Jane Austen’s First Attempts at Publishing

By Sarah Fanny Malden | On May 25, 2022 | Updated May 26, 2022 | Comments (0)

Jane Austen’s talent was recognized early on and taken seriously by her entire family. Her father and brothers played key roles in getting her works published, as it wasn’t considered proper for a woman to do so herself in the early 1800s. This 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s first attempts at publishing illustrates the difficulties of the pursuit.

Austen longed to see her work in print, regardless of whether or not it would gain her fame or fortune — but getting it published was important to her, contrary to the myth about her extreme modesty.

Her father and brothers took it upon themselves to seek publication opportunities for Jane’s first works. It was clear that she didn’t write merely for her own amusement but was deeply invested in having her work published and read.

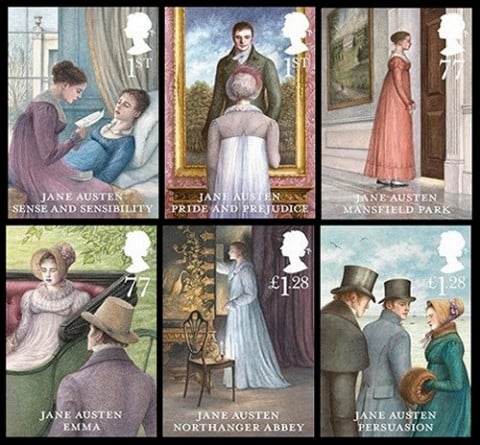

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) is an excellent resource as a 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The publication was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following analysis and plot summary of Sense and Sensibility (1811) focuses on this work, which was Jane Austen‘s first published novel. This excerpt is in the public domain:

……… ………

………

A writing life begins at Steventon

From about the age of twenty to twenty-five — that is, during the five last years of her life at Steventon—Jane had fairly taken up her pen and worked hard with it all the time.

At least three of her best-known novels were written during this period, although, from their not having been published till much later, there is difficulty in fixing the exact dates of their composition.

Pride and Prejudice, however, was begun in October 1796, when she was nearly twenty-one, and finished in August 1797. Three months after it was completed, she began upon what we now know as Sense and Sensibility, but with which, as has been already said, she incorporated a good deal of an earlier story, Elinor and Marianne, originally written in letters. She wrote Northanger Abbey in 1798, soon after finishing Sense and Sensibility.

Even in the quiet life at Steventon, it is difficult to understand how Jane managed to combine so much literary work with all her household and social occupations, for so little was writing a serious business to her that she never mentions it in her letters throughout those years.

It is provoking to read through the pages of correspondence with the sister to whom she told everything and to find them full of little everyday details of home life without a single word upon the subject which would be so interesting now to us.

Writing in the midst of comings and goings

It cannot have been from the shyness that she avoided the topic, for her own family knew of her stories when completed, and, wonderful to relate, she carried on all her writing in the little parsonage sitting room, with everyone coming in and out and pursuing occupations there.

This speaks volumes for the Austen family and their friends; for if even one of them had been a Mrs. Allen, or, worse still, a Miss Bates, all Elizabeth Bennett’s and Emma Woodhouse’s doings might have been forever lost to posterity. While perfectly free from shyness or false shame with her own family about her works, Jane was nevertheless careful to keep their knowledge of them from the outer world.

In spite of her writing being so openly carried on, one intimate friend of family wrote afterward that he “never suspected her of being an authoress.” She always used a little mahogany desk—still in existence—which was easily put away if necessary; and she wrote on very small sheets of paper, which could be quickly concealed without attracting any notice.

When we hear of so much steady work between 1795 and 1800, it seems incredible that she published nothing until 1811; but Jane Austen, like other people, was destined to work her way slowly to success, and her first attempts at getting into print were so disheartening that they deserve to be recorded for the benefit of all despairing young authors.

………..

………..

George Austen’s attempts to help Jane get published

When Pride and Prejudice were finished and given to the family circle, Mr. Austen was much struck by the story and determined to make an effort to get it published. Accordingly, in November 1797, he wrote to Mr. Cadell, the well-known London publisher, as follows:

Sir,

I have in my possession a manuscript novel, comprising 3 vols., about the length of Miss Burney‘s Evelina. As I am well aware of what consequence it is that a work of this sort shd make its first appearance under a respectable name, I apply to you. I shall be much obliged therefore if you will inform me whether you choose to be concerned in it, what will be the expense of publishing it at the author’s risk, and that you will venture to advance for the property of it if on perusal it is approved of. Should you give any encouragement I will send you the work.

I am, Sir, your humble servant,

George Austen.

Steventon, near Overton, Hants,

1st Nov. 1797.

Was Mr. Cadell already overwhelmed with novels in imitation of Evelina, or had he made some unlucky ventures in that line, or was he offended by the epithet “respectable” which Mr. Austen applied to him? It is impossible to tell now; but by the return of the post, and without having seen a line of the book, he declined to undertake it on any terms, and Pride and Prejudice remained unknown to the public till sixteen years later.

Probably Mr. Austen made a mistake in not sending the MS. direct to the publisher at first, for if Mr. Cadell had glanced at the first chapter of it, he must have seen it was no ordinary novel.

……….

……….

Not the first unsuccessful attempt

Nevertheless, this was not the only unsuccessful attempt at a publication that befell Jane Austen. Six years later, in 1803, while living at Bath, she offered Northanger Abbey, which had then undergone careful revision, to a local publisher, who accepted it and gave her—ten pounds!

On second thoughts the worthy man seems to have repented of his bargain, for he never brought it out, and the MS. remained in oblivion for thirteen years longer. By that time Jane Austen had begun to recognize her position as a successful authoress, and thought with justice that if she could recover the MS. it might be published without detracting from her fame.

