A 1931 review of The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

By Emma Ward | On May 26, 2017 | Updated October 17, 2022 | Comments (0)

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck was the second novel by this iconic American author. Published in 1931, it led the bestseller list for almost two years. The story of a Chinese peasant farmer named Wang Lung and his family, the book was translated more than thirty languages worldwide.

Buck received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938 for her body of work, and the impact of The Good Earth surely contributed to this high honor.

Pearl Buck’s perspective provided an anthropological twist as a Western participant in Chinese culture. She was able to highlight cultural traditions that may be taken for granted by a native author:

“Happy for me that I had such parents, for instead of the narrow and conventional life of the white man in Asia, I lived with the Chinese people and spoke their tongue as I spoke my own. We learned by example to judge people by character and intelligence rather than by race or sect.”

Other themes in the book influenced by early twentieth century Chinese culture include foot binding, opium addiction, oppression of women, material wealth, and human relationships to the earth.

Buck received praise for this work through Life magazine’s list of outstanding books (1924-1944). It was adapted into both a play and movie. Many decades after its publication, it was recommended by Oprah’s Book Club.

The start of Wang Lung’s journey

The story begins with Wang Lung, an impoverished young man who marries a slave girl named O-lan. Throughout their life, they have multiple children and work off their debt in the fields.

Lung is proud of his land but has to find other ways of making money and refuses to sell it. The family moves south, begging on the street during the day and loading cargo at night to survive.

The war between the communists and nationalists had gained momentum, documented through the story as Wang Lung becomes involved in the revolution to liberate the poor from class oppression.

He ends up looting houses of the rich to obtain finances that would move his family back up North. Falling tired of this lifestyle, Lung has an affair and spends his savings on a mistress named Lotus.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck: An Appreciation

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1931 Review of The Good Earth

This review from The Ottawa Citizen, March 28, 1931, the year the book was published, gives a good overview of the plot and themes:

Love of the land, man’s dependence on it and sense of unity with it, has become a staple theme, and one of the most popular with novelists, paradoxically, at the very moment when industrialism rules, and agriculture by machinery is changing farming from a mode of life to a business.

Now comes the echo from the East in Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth, in which the changing times are reflected from a rural district in China — that old mother of both agriculture and industry. The novel’s manifold pictures give the most intimate revelations of rural Chinese life.

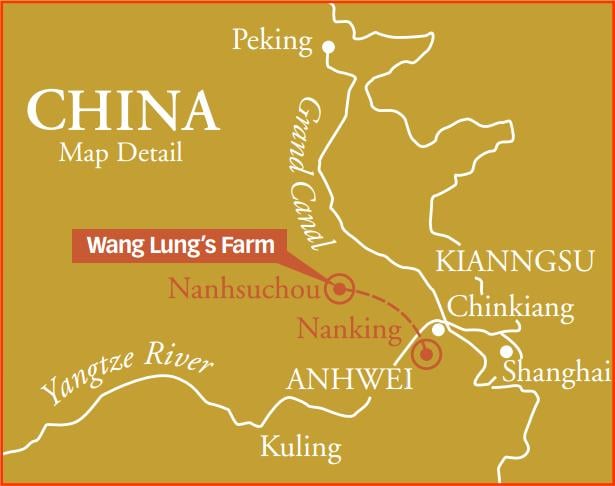

The author lived much of her early life in China, except for a few years at American colleges, and while working on this novel was teaching at Nanking University She is alone, as far as this reviewer’s knowledge extends, in having written a serious Chinese novel without a single white character intervening at any point.

Her scenes have the allure of being strange ad familiar at the same moment; because, beneath habits so different from ours, the yield of crops from the tilling of soil is similar world over, and the struggle of humankind for security amid continual uncertainty an change is universal.

The marriage of Wang Lung and O-Lan, from sustenance to poverty

Opening with the marriage of Wang Lung, the poor young farmer, to a slave maiden, O-Lan, whom he has never seen, the story strikes a note of calm and satisfaction.

For this strong, silent bride brings joy to the simple heart of her lowly lord by setting his house in order and working beside him in the field. She is kind and frugal, and soon there is a surplus with which more land is bought.

Then the drought comes and the starving family makes its way south to the great city. The wife and children beg while Wang Lung drags a rickshaw until he despairs of ever saving enough to take them back to the land. As a desperate measure, and as a means of avoiding poverty for the whole family, he considers selling his daughter into slavery.

A return to the land

But then, unexpected good fortune comes their way and Wang Lung is able to resume farming on an extended scale; thrift and hard work bear fruit. Soon he is a rich landed proprietor, the founder of a “great family,” with a town house and sons who hold responsible positions in business and official life.

In addition to a good, rounded-out story, which concludes with Wang Lung’s death in his seventies, the book is replete with details of Chinese life. One is struck by the extremed poverty of the farmers and city laborers.

At the time of the famines, which come from five to ten years apart, people eat grass and sell their children. While the rich are well educated, illiteracy is the rule among the poor, and ignorance is profound.

The revolution passes him by

The revolution passed Wang Lung’s door in his old age, and the country settled down again without his knowing what the word revolution meant, nor having heard of any political change.

In that unlucky year in the city, he was once handed a piece of revolutionary literature; but as he couldn’t read, he gave the paper to O-lan, who sewed it as stiffening into the sole of a shoe.

Insufficient police protection comes out well in Wang Lung’s discovery that his uncle, who is sponging off him, is second in command in a robber band.

Supporting the uncle means immunity from theft, but the uncle takes advantage of his power to begin blackmail, which Wang Lung counters by teaching his uncle to use opium. Opium is costly but cheaper than blackmail.

A glimpse into Chinese life of the time

Domestic life in all its phases is revealed with candor. While conventions differ from ours — such as a man’s taking a concubine into his home instead of maintaining her outside the home.

The emotions of all the characters are quite comprehensible. We understand why the first and second wives will not speak to each other, and the distress and helplessness of the father as his sons become men and adopt manners that are not to his liking.

As a saga of the land, or as an enlightening study of Chinese life, or as a story of the rise of a family from poverty to affluence and its consequent transfer from rural to urban conditions and back again, The Good Earth is highly recommended.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Good Earth Sequels: Sons and A House Divided

The Good Earth grew into a trilogy that became House of Earth. The narrative spans fifty years. As described by Pearl S. Buck herself:

“When this trilogy began to shape itself, it began, not as a single book, but as the entire span of a Chinese family rising, as nearly all great families do, out of the earth.

The story told in the first book was not the story of a farmer, but a man far more than the average farmer, a man whose hoe was upon the land and would always be, but who used the land as a foundation upon which to build a family.

Nothing in Chinese life, and indeed in human life, is more significant than this rise and fall of families. The founder is often a strong, naïve, clever, simple man, whose children swiftly grow beyond his environment and carry his vigor far and wide into other lines.

In Sons, the original vigor of Wang Lung was carried into war and into trade and money getting and money spending, but already that vigor, first bound into one figure, is dissipated.

As time goes on, it spreads into many sons and many places. In A House Divided the vigor seems quite scattered. Accustomed riches, remoteness from the land, the complicated forces of modern existence, have tempered and even destroyed the strong ruthless unconscious selfishness of the founder. Such has been the history of the great Chinese families.”

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Dragon Seed by Pearl S. Buck

. . . . . . . . .

More about The Good Earth

- Wikipedia

- The Good Earth on IMDb

- Pearl S. Buck International

- Reader Discussion on Goodreads

- Asia Society review

Leave a Reply