Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist

By Angelica Shirley Carpenter | On October 17, 2018 | Updated November 28, 2020 | Comments (0)

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born in 1826 in Cicero, New York, near Syracuse. She lived all her life in the Syracuse area but also spent time with her adult children who lived in Dakota Territory. Her home in Fayetteville, New York, is now a museum.

In 1893, a deputy sheriff knocked on Matilda Joslyn Gage’s door in Fayetteville, New York. He served her with a supreme writ, court papers summoning her to appear before a judge for breaking the law.

“All of the crimes which I was not guilty of rushed through my mind,” she wrote later, “but I failed to remember that I was a born criminal—a woman.” Her crime: registering to vote. The verdict: guilty as charged.

The following excerpt is from Angelica Shirley Carpenter’s biography Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist, published in September 2018 by the South Dakota Historical Society Press, lightly edited for publication here. Reprinted by permission. Sources may be found in the book.

The National Citizen and Ballot Box

In April 1878 Matilda Joslyn Gage bought an Ohio women’s suffrage newspaper, the Ballot Box. Moving it to Syracuse, she renamed it the National Citizen and Ballot Box. As editor and publisher, Matilda did most of the writing, but Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, as corresponding editors, wrote letters to what soon became the official newspaper of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

The monthly publication, “the cheapest paper in the country, $1 a year,” offered three and a half pages of news and a half page of advertisements. Matilda inherited two thousand subscribers.

The National Citizen published letters and firsthand accounts of women’s experiences. Editorials offered a feminist perspective on marriage customs, rape, labor laws, taxes, the status of women in foreign countries, and the church. Matilda wrote a column, “Women, Past and Present,” and covered conventions extensively, knowing that many of her readers could not afford to attend.

She printed selections from the History of Woman Suffrage [a book she was writing with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with Susan B. Anthony as business manager for the project] as they were completed, asking readers to send in corrections.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Matilda Joslyn Gage in 1881 (photo courtesy of the Gage Foundation)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Suffering often from poor health, Matilda kept working on the History and wrote for other publications, too, including a newspaper in San Francisco. When six young girls were arrested for streetwalking in Fayetteville, she protested to the local newspaper. Two of the girls were just fifteen; the men who had hired them were “village respectables” who were not named in court or charged.

As usual, Matilda’s opinion was more liberal than that of her colleagues. She viewed prostitution as an economic rather than a moral issue, the product of unjust labor laws and the lack of education for women.

“Women of every class, condition, rank and name, will find this paper their friend, it matters not how wretched, degraded, fallen they may be,” she said on the front page of each issue of the National Citizen and Ballot Box.

In her paper she described a mother of ten who was jailed for stealing food for her children, and a man who got a shorter sentence for beating his wife than he would have received for beating a horse (six months for a wife, two years for a horse).

She reported on women living collectively and starting cooperative businesses, and she advocated for boarding houses for working women. Leaders of the women’s movement who fought to open universities and professions to women took less interest than Matilda in the rights of female factory workers, but The National Citizen fought for these women, too.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Born Criminal on Bookshop.org*

Born Criminal on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The paper was not completely serious. One article told of a Russian sect which required husbands to confess sins to wives once a week.

“Would not that require the whole week?” Matilda asked.

Matilda, like other feminists, was often called a man-hater. The Vineland Times, a New Jersey paper, criticized the National Citizen: “It is too aggressive, and too bitter against men.”

“As to ‘aggressiveness,’” Matilda responded, “bless your soul, that is the way to carry on a warfare.”

The paper gave Matilda a new forum in which to promote the Native American society she admired. In May 1878 the United States was trying to force citizenship on Native people, who were fighting it.

“Our Indians are in reality foreign powers,” Matilda wrote, “though living among us. With them our country not only has treaty obligations, but pays them, or professes to, annual sums in consideration of such treaties. . . . Compelling them to become citizens would be like the forcible annexation of Cuba, Mexico, or Canada to our government, and as unjust.”

In July Matilda traveled to Rochester, New York, for the thirtieth anniversary celebration of the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention. The convention call said that the meeting would be “largely devoted to reminiscences.” Rochester, known as “The Flower City,” provided beautiful floral decorations for the meeting in the Unitarian church on Fitzhugh Street.

