluntly about “that old threadbare lie that Negro men rape White women” as a would-be justification for lynching.

An impassioned speaker, she made her case at large conferences, in meeting halls, and in modest churches, helping turn the tide against the atrocity of lynching with her words. It was an uphill battle. She endured harassment and financial hardship. Most of her editorials and articles were published in the Black-owned press, and only occasionally picked up by mainstream publications.

In 1898, she went to the White House to plead with President William McKinley for federal response to a lynching in South Carolina, and for compensation for the victim’s widow and children. She told him that in the previous twenty years, some ten thousand Black citizens had been lynched in America.

Ida B. Wells passed away in 1931. At the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, one of her most enduring lines is emblazoned on the wall:

“The way to right wrongs its to turn the light of truth on them.”

Contributed by Dana Rubin, a consultant, speechwriter, and speaker focused on expanding diverse voices and viewpoints in the public discourse. She works with organizations to develop their talent and support underrepresented voices in becoming recognized experts, brand ambassadors, rainmakers, and role models for the next generation.

An award-winning journalist, she lives in New York, where she writes and speaks about the history of women’s speech and voice. She created the Speaking While Female Speech Bank to broaden our understanding of who actually spoke in history. Visit SpeakingWhileFemale.co to find more speeches by women.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Ida B. Wells

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ida B. Wells: “Lynch Law in All its Phases”

February 13, 1893 — Boston Monday Lectureship, Tremont Temple, Boston MA

I am before the American people today through no inclination of my own, but because of a deep seated conviction that the country at large does not know the extent to which lynch law prevails in parts of the Republic nor the conditions which force into exile those who speak the truth. I cannot believe that the apathy and indifference which so largely obtains regarding mob rule is other than the result of ignorance of the true situation.

And yet, the observing and thoughtful must know that in one section, at least, of our common country, a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, means a government by the mob; where the land of the free and home of the brave means a land of lawlessness, murder and outrage; and where liberty of speech means the license of might to destroy the business and drive from home those who exercise this privilege contrary to the will of the mob.

Repeated attacks on the life, liberty and happiness of any citizen or class of citizens are attacks on distinctive American institutions; such attacks imperiling as they do the foundation of government, law and order, merit the thoughtful consideration of far sighted Americans; not from a standpoint of sentiment, not even so much from a standpoint of justice to a weak race, as from a desire to preserve our institutions.

The race problem or negro question, as it has been called, has been omnipresent and all pervading since long before the Afro-American was raised from the degradation of the slave to the dignity of the citizen. It has never been settled because the right methods have not been employed in the solution.

It is the Banquo’s ghost of politics, religion, and sociology which will not down at the bidding of those who are tormented with its ubiquitous appearance on every occasion.

Times without number, since invested with citizenship, the race has been indicted for ignorance, immorality and general worthlessness declared guilty and executed by its self constituted judges. The operations of law do not dispose of negroes fast enough, and lynching bees have become the favorite pastime of the South.

As excuse for the same, a new cry, as false as it is foul, is raised in an effort to blast race character, a cry which has proclaimed to the world that virtue and innocence are violated by Afro-Americans who must be killed like wild beasts to protect womanhood and childhood.

Born and reared in the South, I had never expected to live elsewhere. Until this past year I was one among those who believed the condition of masses gave large excuse for the humiliations and proscriptions under which we labored; that when wealth, education and character became more general among us, the cause being removed the effect would cease, and justice being accorded to all alike.

I shared the general belief that good newspapers entering regularly the homes of our people in every state could do more to bring about this result than any agency. Preaching the doctrine of self help, thrift and economy every week, they would be the teachers to those who had been deprived of school advantages, yet were making history every day and train to think for themselves our mental children of a larger growth.

And so, three years ago last June, I became editor and part owner of the Memphis Free Speech. As editor, I had occasion to criticize the city School Board’s employment of inefficient teachers and poor school buildings for Afro-American children. I was in the employ of that board at the time, and at the close of that school term one year ago, was not re elected to a position I had held in the city schools for seven years.

Accepting the decision of the Board of Education, I set out to make a race newspaper pay a thing which older and wiser heads said could not be done. But there were enough of our people in Memphis and surrounding territory to support a paper, and I believed they would do so.

