Sylvia Townsend Warner

By Elodie Barnes | On June 22, 2020 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (0)

Sylvia Townsend Warner (December 6, 1893 – May 1, 1978) was an English novelist, poet, and musicologist. Best known for her novels Lolly Willowes and The Corner That Held Them, she was also a prolific writer of short stories and contributed to The New Yorker for over forty years.

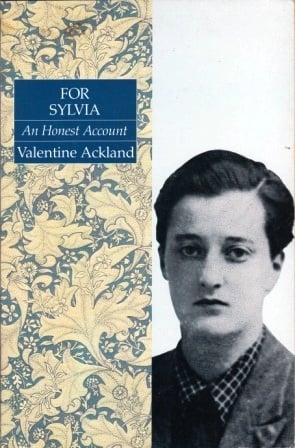

Despite a revival of her work in the 1970s, led by feminist publisher Virago Press, she is still an under-appreciated figure in literature and is probably just as well known for her long-term relationship with Valentine Ackland.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early years

Sylvia was the only child of Harrow schoolmaster George Townsend Warner and his wife, Nora Mary Hudleston. She was a strong-willed and curious child, who loved learning but was withdrawn from kindergarten after a single term.

According to her school report, she distracted the other children with too many questions and mimicked the teachers to the point of insolence. The only positive comment was that she was a musical child who always sang in tune.

After this, Sylvia was taught at home by Nora. The Bible, history, geography, Shakespeare, languages, and music were all taught with flair, alongside vivid stories from Nora’s own childhood in India.

Her father instilled in Sylvia the same passion for history that he himself had. A talented teacher, he was beloved by his pupils and by Sylvia, who adored him though his teaching and housemaster responsibilities often kept him too busy for family.

Sylvia’s relationship with her mother was more difficult and complex. Nora’s affection for her daughter tailed off as Sylvia grew into a tall, lanky, shortsighted girl who showed no interest in any of the social necessities and niceties that Nora herself held so dear.

When, in 1911, Sylvia was of an age to “come out” in society, she drove Nora to distraction by showing very little interest in the proceedings. Later, Sylvia would write that “nothing compensated for my sex,” and felt that Nora resented her for not being a boy.

Generally, though, Sylvia’s upbringing was a comfortable one. Term times at Harrow were interspersed with family holidays, to Switzerland during the winter and to Scotland in the summer. Early in 1914, George bought a piece of land in South Devon intending to build a house for holidays and eventual retirement.

The house, known as Little Zeal, became a permanent home for George and Nora but never for Sylvia. Her relationship with her mother was strained enough: by 1914 she was more than ready to start making her own way.

Outbreak of war and dedication to music

Music had always been important to Sylvia. She was a talented pianist and composer, and when she was 16 began to study formally with the music master at Harrow, Percy Buck. He supported and encouraged her, teaching her the piano and the organ, the history and theory of music, and composition.

He was also her first real lover; they began an affair when Sylvia was 19, and it lasted for seventeen years.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, Sylvia had been due to travel to Europe to study composition with Arnold Schoenberg. Instead, she stayed in England, continuing to study under Buck’s tutelage and the supervision of the Royal College of Music.

She also worked the night shift at a munitions factory in South London. Her father encouraged her to write about her experiences there, and the result was an 8,000-word essay, ‘Behind the Firing Line’, which was published under the name of “A Lady Worker” in Blackwood’s in February 1916. It was Sylvia’s first published piece.

In September of that year, George died, likely from a burst ulcer. His death affected Sylvia badly: she would later write, “My father died when I was twenty-two, and I was mutilated.”

Moving back to Little Zeal to take care of her mother was an ordeal. Their relationship had not improved, and grief made it worse for both of them.

In 1917 she was offered, possibly through Buck’s intervention, a position as editor for a new musicology project: the collecting, editing, and publication of a wealth of Elizabethan church music, which until then had existed only in handwritten form in cathedral books.

The Tudor Church Music project, financed by the Carnegie (UK) Trust, gave her a salary of £3 per week, which was not much to live on but gave her enough to move back to London and away from Nora. Sylvia enjoyed the work and threw herself into it, gaining a reputation as a talented editor who knew her subject.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Life in London and the first novel

Sylvia settled quickly into a relatively quiet life in London. Although she knew many of the people who would become part of the Bloomsbury set, she preferred fewer friendships to large gatherings, and her affair with Percy Buck continued.

Her relationship with her mother also began to improve after Ronald Eiloart, a former pupil of her father’s and a close friend of the family, returned from the war and asked for Nora’s hand in marriage. Sylvia was delighted and the Eiloarts appalled, but the match seemed to suit Nora and so relieved Sylvia of some worry and stress.

