The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels

By Alex J. Coyne | On November 3, 2023 | Updated June 1, 2025 | Comments (0)

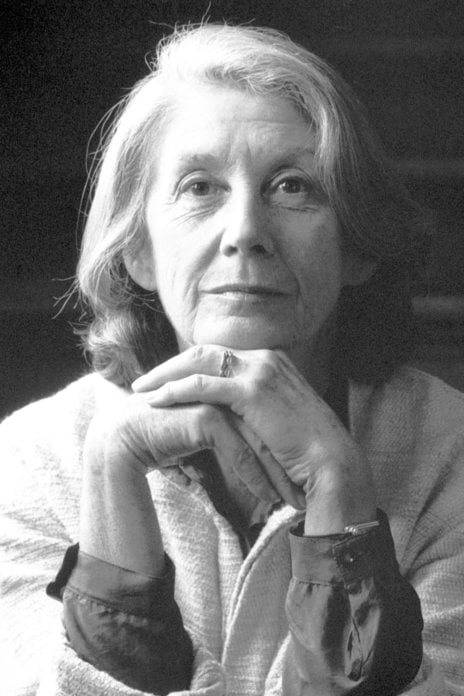

Nadine Gordimer (1923 – 2013) was a South African activist and Nobel Prize-winning author. Presented here is an overview of the banning of Nadine Gordimer’s anti-apartheid novels and other writings, and her legacy as one of the most prominent and outspoken authors of the anti-apartheid movement.

Gordimer was born in Springs, South Africa to Jewish immigrant parents. Her early experiences informed the rest of her life, including witnessing a raid on her family home where a servant’s letters and diaries were confiscated.

Her first novel, The Lying Days, was published in 1953 when apartheid-era censorship by the South African government was at its height.

The Publications Act

According to UCT News, between 1950 and 1990, a total of 26,000 books were banned under the Publications Act of 1974. Governmental bans affected theatre performances, films, television, and books. This reverberated through arts and communication.

Even internationally famous musicals like Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar were banned for reasons of supposed blasphemy. The book Black Beauty was banned merely for including the word “black” on the title page.

After publishing The Lying Days in 1953, Gordimer befriended activists like Bettie du Toit. She cited du Toit’s intentional arrest during a protest action as one of her early inspirations.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nadine Gordimer

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gordimer’s first official ban under the Publications Act law was The Late Bourgeois World, published and banned in 1966. Times Live mentions other books that were banned that year, including Miriam Tlali’s Between Two Worlds (1975) and Es’kia Mphahlele’s Down Second Avenue (1959).

Banned books were completely barred from being read, and couldn’t be sold or shared. If anyone was caught with a banned text, they would be severely punished.

The government ban stretched internationally, and effecting books like The Satanic Bible by Anton LaVey (1969), and other texts that could be seen as anti-religious or against the political views of the time. Even musical artists like Pink Floyd became contraband for being seen as too anti-establishment for local ears.

Renowned poet Ingrid Jonker’s father, Abraham, was one of the prominent National Party figures responsible for banning laws of the time. Abraham headed the censorship commission and had his own staunch opinions on Ingrid’s work. He possibly had his own bias against Gordimer’s writing as well.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

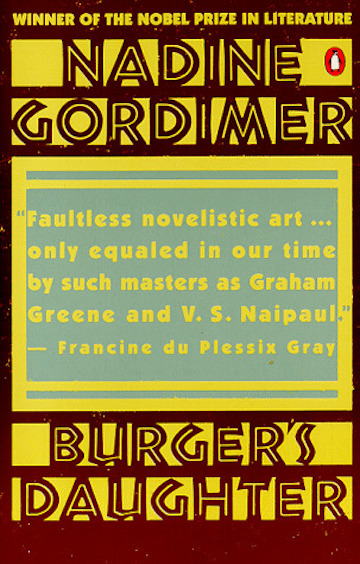

Burger’s Daughter: banned and unbanned

Burger’s Daughter was the second of Gordimer’s works to be banned by the South African apartheid government. The book was partially inspired by her friendship with anti-apartheid lawyers and friends of Nelson Mandela.

In 1979, the book was published and simultaneously banned by the apartheid government’s censorship committee. According to a QZ feature, South Africa’s government of that time would proceed to burn many books in the face of bans, too.

The New York Times reported the book’s ban being canceled in October of the same year: The Government Publications Appeal Board decreed that the book was “inflammatory” rather than harmful and the ban was lifted.

1980: What Happened to Burger’s Daughter

Gordimer couldn’t forget or forgive the government’s stance against her work. In 1980, she published a collection of essays recounting the book’s ban the prior year.

What Happened to Burger’s Daughter (or How South African Censorship Works) is a collection of essays by Gordimer and others.

The text explored the reasons for the apartheid-era ban against her work, and the greater impact this might have had on her writing. In this work, she examines the unfairness of governmental literature bans, and why her work (and others) were banned for no good reasons.

The book’s second chapter, written by the head of the Publications Board, is called “Reasons for the Ban.”

Her next book to be subjected to bans was July’s People, published in 1981 before South Africa eased strict censorship laws. July’s People envisioned a future South Africa where apartheid was ended through a civil war — a concept that the government deemed too dangerous to exist in print.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

South African bans against other arts

In 1984, musicians including Queen protested governmental censorship laws by performing at the Super Bowl in Sun City (located in what was then called Bophuthatswana). Many South Africans traveled to attend, going against laws that didn’t allow them to see the performance (or know the music).

The government’s stance on censorship also affected other arts. Cabaret artist Amanda Strydom famously used the Black Power salute on stage in 1986 during a concert, to the immediate displeasure of the government.

Gordimer continued to write on contentious topics. A Sport of Nature (1987) explored the story of a girl who changes her name to Hillela and subsequently joins the African National Congress (ANC) to marry a member.

Nadine Gordimer’s book bans lifted

Gordimer’s Nobel speech in 1991 mentions A Sport of Nature as a “most hazardous undertaking” under active literature bans.

Laws were revised after 1994, including the Films and Publications Act (65 of 1994), which lifted prior prohibitions on what South Africans were allowed to read and see. Modern censorship laws in Southern Africa are focused on responsible content regulation.

At the time of her death, all of Nadine Gordimer’ books had been unbanned and are available for anyone to read.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author. and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More by Alex Coyne on this site

- Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist

- 8 Essential Novels by South African Author Nadine Gordimer

- Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That

- 6 Notable South African Women Poets

- Olive Schreiner, Author of The Story of a South African Farm

- 10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Writers

- Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid Activist

- The Works of Flora Nwapa

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Nadine Gordimer

- SA History: Nadine Gordimer

- Britannica: Nadine Gordimer

- The Guardian: Obituary for Nadine Gordimer

- Nobel Prize: Nadine Gordimer, 1991

Leave a Reply