Reading and Revisiting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby Stories

By Marcie McCauley | On March 9, 2022 | Updated August 21, 2022 | Comments (0)

Literary Ladies contributor Marcie McCauley delves into children’s book author Beverly Cleary’s beloved character, Ramona Quimby, with this appreciation.

“The sight of that smooth, faintly patterned cloth fills me with longing,” writes Beverly Cleary, recalling an early childhood memory of Thanksgiving.

At first, a moment of calm for the young girl: anticipating relatives seated around the dining room table. Then, activity: she finds a bottle of blue ink, pours some out, presses her hands into it, then “all around the table I go, inking handprints on that smooth white cloth.”

You might guess that the lingering memory would be the moment of discovery. Instead: “All I recall is my satisfaction in marking with ink on that white surface.”

A writer finds her voice

Dedicated Beverly Cleary readers cannot help but see Ramona Quimby in this incident recounted in Beverly’s memoir, A Girl from Yamhill (1988), which covers her early years in rural Oregon, while My Own Two Feet (1995) covers her early working years, filling blank pages with inked stories.

I also think of my fictional friend Ramona when I envision Beverly Bunn (the author’s pre-marriage name) sliding down the banister, trying to find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, pressing her nose against the barbershop window, yearning to look under the swinging doors of a saloon, feeling frustrated when the church ladies mistook her for a picture (a pitcher!) with big ears, and standing on the tilting seat of the fair’s Ferris Wheel.

Others might see a mischievous or rambunctious girl; I see curiosity and intensity, someone stretching to see beyond the edges of a scene.

Early on, young Beverly enjoyed films and comic strips more than books, but soon was lured into reading — via fairy tales— myths, and legends and, eventually, The Dutch Twins by Lucy Fitch Perkins. In the seventh grade, she discovered her love of writing, via an essay about her favorite characters; she couldn’t choose —Tom Sawyer, Peter Pan, and Judy from Daddy Long-Legs were all contenders—so she invented a journey to “Bookland” to accommodate everyone. There’s more about Beverly’s love of story and how it influenced her writing career in this brief biography.

In her second memoir, Cleary describes the Suzzallo Library in Washington: “a cathedral-like building that seemed elaborate after Cal[ifornia]’s neoclassical Doe library.” She attended the School of Librarianship, under the guidance of Miss Siri Andrews, whose “courses took me back to my childhood. The slogan of children’s librarians was ‘The right book for the right child.’”

Cleary’s studies intensified her dedication to storytelling: “Most of my evenings, I read, read, read. There was so much I needed to learn, so many books to become acquainted with.” But she was ultimately inspired to write her first book for the boys she met while working in a library, who asked for books about boys like themselves.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Henry Huggins makes way for Ramona

Henry Huggins (1950) was published ten years after Beverly Bunn married and became Beverly Cleary. In her introduction to its 2016 reprint, she emphasizes the importance of believability and relevance, in her efforts to pull young readers into stories: “Henry would have a dog, an ordinary city mutt because dog stories so often seemed to be about noble country dogs.”

She also describes her surprise over her first book being about Henry: “I assumed I would write about a girl. After all, I had been a girl, hadn’t I?”

You might say that Ramona was both an unexpected and accidental heroine. Cleary had been an only child and, recognizing that all her characters were only children too, she determined to give one of them a sibling:

“When it came time to name the sister, I overheard a neighbor call out to another whose name was Ramona. I wrote in ‘Ramona’, made several references to her, gave her one brief scene, and thought that was the end. Little did I dream, to use a trite expression from books of my childhood, that she would take over books of her own, that she would grow and become a well-known and loved character.”

This is no exaggeration: Ramona’s emergence in Henry Huggins is brief indeed:

“Beezus’s real name was Beatrice, but her little sister Ramona called her Beezus and now everyone else did, too. Beezus and Ramona already had a cat, three white rats, and a turtle, so one fish wouldn’t make much difference. It took Henry a long time to decide which guppy to give her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Ramona blossoms

Years later, Cleary’s editor Elizabeth Hamilton suggested Ramona could have her own book. Readers then encounter Henry through her eyes, in Ramona the Pest (1968): “She had known Henry and his dog Ribsy as long as she could remember, and she admired Henry because not only was he a traffic boy, he also delivered papers.”

Now Ramona is five years old, and she’s starting kindergarten. “People who called her a pest did not understand that a littler person sometimes had to be a little bit noisier and a little bit more stubborn in order to be noticed at all.”

In Ramona the Brave (1975), she is about to start first grade, and she is afraid of the gorilla in the book Wild Animals of Africa in her bookshelf. Her mom has a new bookkeeping job at their doctor’s office, and the world begins to widen in positive and negative ways.

“Agreeing was so pleasant she wished she and her sister could agree more often. Unfortunately, there were many things to disagree about—whose turn it was to feed Picky-picky, the old yellow cat, who should change the paper under Picky-Picky’s dish, whose washcloth had been left sopping in the bathtub because someone had not wrung it out, and whose dirty underwear had been left in whose half of the room.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In Ramona and Her Father (1977), Picky-Picky eats the jack-o-lantern because he hates the cheaper food purchased while the family has only one income.

When the girls go to Mrs. Swink’s house to interview her for Beezus’s school project, they learn what her girlhood had been like: “Nothing very exciting, I’m afraid. I helped with the dishes and read a lot of books from the library. The Red Fairy Book and Blue Fairy Book and all the rest.” Ramona’s life is so much more interesting.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Interesting, but still ordinary: in Ramona and Her Mother (1979) she learns how to write in cursive and gets her first hair cut.

