Writing for Madame: The Complex Friendship of Violette Leduc and Simone de Beauvoir

By Elodie Barnes | On April 10, 2022 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (0)

Simone de Beauvoir first met the French author Violette Leduc in 1945. At the time, de Beauvoir and her partner Jean-Paul Sartre were the golden couple of Parisian intellectual circles, while Violette Leduc was a struggling writer mired in poverty.

Their first meeting, in the heady atmosphere of the Café Flore on the Left Bank, came only after Leduc had observed de Beauvoir and Sartre from a distance for several months, gathering the courage to introduce herself.

The resulting friendship seemed unlikely. Yet it lasted for several years, with mutual respect and admiration that survived Leduc’s unrequited attraction to de Beauvoir as well as the differing circumstances of the two women and their wildly diverging experiences of success.

Even today, Simone de Beauvoir remains a feminist icon while Leduc herself is marginalized, little known to either French or English readers, and their rich, complex friendship is often reduced to that of mentor and protegé.

. . . . . . . . .

Simone de Beauvoir and Violette Leduc

. . . . . . . . .

An unlikely friendship

The backgrounds of these two women couldn’t have been more different. Leduc spent her childhood in poverty, as the unwanted daughter of an affair between a servant and the son of a wealthy family. Her education was piecemeal. She was expelled from her boarding school for having an affair with her female music teacher, Denise Hertgès, and she ultimately failed her baccalaureate exam.

Along with Denise (who she lived with until their relationship ended in 1935), she moved to Paris and began working as a secretary for a publishing company. In 1939, she married an old friend, Jacques Mercier, but the marriage only lasted a year and resulted in an abortion that almost killed her. Poor and alone, nursing an unrequited obsession for her friend Maurice Sachs, she attempted to make a living during the war by selling on the black market.

In contrast, de Beauvoir was raised in a bourgeois Parisian family and grew up in the prestigious 6th arrondissement not far from where she would eventually meet Leduc. Despite the family’s fortunes that had suffered during World War I, she attended a prestigious convent boarding school and passed her baccalaureate exams in both math and philosophy in 1925.

She then studied philosophy at the Sorbonne before achieving second place in the agrégation in philosophy, a competitive national postgraduate exam (Jean-Paul Sartre came first). She taught at lycée (high school) level until 1943 when she started making a living from her writing.

Despite their circumstances, the two women found common ground through writing. De Beauvoir later said that her first impression of Leduc was of a “tall, elegant blonde woman with a face both brutally ugly and radiantly alive.” But her attention was truly drawn to the manuscript Leduc handed her, titled “Confessions of a Woman of the World.”

De Beauvoir was skeptical. But instead of the “socialite’s confessions” she had been expecting, it was an extraordinary memoir of childhood that enthralled her so much that she read the first half of it without stopping. Determined that it should be published, she arranged for excerpts to appear in Les Temps Modernes, the journal that she had launched with Sartre, and was instrumental in its eventual acceptance by Gallimard in 1946. It was published as L’Asphyxie (later translated as In the Prison of Her Skin and again as Asphyxia).

It was the start of what would become a complex relationship, in which de Beauvoir became not only Leduc’s lifelong mentor and champion of her work, but also her muse and the subject of her unrequited attraction.

The starving woman

From then on, the two met every other week to discuss Leduc’s work. When de Beauvoir was abroad, she would send letters, but whether in person or in writing, she would always ask Leduc the same question: “Have you been working?” Already realizing that Leduc was prone to fits of paralyzing insecurity and feelings of unworthiness, de Beauvoir was determined to keep her new protege writing.

De Beauvoir’s support also extended to the financial: quickly understanding that Leduc’s poverty was a major obstacle to creativity, she arranged a small monthly stipend, claiming that it was paid by Gallimard.

Leduc became infatuated with de Beauvoir and channeled her obsession into a new novel, L’affamée (later translated as The Starving Woman). The novel’s primary theme is hunger and Leduc’s preoccupation with what the narrator calls “the identical mirages of presence and absence.” It begins with the narrator’s encounter, in a café, with a person she calls Madame and goes on to recount the narrator’s fluctuating state of mind as the relationship with Madame evolves.

Alternately close to and distant from Madame, thrown into despair or ecstasy by one meeting after another, the narrator eventually comes to a tentative acceptance of the reality and limitations of the relationship.

The novel also incorporates De Beauvoir’s insistence that Leduc should write: the narrator, conscious of her own perceived shortcomings, seeks out anything that would make her worthy in the eyes of Madame. “Let her order me to remove my shoes, let her order me to run on rocks, on nails, on pieces of broken glass, on thorns.” But what Madame demands instead is the “purgation” of creativity, and in particular of writing.

De Beauvoir described the novel to her American lover Nelson Algren as “a diary in which she tells everything about her love for me. It is a wonderful book.” However, she rejected Leduc’s advances, writing in 1945:

“Despite my colossal indifference, I was very moved by your letter and your journal. You tell me about my loyalty, I admire yours. I believe thanks to our mutual esteem and trust, we will achieve a balance in our relations. It is strange to find out that you are so precious to someone: you know that you are never precious to yourself; there is a mirage effect which will certainly dissipate quickly. In any case, this feeling cannot bother me more than flatter me … I would like you not to be afraid of me anymore, that you get rid of all this fearful side which seems to me so unjustified. I respect you too much for this kind of mistrust, of apprehension, to have any reason to exist.”