Some blossoms drooped in record high temperatures as old friends greeted each other happily, with damp hugs. Fans fluttered and cooling liquids were offered as people gathered under “twining wreaths, running through the low, wire lattice, about the platform, and in hanging clusters of vines from the chandeliers.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton spoke of progress made in the women’s movement and goals still to be achieved. Letters and telegrams from across the country and from Europe, were read aloud. Lucretia Mott expressed joy at the number of young women sitting on the platform for the first time.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Matilda Joslyn Gage

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Though in her eighty-sixth year,” the History of Woman Suffrage later described Mott, “her enthusiasm for the cause for which she had so long labored seemed still unabated, and her eye sparkled with humor as of yore while giving some amusing reminiscences of encounters with opponents in the early days.”

Mott yielded the podium to Matilda, watching eagerly as her former protégée proposed a series of resolutions. Three of these, written by Matilda herself, became particularly controversial:

Resolved, That as the duty of every individual is self-development, the lessons self-sacrifice and obedience taught women by the Christian church have been fatal, not only to her own highest interests, but through her have also dwarfed and degraded the race.

Resolved, That the fundamental principle of the Protestant reformation, the right of individual conscience and judgment in the interpretation of scripture, heretofore conceded to and exercised by man alone, should now be claimed by woman, and in her most vital interests she should no longer trust authority, but be guided by her own reason.

Resolved, That it is through the perversion of the religious element in woman, cultivating the emotions at the expense of her reason, playing upon her hopes and fears of the future, holding this life with all its high duties forever in abeyance to that which is to come, that she, and the children she has trained, have been so completely subjugated by priestcraft and superstition.

Then Matilda, along with everyone in the hot, crowded church, listened sadly as Lucretia Mott gave what all knew would be her last speech. Her family had tried to stop her from attending the convention, worried that the trip from Philadelphia, in extreme heat, would prove too much for her. But she had insisted on coming, traveling with a friend, and staying in Rochester with her husband’s nephew, a doctor.

The doctor, fearing that she would be exhausted, called for her to stop before she had finished her closing remarks. Climbing down from the platform, Mott continued speaking as she walked down the aisle, swinging her bonnet by one string, as she often did, and shaking hands on either side. The audience rose simultaneously, out of respect for her.

“Good-by, dear Lucretia!” Frederick Douglass called, speaking for all of them.

After the convention, Matilda’s resolutions created a second kind of heat wave in newspapers and pulpits around the country.

. . . . . . . . . . .

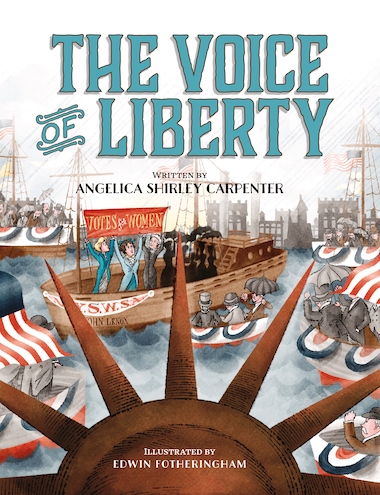

See also: The Voice of Liberty by Angelica Shirley Carpenter

. . . . . . . . . . .

“There was never a clearer illustration,” said The New York World, “of the evil tendencies of the Woman’s Rights movement than in the resolutions adopted at the Rochester convention.”

“Too hazardous,” proclaimed the Rev. A.H. Strong, president of the Baptist Theological Seminary in Rochester. “Bad women would vote.”

“Well, what of it?” Matilda responded, in a National Citizen and Ballot Box editorial, “Have they not equal right with bad men to self-government?”

After three years, paid advertisements to the newspaper decreased. For a time, Matilda subsidized it with her own money, but she could not afford to keep it going. Her last editorial, in October 1881, was called “The End, Not Yet”: “To those who fancy we are near the end of the battle, or that the reformer’s path is strewn with roses, we say them nay.

The thick of the fight has just begun; the hottest part of the warfare is yet to come, and those who enter it must be willing to give up father, mother, and comforts for its sake. Neither shall we who carry on the fight, reap the great reward. We are battling for the good of those who shall come after us; they, not ourselves, shall enter into the harvest.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Angelica Shirley Carpenter has Master’s degrees from the University of Illinois in education and library science. Curator emerita of the Arne Nixon Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at California State University, Fresno, she lives in Fresno.

She has published five previous books about authors: Frances Hodgson Burnett (two books), Robert Louis Stevenson, Lewis Carroll, and L. Frank Baum, who was Matilda’s son-in-law. A past president of the International Wizard of Oz Club, she is active in the Lewis Carroll Society of North America and the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Find out more about her at angelicacarpenter.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply