Jane Austen’s Literary Ambitions (Contrary to the Myth)

By Nava Atlas | On September 1, 2014 | Updated July 6, 2023 | Comments (0)

Picture Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) in her country home, wearing her frilly cap, quill in hand. She writes, as accepted myth would have it, because the fires of genius compel her to, and she doesn’t give two cents about twopence, or any other denomination of financial remuneration. She’s too genteel for that.

Wrong! Austen was keenly interested in the business affairs that pertained to her literary ambitions, and cared deeply about becoming a published author.

Her father and brother, fortunately, were behind her. That was almost a must for a woman of her time who wished to be published. Jane Austen wasn’t “discovered” in any major way; she and her family opted for some of the venues for publishing available to them, none all that attractive or profitable.

Unable to find a good home for Pride and Prejudice, her first fully finished novel, they embarked on a similar mission for Sense and Sensibility, her second.

A reputable publisher found at last

At last, they found a reputable publisher, Thomas Egerton, to print it on a commission basis. Jane was eager to see it in print, regardless of the method, and wrote to her sister, “I am never too busy to think of Sense and Sensibility. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her suckling child.”

Sense and Sensibility was published in 1811 and took two years to sell out the edition of one thousand. When another printing was ordered, she wrote to Cassandra, “I cannot help hoping that many will feel themselves obliged to buy it.”

Settling for less than ideal terms

Pride and Prejudice was soon after also taken by Egerton with little fanfare and even less favorable terms. The Austens decided to sell the copyright outright, as that was another route to getting published. She received £110, and wrote in a letter, “I would rather have had £150, but we could not both be pleased, & I am not at all surprised that he should not chuse [sic] to hazard so much.”

The book was published to critical acclaim in 1813, and was one of the most successful novels of the season. Its author identified on the title page only as “A Lady.” The publisher went through three printings in her lifetime, but having sold the copyright (which lasted twenty-eight years), she received no further remuneration.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Bennett, depicted in an illustrated version of Pride and Prejudice, 1894

From: Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane’s reaction to Pride and Prejudice — her own “darling child”

Jane was exceedingly proud of Pride and Prejudice. Here’s her reaction to its publication, from a letter written to her sister, Cassandra, January 29, 1813:

I hope you received my little parcel by J. Bond on Wednesday evening, my dear Cassandra, and that you will be ready to hear from me again on Sunday, for I feel that I must write to you to-day. I want to tell you that I have got my own darling child [here she refers to Pride and Prejudice] from London.

On Wednesday I received one copy sent down by Falkener, with three lines from Henry to say that he had given another to Charles and sent a third by the coach to Godmersham … The advertisement is in our paper to-day for the first time …

Miss B. dined with us on the very day of the book’s coming, and in the evening we fairly set at it, and read half the first vol. to her, prefacing that, having intelligence from Henry that such a work would soon appear, we had desired him to send it whenever it came out, and I believe it passed with her unsuspected. She was amused, poor soul!

. . . . . . . . . .

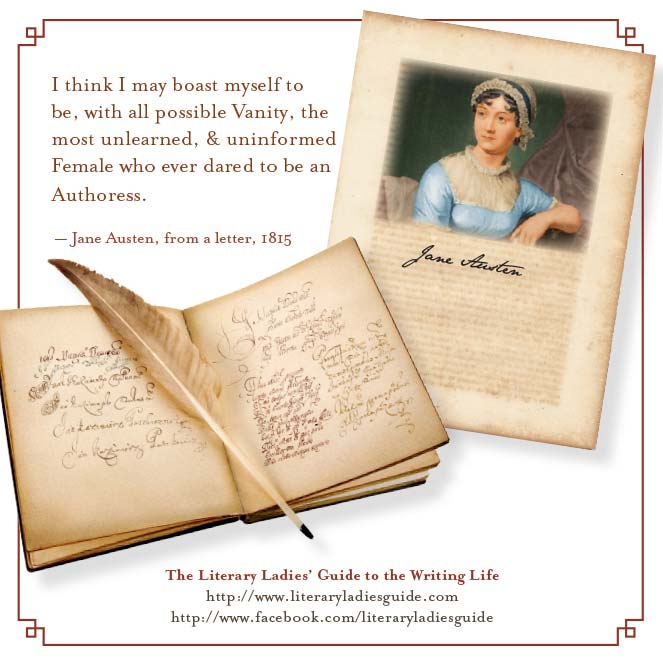

The Biggest Myth About Jane Austen’s Writing Life

. . . . . . . . . .

That she could not help, you know, with two such people to lead the way; but she really does seem to admire Elizabeth. I must confess that I think her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, and how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least, I do not know.

There are a few typical errors; and a “said he,” or a “said she,” would sometimes make the dialogue more immediately clear; but “I do not write for such dull elves” as have not a great deal of ingenuity themselves.

The second volume is shorter than I could wish, but the difference is not so much in reality as in look, there being a larger proportion of narrative in that part. I have lop’t and crop’t so successfully, however, that I imagine it must be rather shorter than “Sense and Sensibility” altogether. Now I will try and write of something else. (— from The Letters of Jane Austen, 1908)

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen Postage Stamps

. . . . . . . . . .

Modest sales, modest success

Despite modest sales by today’s standards, Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility were deemed successes, and set the stage for slow and steady sales of her subsequent books. Austen eagerly awaited payments, and knew just when to expect them, not unlike contemporary authors who hang about the mailbox when royalty time comes along.

In total, she earned about £680 for her books in her lifetime, not a dazzling sum, but the receipt of which gave her great pleasure. It’s difficult to know just how significant this sum was to the Austens.

But to put it in perspective, the dowry of her renowned fictional heroine, Elizabeth Bennett, is worth £1,000. Elizabeth’s future husband, Mr. Darcy, has an income of £10,000 a year, the equivalent of a millionaire’s.

Would she have written without financial reward?

I’m confident that she would have, though she may have been less content with doing so than our romantic notions of them might lead us to believe.

Perhaps the youthful Sylvia Plath summed up the quandary best: “You do it for itself first. If it brings in money, how nice. You do not do it first for money. Money isn’t why you sit down at the typewriter. Not that you don’t want it. It is only too lovely when a profession pays for your bread and butter. With writing, it is maybe, maybe-not.”

Excerpted and adapted from The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life by Nava Atlas.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: The Writing Habits of Jane Austen

Leave a Reply