Leduc wrote of her devastation, saying, “She has explained that the feeling I have for her is a mirage. I don’t agree.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

Continued support and a deepening friendship

Far from ending their friendship, however, Leduc’s infatuation only seemed to make it stronger, and De Beauvoir continued to act as a guide and mentor. The two continued to meet every other week, and whenever de Beauvoir was abroad, she sent encouraging and supportive letters to Leduc. From the Sahara, in 1950, she wrote:

“I am wholeheartedly with you in the struggle which you are leading to courageously to write, to live; I admire your energy, I would like this sincere deep esteem to help you a little.”

When Leduc’s novel Ravages had its entire first section censored as obscene for its depiction of a lesbian affair between two schoolgirls, de Beauvoir was “indignant at their prudery, their lack of courage. Sartre too. Do not be broken. You must defend yourself and we will help you…”

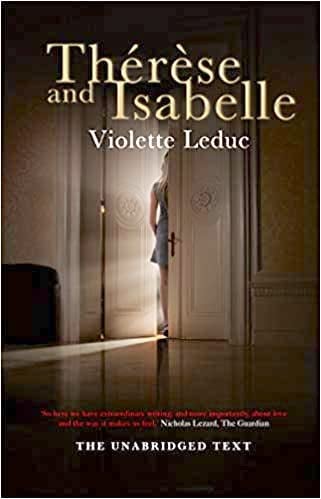

The censored novel was eventually published in 1955, while part of the offending section was later published as a stand-alone novella, Thérèse and Isabelle. It was a commercial success, and a film adaptation was released in 1968. But even this was not published in its entirety in France until 2000, and it didn’t appear in English translation until 2012.

Paranoia, depression, and psychiatric treatment

Despite De Beauvoir’s support, Leduc still struggled to achieve the recognition that she wanted and felt she deserved. Her first two books had been well received by other authors such as Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Jean Genet, who said of Leduc, “She is an extraordinary woman … crazy, ugly, cheap, and poor, but she has a lot of talent.”

The critics, though, were not impressed, and Leduc was mostly ignored by the reading public. Despondent and frustrated, she once said, “I don’t think of myself as not understood. I think of myself as nonexistent.”

By 1956, Leduc was suicidal and paranoid. Depressed by poor book sales and plagued by migraines and insomnia, she became convinced that journalists and critics were ridiculing both her creative failures and what she perceived as her ugliness. In desperation, she asked de Beauvoir to help her arrange an “investigation” into this press harassment.

Alarmed, de Beauvoir persuaded her to go to a psychiatric clinic at Versailles. She remained there for six months, her bills paid by de Beauvoir, undergoing electroconvulsive therapy and a “sleep cure.”

Belated success

Over the next few years, Leduc published two more books, neither of which met with much success. Her health remained fragile, and she began to lose faith in writing. It was de Beauvoir, committed to her belief in Leduc’s talent, who encouraged her to write her life story. The result was La Bâtarde, published in 1964 with a glowing preface by de Beauvoir:

“A woman is descending into the most secret part of herself, and telling us about all she finds there with an unflinching sincerity, as though there were no one listening.”

With this book, Leduc finally achieved some of the success she had craved for so long: it sold 170,000 copies in just a few months and was nominated for both the Prix Goncourt and the Prix Femina.

“The most interesting woman I know”

It wasn’t entirely a one-sided relationship. De Beauvoir considered Leduc “the most interesting woman I know” and was intellectually inspired by the woman who seemed to encapsulate and embody so many of her philosophical theories. She cited Leduc frequently in The Second Sex and drew on Leduc’s life for the book’s analysis of lesbianism.

In Leduc, she saw a vindication of her own philosophy — that we are all free to choose, no matter our past or previous circumstances. To her, Leduc had overcome the limitations of her childhood by choosing to write, thus freeing herself from the constraints of what life had laid down for her. Leduc, incidentally, challenged this theory, saying that “To write is to liberate oneself. Untrue. To write is to change nothing.”

The friendship between the two women lasted until Leduc’s death in 1972 from breast cancer, but it always defied any kind of neat classification. Despite their closeness, de Beauvoir stated in the 1980s that, “I established a certain distance from the very beginning,” while Leduc admitted in her memoirs:

“I shall never understand the meaning of the word love when it applies to her and to me. I do not love her as a mother, I do not love her as a sister, I do not love her as a friend, I do not love her as an enemy, I do not love her as someone absent, I do not love her as someone always close to me. I have never had, nor will I ever have, one second of intimacy with her. If I could no longer see her every other week, darkness would submerge me. She is my reason for living, without having ever made room for me in her life.”

. . . . . . . . .

Violette (2013 film)

. . . . . . . . .

Legacy of the Leduc – de Beauvoir friendship

The complexity and ambiguity surrounding their relationship have proven to be a source of continued fascination: the 2013 film Violette, starring Emmanuelle Devos and directed by Martin Provost, concentrated largely on Leduc and de Beauvoir, and was well received.

And in 2020, when de Beauvoir’s letters to Leduc were sold, auction house Sotheby’s described them as “remarkable … charting a complex and ambiguous relationship…where unrequited amorous passion, tenderness, and mutual admiration tinged with mistrust mingle.”

Perhaps, though, it is best summed up by one of Leduc’s last interviews, given in 1970, in which she poignantly acknowledged, “at the end of my life I will think of my mother, I will think of Simone de Beauvoir, and I will think of my long struggle.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Major works by Violette Leduc

- Asphyxia (translated by Derek Coltman), Gallic Books 2020

- Thérèse and Isabelle (translated by Sophie Lewis), Feminist Press 2015

- La Bâtarde (translated by Derek Coltman), Dalkey Archive Press 2009

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

Leave a Reply