Allison MacKenzie: Coming of Age in Peyton Place

By Francis Booth | On April 23, 2021 | Updated December 20, 2023 | Comments (2)

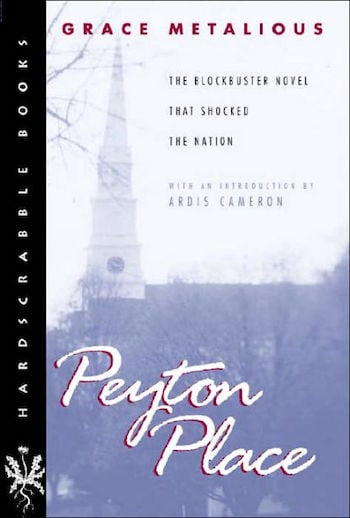

This look at the coming of age of Allison MacKenzie, a central character in Peyton Place, the controversial 1956 novel by Grace Metalious, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

At right, Diane Varsi as Allison MacKenzie in the 1957 film adaptation of Peyton Place.

Peyton Place is set in a small New England town where everyone knows everyone’s business. The story actually takes place in the late 1930s, contrary to popular belief that it’s set in the 1950s. The book’s themes were more than the censors and many critics were prepared to accept.

But the censors were far too late. Peyton Place was already a bestseller by September 1956, and would remain so well into 1957. The novel was banned in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1957 and in Rhode Island in 1959, among many other notable bans and challenges that did nothing to slow the book’s sales.

It sold over 100,000 copies in its first month, compared to the average first novel which sold 3,000 copies, if lucky, in its lifetime. Peyton Place eventually sold over 12 million copies.

Even so, it may be better remembered for the somewhat sanitized 1957 film and the long-running prime time television soap opera, which almost entirely obliterated the original storyline.

The TV series titled Peyton Place began in 1964, running for five seasons until 1969. Even more than the film, it was a mere shadow of the novel. It starred Mia Farrow, age nineteen when the series began, as Allison Mackenzie. As the first nighttime soap opera, it was hugely successful, though it all but obliterated cultural memory of the 1956 novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Grace Metalious

. . . . . . . . . .

A page-to-screen success

Grace Metalious (1924 – 1964), born Marie Grace DeRepentigny, was born into poverty in New England. She married George Metalious and, unlike most other successful female authors who kept their names, published under her husband’s.

Despite their poverty, George attended university and became principal of a school while Grace continued to write, something she had done since she was a student, and in which George encouraged her.

George later said that the novel’s eponymous town and its name were “a composite of all small towns where ugliness rears its head, and where the people try to hide all the skeletons in their closets.”

Grace was thirty when she finished the manuscript; she found a literary agent but had trouble finding a publisher because of the amount of sex it contained. Reviews in serious newspapers condemned the book but that did not stop people buying it. Much later Metalious said, “If I’m a lousy writer, then an awful lot of people have lousy taste.”

She was right. Less than a month after the novel was published, producer and screenwriter Jerry Wald paid her $250,000 for the film rights.

He also paid her as a story consultant though she was not in the end responsible for any of the screenplay and in fact she hated Hollywood, hated how her novel was sanitized, and was appalled by the suggestion that Pat Boone – who wrote a bland advice column for teenagers in Ladies Home Journal – be cast in a leading role.

Still, the $400,000 she made from the film was probably some consolation. The film came out in 1957, featuring nineteen-year-old newcomer Diane Varsi who was far too mature for the role, but was nominated for an Academy Award anyway.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Allison Mackenzie & Selena Cross

Allison hadn’t one friend in the entire school except for Selena Cross. They made a peculiar pair, those two, Selena with her dark, gypsyish beauty, her thirteen-year-old eyes as old as time, and Allison Mackenzie, still plump with residual babyhood, her eyes wide open, guileless and questioning, above that painfully sensitive mouth.

There is also a huge social difference between the two girls: Allison’s mother Constance is discreet and aloof and runs a high-class dress shop – “the women of the town bought almost exclusively from her” – while Selena lives in a rundown shack with her hopeless mother and vile, violent, drunken, and lecherous stepfather who rapes and impregnates her.

In the original manuscript, he was her birth father; the one change that Metalious reluctantly agreed with her publisher before publication was that he should become her stepfather – it hardly lessens the shock when we learn of the rape. In fact, Metalious ripped this episode from a sensational true crime story that happened in staid New England several years before she wrote the novel — and in the real-life version, a young woman murdered her father, who had repeatedly raped her.

“Selena was beautiful while Allison believed herself an unattractive girl, plump in the wrong places, flat in the wrong spots, too long in the legs and too round in the face.” Selena, on the other hand, is “well-developed for her age, with the curves of hips and breasts already discernible under the too short and often threadbare clothes that she wore.”

She has “long dark hair that curled of its own accord in a softly beautiful fashion. Her eyes, too, were dark and slightly slanted, and she had a naturally red, full lipped mouth over well shaped startlingly white teeth.”