With nine months hard work the circulation increased from 1,500 to 3,500; in twelve months it was on a good paying basis. Throughout the Mississippi Valley in Arkansas, Tennessee and Mississippi on plantations and in towns, the demand for and interest in the paper increased among the masses. The newsboys who would not sell it on the trains, voluntarily testified that they had never known colored people to demand a paper so eagerly.

To make the paper a paying business I became advertising agent, solicitor, as well as editor, and was continually on the go. Wherever I went among the people, I gave them in church, school, public gatherings, and home, the benefit of my honest conviction that maintenance of character, money getting and education would finally solve our problem and that it depended us to say how soon this would be brought about.

This sentiment bore good fruit in Memphis. We had nice homes, representatives in almost every branch of business and profession, and refined society. We had learned helping each other helped all, and every well conducted business by Afro-Americans prospered.

With all our proscription in theatres, hotels and railroads, we had never had a lynching and did not believe we could have one. There had been lynchings and brutal outrages of all sorts in our state and those adjoining us, but we had confidence and pride in our city and the majesty of its laws. So far in advance of other Southern cities was ours, we were content to endure the evils we had, to labor and to wait.

But there was a rude awakening. On the morning of March 9, the bodies of three of our best young men were found in an old field horribly shot to pieces. These young men had owned and operated the “People’s Grocery,” situated at what was known as the Curve, a suburb made up almost entirely of colored people about a mile from city limits.

Thomas Moss, one of the oldest letter carriers in the city, was president of the company, Cal McDowell was manager and Will Stewart was a clerk. There were about ten other stockholders, all colored men.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The young men were well known and popular and their business flourished, and that of Barrett, a white grocer who kept store there before the “People’s Grocery” was established, went down. One day an officer came to the “People’s Grocery” and inquired for a colored man who lived in the neighborhood, and for whom the officer had a warrant.

Barrett was with him and when McDowell said he knew nothing as to the whereabouts of the man for whom they were searching, Barrett, not the officer, then accused McDowell of harboring the man, and McDowell gave the lie.

Barrett drew his pistol and struck McDowell with it; thereupon McDowell who was a tall, fine looking six footer, took Barrett’s pistol from him, knocked him down and gave him a good thrashing, while Will Stewart, the clerk, kept the special officer at bay. Barrett went to town, swore out a warrant for their arrest on a charge of assault and battery.

McDowell went before the Criminal Court, immediately gave bond and returned to his store. Barrett then threatened (to use his own words) that he was going to clean out the whole store.

Knowing how anxious he was to destroy their business, these young men consulted a lawyer who told them they were justified in defending themselves if attacked, as they were a mile beyond city limits and police protection. They accordingly armed several of their friends not to assail, but to resist the threatened Saturday night attack.

When they saw Barrett enter the front door and a half dozen men at the rear door at 11 o’clock that night, they supposed the attack was on and immediately fired into the crowd, wounding three men.

These men, dressed in citizen’s clothes, turned out to be deputies who claimed to be hunting for another man for whom they had a warrant, and whom any one of them could have arrested without trouble. When these men found they had fired upon officer of the law, they threw away their firearms and submitted to arrest, confident they should establish their innocence of intent to fire upon officers of the law.

The daily papers in flaming headlines roused the evil passions of whites, denounced these poor boys in unmeasured terms, nor permitted a word in their own defense.

The neighborhood of the Curve was searched next day, and about thirty persons were thrown into jail, charged with conspiracy. No communication was to be had with friends any of the three days these men were in jail; bail was refused and Thomas Moss was not allowed to eat the food his wife prepared for him.

The judge is reported to have said, “Any one can see them after three days.” They were seen after three days, but they were no longer able to respond to the greetings of friends. On Tuesday following the shootings at the grocery, the papers which had made much of the sufferings of the wounded deputies, and promised it would go hard with those who did the shooting, if they died, announced that the officers were all out of danger, and would recover.

Read the rest of this speech at Speaking While Female.

Sources

- Our Day: A Record and Review of Current Reform 11 (January-June), 1893, pp. 333-347

- Our Day, ed. Joseph Cook, May 1893

- Ida B. Wells-Barnett: An Exploratory Study of an American Black Woman, 1893-1930, by Mildred Thompson (New York: Carlson), 1990, p. 177

More about Ida B. Wells

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply