Marilla of Green Gables: A Future Feminist

By Sarah McCoy | On October 23, 2018 | Updated February 27, 2023 | Comments (0)

Sarah McCoy, author of Marilla of Green Gables (2018) explores the formidable yet loving Marilla Cuthbert (who raises the irrepressible orphan Anne Shirley, better known as Anne of Green Gables) in this meditation on family, community, and character:

It’s clear from the first chapter of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s acclaimed Anne of Green Gables who is in charge: Marilla Cuthbert. My mother first read this novel to me, and I didn’t bat an eyelash at the clear delineation of matriarchal power.

I grew up in a military household. My father was an officer frequently away on TDY (Temporary Duty), deployments, and long hours at his army post. So from the beginning, my mother ruled the roost, and we were not the anomaly.

For most I knew, a no-nonsense queen commander was the standard. It wasn’t until I was much older that I first questioned why the rest of the country hadn’t caught on — no woman president, four-star general or chief justice, not to mention a female priest, pastor, or pope.

Women ruled Avonlea

As far as Montgomery’s fictional Avonlea was concerned, women were boss. Anne of Green Gables opens with Marilla sending her brother Matthew to the train depot to collect an orphan, and it is only by Marilla’s authority that the child, Anne Shirley, is allowed to stay on at Green Gables.

I’ve read Montgomery’s Anne novels forward and backward. While most scholars are quick to identify Anne as the early feminist, with closer examination, it’s unquestionably Marilla that Montgomery empowers, far before our modern feminism was coined. Given Montgomery’s matriarchal family history, this does not surprise.

. . . . . . . . . .

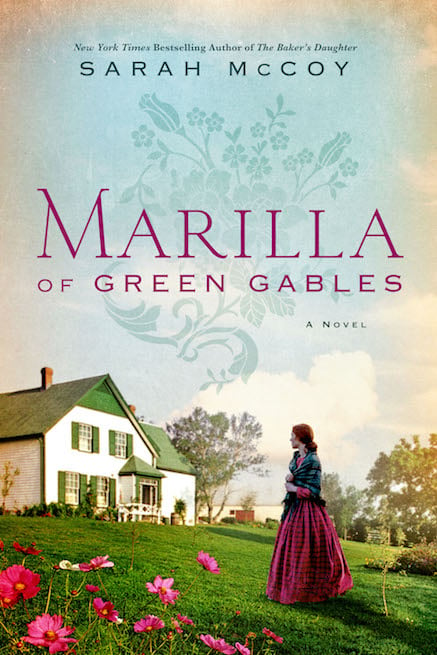

Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

. . . . . . . . . .

It took a village of women

Montgomery’s mother died when she was an infant. Her father moved west to what is now the Saskatchewan Province, remarried, and had a new family. So for all intents and purposes, Montgomery was an orphan who found refuge under the roofs of her maternal grandmother and aunts in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island.

For her, it was the women that created and controlled the worlds she knew. The death of her mother, Clara, was the catalytic start. The void Clara left behind was too large for her father to fill. It took a village of women to raise her, as mirrored in her famous Avonlea.

Growing up, I felt like I knew that village. My mother is one of three girls and a boy. My titis (aunties), tio (uncle) and abuelitos (grandparents) were consistent, commanding forces of good in my life. We were blessed to be stationed in locations that allowed us to be together and when we weren’t, my extended family would often gather for long visits—weeks, holidays, whole summers. Family vacations to our Puerto Rican village of Aibonito were a staple.

I joke that we are related to nearly everyone in town, and that’s no hyperbole. Everyone is a great titi, great tio, or distant cousin. So Montgomery’s Avonlea structure was familiar to me. My Aibonito was the only place I felt wholly grounded and tied to a lineage. I counted on it for stability during a military childhood continually in flux and missing parts (my father).

In particular, I was extremely close with my titis and abuelita. There was an entire woman’s world, distinct from the rest of my loving family and magical—or seemingly so to my girlhood self.

The women daily gathered in the kitchen to cook and tell secrets. My abuelita taught me to crack a coconut, fry chicken, play Spades, and crochet anything I could dream up, all round the old wooden chopping table.

There too, my titis taught me to laugh generously, love fiercely, wear bright red lipstick (because it’s fun), and to sing my own song, even if I didn’t know the words. All of these lessons and more were the structure on which my adult character was built.

I can’t imagine how different I would be if any of those women had been absent—never mind the most principal, my mother, as with Montgomery’s.

But I can say with certainty that like Montgomery’s aunts and grandparents, all of mine would’ve rallied around to raise me. There would’ve been no question as to where or how I fit in the genealogical history. I had a tribe of powerful women to ensure I never lacked role models.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables, a 1908 review

. . . . . . . . . .

Similar again to Montgomery, many Latin American families adhere to a patriarchal structure and mine was no different. Still going strong in his late eighties, my abuelo (grandpa) is one of the most noble, loving people on earth. I adore him.

Speaking from my singular experience, I’ve noticed that most Latino men are adored by the women in their families. That adoration is freely given and freely accepted, thereby making it a unique kind of power. The paralleling qualities to Victorian mores are not lost on me. Perhaps that’s why I always read between the lines of Montgomery’s fictional landscape.

At Green Gables, she was safe to challenge the accepted sentiment that men were to be revered as ‘head of the household’; when in fact, it was women who controlled a majority of the ins and outs of daily living. For propriety’s sake and as a reverend’s wife, it would’ve been nearly impossible for Montgomery to publicly voice early feminist opinion, so she cleverly wove it into her books.

This seemed readily apparent to me, even as a child. After all, I too lived in a world where we honored the traditions of our household: men were venerated— in paid respects if not entirely in authority.

My abuelita did not shirk at my young age when she candidly explained that she had three baby girls in succession (my mother being the third), but would not stop until she had a son for my abuelo.

The price for that treasured boy was my grandmother’s ability to conceive again. So cumbersome was my uncle’s birth that she had to have an emergency hysterectomy following his delivery. The moral of the story? He was worth it. I often wondered if she would’ve said the same had the fourth child been female.

In the alternative universe of Green Gables, a boy orphan was also desired, but Anne Shirley showed up at the door. I read this as Montgomery’s way of indirectly discussing the significance of women—and girls who would one day become women.

Art, education, politics, religion, nature, fashion, food, family, and farm life: all of these are celebrated in her novels as being distinctly under the feminine thumb.

The sister-less Montgomery and Anne Shirley (myself, too) joined forces with Marilla Cuthbert, Rachel Lynde, Diana Barry, Minnie May, Ruby Gillis, and many more female characters in a collective literary sisterhood. It reminded me of the work of modern feminist author, Meg Wolitzer:

“Sisterhood,” Wolitzer wrote in her novel The Female Persuasion, “is about being together with other women in a cause that allows all women to make the individual choices they want.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The author of the Anne of Green Gables series,

L.M. (Lucy Maud) Montgomery

. . . . . . . . . .

This is the very definition of the Montgomery’s Avonlea society—an echo of the present in the past. The village women of Avonlea united to empower each other in making conscious, individual decisions.

From Anne’s famous smashing of the slate over Gilbert Blythe’s head to Marilla’s brewing of red currant wine despite the reverend’s disapproval, and Diana’s excessive imbibing of it; the choices create the stories that make up the chapters of the novel. True to life, though fictional, they are part of the greater feminist narrative.

In her published diaries, Montgomery described how her grandmother, aunts, and female cousins would assemble to prepare meals, sew, have tea, and decide the plans of the day, the month, and even the year. Then they’d return to their respective farms (miles apart) and implemented those collective plans as they deemed best for their nuclear families.

The individual women governed all within the communal house, physically and emblematically, even while the prim culture of the period asserted that their husbands were sovereign. Here, too, Montgomery’s attitude proves far ahead of her time.

She does not recourse to man bashing in her writings. Quite the opposite. As with my own household, the women adored the men. Anne Shirley loved Gilbert Blythe and Gilbert Blythe loved the opinionated Anne Shirley. Marilla Cuthbert cherished her shy, older brother Matthew and he, his stubborn, younger sister. And I assert in my novel Marilla of Green Gables that Marilla deeply loved John Blythe.

In fact, all the characters that Montgomery created are searching earnestly for a heart’s companion—be it male or female, in ardor or bosom friendship. They long for their kindred spirits and will stand to fight if anyone they love is treated unjustly.

Through her stories, we clearly see that Montgomery is a champion of strong villages comprised of people living equality and honorably. I witnessed the quest for this in my own childhood and as a modern woman, I continue to seek it out.

This past June, former First Lady Michelle Obama, author of Becoming, spoke at the American Library Association’s Annual Conference in New Orleans. She emphasized the significance of strong female friendships and fostering networks of nurturing women. She entreated the crowd of readers to “Build your village wherever you are!”

A village like Avonlea. Yes, we must. The appeal is as salient now as it was 110 years ago when the women of Green Gables were first introduced. Art may imitate life, but I also believe that life can imitate art. If we advocate for the principles we admire in our characters, they can act as a catalyst for change in our realities. I, for one, am counting on it. And I believe Lucy Maud Montgomery was too in the character of Marilla Cuthbert.

. . . . . . . . . .

About the author: Sarah McCoy is a New York Times, USA Today, and international bestselling author. McCoy’s work has been featured in Real Simple, The Millions, Your Health Monthly, Huffington Post and other publications.

She has taught English writing at Old Dominion University and at the University of Texas at El Paso. She lives with her husband, an orthopedic sports surgeon, and their dog, Gilbert, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Visit her at SarahMcCoy.com.

Leave a Reply