Henry Austen, her third brother, who often helped her in her communicating with publishers and printers, undertook the errand and found no difficulty whatever in regaining the work, copyright and all, by repaying the original ten pounds.

On this occasion the publisher learned of his error (which Mr. Cadell probably never did); for as soon as Henry Austen had safely concluded the bargain, and gained possession of the MS., he quietly informed the unlucky man that it was by the author of Pride and Prejudice, and left him, we may hope, raging at himself over the opportunity which he had missed of making so good a stroke of business.

Sorrow at the prospect of a move

In 1801 the state of her father’s health brought about the first important change in Jane’s life, for the old home was given up, and she was destined never to spend so much of her life in any other.

The change was a great sorrow to her, but she was allowed very little time to dwell upon it, for Mr. George Austen was a man of prompt decision and rapid action, and having made up his mind, while Jane was away on a visit, that he would leave Steventon, she found, when she returned, that the preparations for departure were being carried on.

Mr. Austen was then upwards of seventy and felt himself no longer fit for the active duties of a clergyman. He did not resign his living but installed his eldest son in them as a kind of perpetual curate, and this arrangement lasted till Mr. Austen’s death in 1805.

At first, the idea of a move was a great grief to Jane, but she was always resolute in seeing the bright side of life, and so she repressed her regrets, and could soon write gaily to her sister:

“I am becoming more and more reconciled to the idea of departure. We have lived long enough in this neighborhood; the Basingstoke balls are certainly on the decline; there is something interesting in the bustle of going away, and the prospect of spending future summers by the sea or in Wales is very delightful.

For a time we shall now possess many of the advantages which I have often thought of with envy in the wives of sailors or soldiers. It must not be generally known, however, that I am not sacrificing a great deal in quitting the country, or I can expect to inspire no tenderness, no interest in those we leave behind.”

A move to Bath

It was fortunate that she had a hopeful disposition to bear her up throughout the worries of house-hunting, and the inevitable discomforts of “a move,” for Cassandra was away at the time, and Mrs. Austen being in delicate health, all the burden fell upon Jane.

Mr. Austen wished to live in Bath, where Mrs. Austen had a married sister, Mrs. Leigh Perrot; so in May 1801 Jane and her parents moved to Bath, where they were to stay with their relatives till they found a house.

Jane’s account of the journey brings before us the gap that railroads have made between her days and ours, for “our journey was perfectly free from accident or event; we changed horses at the end of every stage and paid at almost every turnpike. We had charming weather, hardly any dust, and were exceedingly agreeable as we did not speak above once in three miles.

“We had a very neat chaise from Devizes; it looked almost as well as a gentleman’s, at least as a very shabby gentleman’s. In spite of this advantage, however, we were above three hours coming from thence to the Paragon, and it was half after seven by your clocks before we entered the house. We drank tea as soon as we arrived; and so ends the account of our journey, which my mother bore without any fatigue.”

Composing nothing of importance at Bath

In spite of its dullness, Bath suited both Mr. and Mrs. Austen in many ways, and before long they and their daughters were settled at 4 Sydney Terrace. Sometime later they moved to Green Park Buildings and were there till Mr. Austen’s death in the spring of 1805, when, after a short residence in lodgings in Gay Street, his widow and daughters left Bath “for good.”

Whether the life there had been too full of small bustles for authorship to be easy, or whether the declining health of her parents occupied her too fully for writing, the fact remains that Jane Austen composed nothing of importance while at Bath; perhaps the failure of Northanger Abbey in 1803 disheartened her for a time from further efforts.

One story she did begin, but it was never finished, nor even divided into chapters, so that she cannot have thought seriously of publishing it, and it certainly would not have satisfied her in its present state.

Moving once again, to Southampton

Her next home was in Southampton, where her mother took a house with a garden in Castle Square, and there, Jane was established for four more years of her fast-shortening life.

A friend of hers, Martha Lloyd, to whom she constantly refers in her letters, came to live with them, and this was a source of great happiness to Jane, who frequently mentions her in terms of warm affection. Ultimately Miss Lloyd married Frank Austen, Jane’s youngest brother; but this connection, which would have given her so much pleasure, did not take place till several years after Jane herself had passed away.

The Southampton house was a pleasant one, but the Austens never took root comfortably there, and it is significant of how little Jane felt at home in it, that she wrote absolutely nothing during her four years of Southampton life; not even as much as she had accomplished at Bath.

She had come under circumstances of loss and sorrow which would probably have made any place unattractive to her, and her mother and sister evidently shared her feeling, for as soon as an opportunity occurred of changing their home they gladly seized it.

For some time, Jane had felt herself only a sojourner in strange towns, not really “at home” anywhere; and though she seldom complained of this feeling, it showed itself in the way she had dropped her favorite home pursuit of writing. Now, after the move to Chawton, she dwelt among her own people, and to such a domestic nature as hers, this was a great boon.

A brother comes through

Edward Austen—or Edward Knight as he had now become—deserves the warm gratitude of all Jane Austen’s readers for the arrangement by which his sister found herself again in a real “home,” and felt able to take up once more the writing that she had almost entirely laid aside after leaving Steventon.

As one would like to know whether, on leaving her first home, she ever realized that in that quiet parsonage she had laid the foundations of worldwide fame, so one longs to know whether, on settling at Chawton, she guessed that she should there attain the zenith of her powers and see at least some measure of her future success.

Probably neither idea ever occurred to her; she was too simple-minded to think much of herself and her works at any time, and her principal feeling would have been a peaceful satisfaction at finding herself once more in a house that she could really call “home,” blessed with the continual companionship of her sister, as well as her dearest friend, and enjoying the country life that was associated with her earliest childish recollections.

Leave a Reply