“Nobody had to tell Ramona that life was full of disappointments. She already knew. She was disappointed every evening because she had to go to bed at eight-thirty and never got to see the end of the eight o’clock movie on television. She had seen many beginnings but no endings.”

In Ramona, Age 8 (1981), Ramona and Beezus cook dinner by themselves for the first time, and Ramona starts into DEAR—Drop Everything and Read— at school. Ramona’s world expands a little with every volume.

“She tried not to think of the half-overheard conversations of her parents after the girls had gone to bed, grown-up talk that Ramona understood just enough to know her parents were concerned about their future.”

In Ramona Forever (1984), Ramona’s father has almost finished earning his teaching credentials and Ramona’s friend Howie gets a unicycle, which means she can ride his bicycle.

“Someone’s nose is out of joint. Ramona had heard them say it many times about children who had new babies in the family. This was their way of talking about children behind their backs in front of them.”

Cleary is consistently respectful with her young characters; she doesn’t cut corners with her grown-ups either.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In Ramona’s World (1999), our heroine is excited about the fourth grade; she is not excited by a copy of Moby Dick, which has almost no quotation marks and small print. Ramona’s inner world has always been rich and complex, but now that her understanding of the wider world is increasing, readers see her begin to process the ever-shifting dynamic of coming-of-age. Beneath just one simple word, she is preparing for what’s next:

““Okay,” said Ramona, but she was thinking about Beezus growing up and about what it would be like to grow up herself. She felt the way she felt when she was reading a good book. She wanted to know what would happen next.”

More than a decade passes between the publication of the last two Ramona books, along with other stories and her two memoirs. Bruce Handy, in Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult (2019), writes:

“I loved Cleary before I knew anything about her, but I loved her even more after reading her two memoirs—The Girl from Yamhill and its sequel, My Own Two Feet—and learning that her career was to some extent fueled by her pique at insipid children’s books, the kind that treat kids as if they were mush-headed or shallow, rather than just young. I haven’t read every word Cleary has written, but I’ve read most of them and I’ve never known her to condescend to children or anyone else. Her books are warm but they have backbone. Her pique has served several generations of readers well.”

And why does Ramona stand out in that lauded landscape? In a 2006 HarperCollins interview, “Celebrate Reading with Beverly Cleary,” the author is succinct and clear: “She does not learn to be a better girl.”

Children, she believes, long for the same universal things: home, parents who love them, friends, and teachers they love. Ramona need not learn to be a better girl—she simply must be Ramona. It’s more than enough: most of the letters Cleary received during her career were about either Dear Mr. Henshaw or Ramona.

Cleary doesn’t revisit her characters in her mind to think of new adventures for them. Children enjoy rereading their favorite stories, she says, in that 2016 edition of Henry Huggins, and “by doing that, they learn.”

So does Ramona: “I’ve read all my books a million times,” said Ramona, who usually enjoyed rereading her favorites.” (From Ramona’s World) On occasion, Ramona would come into Cleary’s mind, though, and Cleary would think something like “Oh, Ramona would enjoy that” or “I bet Ramona would love to get herself into that mess.”

As though somewhere, independently, Ramona’s “what would happen next” is unfolding.

. . . . . . . . . .

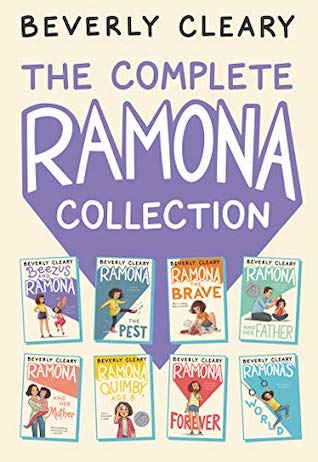

The complete Ramona collection

. . . . . . . . . .

Perusing Anna Katz’s The Art of Ramona Quimby: Sixty-Five Years of Illustrations from Beverly Cleary’s Beloved Books (2020) is akin to rereading the Ramona stories. This kind of bird’s-eye view of the series is fascinating because not only does Ramona’s world broaden as the series unfolds, but readers’ understanding of Ramona and her world also broadens.

In the section devoted to the illustrators of Ramona Forever, for instance, are three different illustrations of a scene: one each from Jacqueline Rogers, Alan Tiegreen, and Tracy Dockray (Louis Darling and Joanne Scribner’s illustrations feature prominently elsewhere):

“Put together, these three illustrations create a zooming-out effect, from Ramona slumped angrily in her chair, to Mrs. Kemp standing over her, to Uncle Hobart trying to make peace between the older woman and the girl. […] This moment could also be understood as a mental zooming out, an expansion of understanding. Ramona suddenly realizes that adults have their own feelings about children, feelings that aren’t always nice.”

The things that happen in Ramona’s mind and Ramona’s world are not always nice. Ramona isn’t always nice either. But reading about her as a girl was like spending time with a friend. We’re still pretty tight. Rereading her as an adult is like a “mental zooming out, an expansion of understanding” as I trace the unexpected complexities of Cleary’s ordinary stories.

Beverly Cleary left her handprints all over me as a young reader and, even now, I’m grateful for the inked trail she left behind.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

Leave a Reply