Writing was also becoming a large part of Sylvia’s life, taking the place of composing. She was beginning to write poetry, using left-over pieces of the smooth, heavy manuscript paper that she brought home with her from the Carnegie project.

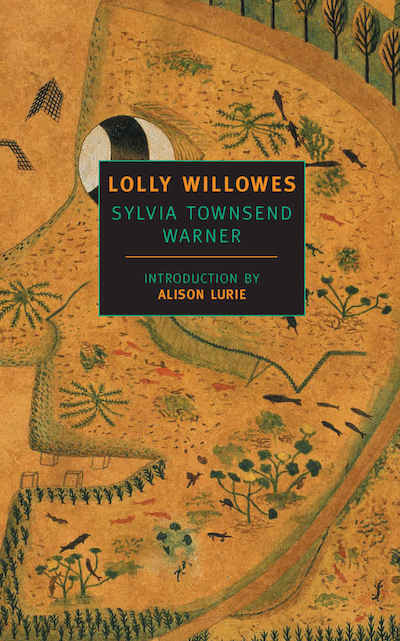

She also attempted a novel, The Quick and the Dead, which was quickly discarded in favor of a new story about a contemporary witch. This novel, which became Lolly Willowes, was far easier for Sylvia to write: “One line led me to another, one smooth page to the next.”

Sylvia was also corresponding with the writer, philosopher, and Dorset recluse Theodore Powys, and her determination to find a publisher for his work brought her into contact with both David Garnett of Nonesuch Press and with Chatto & Windus.

It was Garnett who, in 1923, encouraged her to send her poems for publication, and Chatto that accepted them. The collection was published as The Espalier, followed by Lolly Willowes in 1926.

Both met with great success and Sylvia handled the inevitable questions about black magic and witchcraft with humor and candor, suggesting that modern-day witches might use vacuum cleaners instead of broomsticks for flying.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Dorset and Valentine Ackland

After finishing her second novel, Mr. Fortune’s Maggot, Sylvia’s next project was ambitious: a study of Theodore Powys. She never completed it and only seventy-six drafted pages survive, but the project took her to Dorset and to the village of Chaldon where Powys lived.

There, one summer evening, she met a Mrs. Molly Turpin, also known as Valentine Ackland. Valentine had been renting a cottage in the village since 1925 as an escape from her unhappy marriage to Richard Turpin, and often visited the Powys’s.

This first encounter was not a success. Sylvia felt overawed by Valentine’s poise and beauty (she was almost six feet tall, elegant with a boyish haircut and slim figure) and felt as if she, the “famous novelist,” was a disappointment. She compensated by being dismissive and rude, and Valentine subsequently avoided her in the village.

In October 1927, Sylvia began writing the diary that she would keep for the next fifty years. It shows the busyness and diversity of her London life — often meeting friends (although still avoiding parties), attending concerts and recitals, continuing with her work at the Carnegie project, and publishing her second collection of poetry, Time Importuned, in spring 1928.

By 1929, however, the affair with Buck was fading. Sylvia was beginning to feel old and dowdy: her face annoyed her (“what was wrong with my face was that the orders had been mixed”), and her hair displeased her (“like Disraeli in middle-age, so oily and curly”).

She was also having trouble writing. Her latest novel, Early One Morning, went unfinished and was followed by several false starts. The Tudor Church Music project was wound up, with the final trustees meeting taking place in October. The only thing that she found gave her joy was poetry.

Amid emotion with Buck and worry over Powys’s son Francis, who was said to have consumption, Sylvia traveled down to Dorset in spring 1930. This time she purchased a cottage and, after meeting Valentine again and realizing that she had nowhere of her own in the village, offered her the option of sharing.

The idea was that both women would use the cottage for a month or so at a time, separate and apart, in between London commitments. By the end of the year, however, they had become lovers. Sylvia ended the affair with Buck and left London for Chaldon.

The honeymoon years

Sylvia wrote of those first months, “…life rising up again in me cajoles with unscrupulous power and I will yield to it gladly, if it leads me away from this death I have sat so snugly in for so long…”

Deeply in love, as the months went by their lives “joined up imperceptibly, along all their lengths”. Their worst row was over the housekeeping: Sylvia was accustomed to thrift and to having to be ingenious, whereas Valentine viewed such behavior as unnecessarily alarming and demeaning.

Music, too, was a source of difference, and the concerts and recitals that had been so much a part of Sylvia’s life became rare occurrences. She preferred not to go without Valentine, and Valentine preferred not to go. They both accepted these differences, which gave a little breathing space and privacy between them.

Happy though they were, Valentine was not entirely at ease and often had moments of depression and private drinking — an ongoing problem of which Sylvia remained unaware.