Selena is nowhere near as well-read as Allison but she’s much wiser; “wiser with the wisdom learned of poverty and wretchedness. At thirteen, she saw hopelessness as an old enemy, as persistent and inevitable as death.”

Selena cannot understand “what in the world ailed Allison that she could be unhappy in surroundings like these, with a wonderful blonde mother, and a pink and white bedroom of her own.”

Unlike Allison, Selena covets the dresses in Constance’s shop. Constance “could understand a girl looking that way at the sight of a beautiful dress. The only time that Allison ever wore this expression was when she was reading.”

When Constance asks Selena to work part-time in her shop, Selena thinks she is in heaven. Wearing one of the dresses, Constance thinks Selena has “the look of a beautifully sensual, expensively kept woman.”

Selena adores Constance; she thinks: “Someday, I’ll get out, and when I do, I’ll always wear beautiful clothes and talk in a soft voice, just like Mrs. McKenzie.”

Allison may not be popular with the girls – or indeed the boys, not that she cares about boys – but her teacher Miss Thornton likes her. She has a mission:

“If I can teach something to one child, if I can awaken in only one child a sense of beauty, joy in truth, and admission of ignorance and a thirst for knowledge then I am fulfilled. One child, thought Miss Thornton, adjusting her old brown felt, and her mind fastened with love on Allison Mackenzie.”

Allison knows about Miss Thornton’s feelings for her – an unusual example of a teacher having a crush on a girl – but she believes it is “only because Miss Thornton was so ugly and plain herself.”

An absent father

Allison’s mother has never told her the truth about her father. While living in New York City as a young woman, Constance had an affair with the Scottish businessman, but they never married. He already had a wife at the time of the affair and had no intention of marrying Constance. He provided for her and their daughter, who was born out of wedlock.

When Constance returned to Peyton Place with baby Allison, she invented a fictitious short-lived marriage and widowhood. The only kernal of truth was that her lover had died. To make the story work, she has had to subtract a year from Allison’s real age – Allison is a year older than she and everybody else believes.

Allison loves her absent father – or at least the false image she has built up of him – as well as her mother, though they have “little in common with each other; the mother was far too cold and practical a mind to understand the sensitive, dreaming child, and Allison too young and full of hopes and fancies to sympathize with her mother.”

Bookish Allison

Allison is bookish but does not get her love of reading from her mother: Constance “could not understand a twelve-year-old girl keeping her nose in a book. Other girls her age would have been continually in the shop, examining and exclaiming over the boxes of pretty dresses and underwear which arrived there almost daily.”

Unlike Selena, all Allison knows about life she has got from her reading. She has discovered a box of old books in the attic, and is fascinated by them; “she went from de Maupassant to James Hilton without a quiver.

She read Goodbye, Mr Chips and wept in the darkness of her room for an hour while the last line of the story lingered in her mind. ‘I said goodbye to Chips the night before he died.’ Allison began to wonder about God and death.”

But what Allison loves most of all, better than books even, is being alone in the countryside just outside the town where she can “be free from the hatefulness that was school … For a little while she could find pleasure here and forget that her pleasures would be considered babyish and silly by older, more mature twelve-year-old girls.”

“Now that she was quiet and unafraid, she could pretend that she was a child again, and not a twelve-year-old who would be entering high school within less than another year, and who should be interested now in clothes and boys and pale rose lipstick… But away from this place she was awkward, loveless, pitifully aware that she lacked the attraction and poise which she believed that every other girl her age possessed …”

Resisting the path to womanhood

Allison does not want to turn from a girl into a woman, does not want come of age, mentally or physically; the outward attributes of womanhood repel her.

She hates the idea of “hair growing anywhere on her body. Selena already had hair under her arms which she shaved off once a month.” Selena tells Allison that she gets it all over with at once, “my period and my shave.”

Allison agrees this is a good idea but “as far as she was concerned, ‘periods’ were something that happened to other girls. She decided that she would never tolerate such things in herself.’

Allison sends off for a sex education book which she reads carefully to find out about periods; she clearly cannot contemplate asking her mother.

. . . . . . . . . .

Peyton Place by Grace Metalious on Amazon*

Peyton Place — two 1956 reviews

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

A book that’s better than its reputation

Despite its mauling by “serious” critics and its mangling by film and TV producers, the original novel’s reputation for lowbrow sleaze is completely unjustified: in its sensitive and perceptive treatment of both Allison and Selena it is as good a coming-of-age novel as many more vaunted classics.

It is certainly better than Grace Metalious’s later novels, including its hastily written sequel, Return to Peyton Place, 1959, which follows Allison as she grows up to become a writer, writing scurrilous, thinly disguised portraits of the people in Peyton Place and, like her mother, has an affair with a married man.

Success did not bring happiness to Metalious and she died of liver failure following years of heavy drinking at the age of thirty-nine in 1964.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Details here about Constance are wrong.She left PP for the city with high hopes but only reached as far as becoming the mistress of a well off man much older than herself. Her married lover and sugar daddy died when Alison was a baby. He left Constance money in his will. This enabled her to buy the shop when she returned to PP.

Helen, you’re right. I’ll clear up this detail in a bit …