The differences in their writing also caused Valentine some distress. Her reverence for poetry matched her love for Sylvia, and she found her inability to write during the first flush of their relationship a real problem. Sylvia had originally viewed Valentine’s poetry as “pleasing minor verse.”

Now, as Valentine’s lover, she came to see it as superior to her own: lyrical, difficult, with layers that deepened the more she read. However, she also recognized that the short, flowing form would not sell.

Knowing that her own work would be published but that Valentine’s would struggle, Sylvia came up with a plan of sending out their poems together for publication in a single volume, with only their initials on the title page. Valentine agreed, somewhat dubiously. The collection was later published as Whether a Dove or a Seagull, with their full names on the title page of the American edition but no attribution to individual poems. In the English edition, however, a key was included in the back to say who had written what.

Reviews were mixed, with most reviewers becoming too caught up in trying to guess who each poem belonged to rather than to actually review the poems themselves. Valentine was embarrassed and upset.

The shift to Communism and the Spanish Civil War

In the winter of 1933, Valentine began to read political pamphlets. Most of them focused on atrocities in Nazi Germany and the colonial situation in Africa and troubled her enormously, but she was wary of the left-wing alternatives.

By 1934, however, the scale of Nazi brutality in Germany had changed her mind, and even Sylvia — who previously had been generally uninterested in politics — was persuaded that the Communist cause was a just one.

In the spring of 1935, they both became members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and Communism became almost like a blessing on their relationship, which they had come to think of as marriage.

By 1936, the emerging situation in Spain appalled both of them, and Valentine longed to join the miliciana, the female Republican fighters. This never happened, but in September both she and Sylvia were “called up” to work in a Red Cross unit in Barcelona. Their work there only lasted three weeks, but it was enough for Sylvia to develop a passion for Spain that matched her passion for politics.

Through it all, she continued to write. In January 1936 she finished her novel Summer Will Show, and in the spring she also submitted the first of 150 short stories to The New Yorker. After having made a bet that it would be rejected, she had to forfeit her £5. On the whole, though, it was a good bargain; the regular income that followed was to make her financially secure for the rest of her life.

A dangerous affair: Elizabeth Wade White

During 1937 Sylvia became a whirlwind of activity for the Party, undertaking several public speaking engagements. The flurry was in part due to the lingering enthusiasm from Spain, but also as a distraction from one of Valentine’s affairs.

Sylvia always remained faithful to Valentine, but Valentine often had “dalliances” which Sylvia did not mind; indeed, she encouraged them, not wanting Valentine’s desire for her to be tainted by longing for others.

She was always convinced of their love for each other and told Valentine as much, noting that if ever a woman came along who caused Sylvia damage, then her feelings would be very different. Until 1938, she never had cause to test those feelings.

Elizabeth Wade White was a young, rich American who Sylvia had met in 1929 on a short trip to New York. Also a Communist, in 1938 she was on her way to Spain and, after getting back in touch with Sylvia, stayed in Dorset for a few days en route. The worsening situation in Spain made it impossible for her to get there, and she turned back to Paris. Sylvia and Valentine offered her a place to stay, and by November of that year, Valentine and Elizabeth were lovers.

By February 1939, Sylvia was sufficiently unhappy that she considered moving out of the shared house. Valentine begged her to stay, but a joint trip to America for a Writer’s Congress was a disaster. Elizabeth, tagging along, was unwilling to share Valentine and became increasingly possessive and jealous.

Sylvia attempted to conceal how hurt and upset she was, while Valentine was torn between the two of them. After a difficult summer, the news of war made Valentine’s mind up for her. She returned to England with Sylvia, but things remained strained.

Both Sylvia and Valentine volunteered with the local branch of the Women’s Voluntary Service during the war, while Valentine also took on extra clerking duties.

Sylvia continued to write, publishing a volume of short stories in America, But the war years were difficult for both of them, and in 1944 Valentine fell into an almost suicidal depression. She felt she could not write, was worried about money, and felt guilty over their relationship, which had never really recovered from the disastrous trip to America.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

After the war, and another affair

Sylvia continued to write throughout the war, publishing The Cat’s Cradle Book in America and beginning work on a new novel The Corner That Held Them. Both she and Valentine volunteered in the Women’s Voluntary Service. Valentine hated the rigidity of the roles she was given, and by 1944 had fallen into a suicidal depression.

After the war, their lives continued to diverge. Sylvia had more success with her writing, signing a lucrative First Reading Agreement with the New Yorker, finishing The Corner That Held Them, contributing articles to magazines such as The New Statesman and The Countryman, and accepting a commission to write a book about Somerset.

Valentine, meanwhile, was experiencing the private transformation of spirituality and religion, something which Sylvia did not understand or easily accept.

In April 1949, this new preoccupation with God was interrupted when Elizabeth Wade White came to visit again. This time both Valentine and Sylvia realized that Elizabeth would not simply “blow over” and Valentine found herself torn once more.

She was genuinely in love with two people at the same time, but her eventual solution pleased nobody: in an echo of their arrangement before the war, she proposed that they should all three live together, Valentine and Elizabeth as lovers and Sylvia as a companion.

Sylvia, horrified, rejected this idea completely, and began to think of the practicalities of moving out. She continued to live with Valentine while Elizabeth returned to America to make preparations for moving, but, as she said in a letter to her friend Alyse Gregory, “the attrition of waiting is as dangerous as a wound that may turn to gangrene.”

Elizabeth’s arrival date was set for September 2, 1949, for one month. During this time, Sylvia would live in a hotel rather than find another place to live permanently. But while Sylvia found life in the hotel dreary and dull, Valentine struggled to adjust to living with Elizabeth and missed Sylvia desperately.

By spring 1950, when Elizabeth had returned to America, the affair — which had been so much more than an affair — was over, but Valentine and Sylvia’s relationship never fully recovered.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The last years

The mood of the 1950s was uncertain, with the threat of another war looming. Both Sylvia and Valentine continued to support Communism, but with far less zeal than before. In 1953 Valentine formally resigned from the Communist Party and turned to Roman Catholicism.

Sylvia did not share Valentine’s enthusiasm for religion. Their conversation around the church was wary at best, and in private Sylvia found that flippancy was the best way for her to deal with the situation.

The church at Weymouth attended by Valentine became “Our Lady of Winkles,” the prayer sheets “Holy Crumbs,” the devotional candles by Valentine’s bed “blue nightlights”. But the gap opening between her and Valentine disturbed Sylvia a great deal.

She even felt herself to blame, writing to a friend that, “she would not, she could not, have turned back into that church if loneliness, unhappiness, sense of frustration, disappointment, disillusionment, had not driven her.”

Sylvia focused instead on taking joy from other things — the garden, her cats, her writing, the time she spent with Valentine where the Church was not a topic of conversation, music.

In 1954 her latest novel, The Flint Anchor, was published with rave reviews, and later that year she was offered the chance to translate Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve. This was published in 1958 to great critical acclaim and was followed in 1964 by a biography of the novelist T. H. White (published in 1967).

However, Valentine was suffering from serious health problems. During the 1960s she underwent an operation for temporal arteritis and then treatment for breast cancer. After two operations and radiotherapy, it was found that the cancer had spread to her lungs. She died, with Sylvia at her bedside, on November 9, 1969.

In the months afterward, everyday life ceased to have much meaning for Sylvia. Her writing slowed down, and although she kept up correspondences with friends, she felt that nothing could fill the gap Valentine left. Some joy in life was only restored when, in 1972, she befriended the young widow of an Austrian count, Gräfin Antonia Trauttmansdorff.

What started as a superficial social acquaintance grew to a deep friendship that sustained Sylvia through her last years. It was during this time that she wrote Elfindom, saying that her new friendship allowed her to leave behind the intricacies of the human heart and write something entirely different.

Soon Sylvia’s health began to deteriorate due to old age. Having always been strong and robust, she began falling, and by the beginning of 1978 could not walk more than a few steps without support. She died, at home, at the beginning of May, surrounded by the blooming flowers in her garden.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Sylvia Townsend Warner

Major works

Novels

- Lolly Willowes (1926)

- Mr Fortune’s Maggot (1927)

- The True Heart (1929)

- Summer Will Show (1936)

- After the Death of Don Juan (1938)

- The Corner That Held Them (1948)

- The Flint Anchor (1954)

- The Music at Long Verney: Twenty Stories (2001; posthumous)

Poetry collections

- The Espalier (1925)

- Time Importuned (1928)

- Opus 7 (1931)

- Whether a Dove or Seagull (1933; jointly written with Valentine Ackland)

- Boxwood (1957)

- Collected Poems (1982)

More information

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Sylvia Townsend Warner Society

- Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes is ‘a great shout of life’

- Colm Toibin Reads Sylvia Townsend Warner

- Sylvia Townsend Warner Reading Week 2020

Biographies and letters

- Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography by Claire Harman (1989)

- I’ll Stand By You: Selected Letters of Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland, edited by Susanna Pinney (1998)

- This Narrow Place: Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland 1930-1951, by Wendy Mulford (1988)

- The Akeing Heart: Letters Between Sylvia Townsend Warner, Valentine Ackland and Elizabeth Wade White, edited by Peter Haring Judd (Handheld Press, 2018)

Leave a Reply