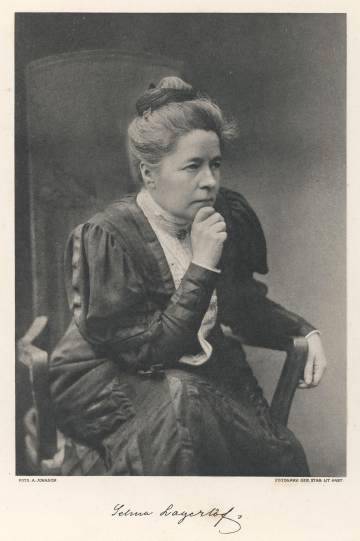

Selma Lagerlöf, First Women Nobel Laureate in Literature

By Marcie McCauley | On March 7, 2020 | Updated August 20, 2022 | Comments (0)

Selma Lagerlöf (November 20, 1858 – March 16, 1940) was a Swedish author who has the distinction of being the first woman ever to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the first Swede to win the award.

She was also an active teacher throughout her professional life and in 1914 became the first female admitted to the Swedish Academy.

Once, when asked for her favorite color, Selma answered, “Sunset.” A suitable answer for a woman who more often chose the thrill of a good story over personal adventure, romanticism over realism, and the pleasures of home over traveling afar.

. . . . . . . . .

Selma in 1881

. . . . . . . . . .

Childhood and early life

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf was born in Värmland, Sweden, in a single-story red house with a tile roof, called Mårbacka. She describes her early years in this “little homestead, with low buildings overshadowed by giant trees” in The Story of a Story (1902) and Memories of My Childhood (1934).

Her father, Erik Gustav, was a retired army officer, who devoted himself to the life of a gentleman farmer, with progressive ideals that were often unrealized. Her mother, Lovisa Elisabeth, was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and mine owner.

When she was three years old, Selma was diagnosed with paralysis. Her parents took her to the seaside town of Strömstad the following summer, on Sweden’s west coast, in hopes of restoring her health.

She continued to improve, and after a winter’s treatment at Orthopedic Institute in Stockholm, when she was nine years old, she could walk more easily. Still, one hip would remain weakened throughout her life.

One of her remarkable experiences in the city was attending the play “My Rose of the Forest” at the Royal Dramatic Theatre. After she returned home to Mårbacka, the children in the family played theatre, building a wall with beds, bureaus, tables and chairs and covering it with blanket and quilts, to create a stage backdrop.

A great reader

Selma read plays, novels, and poetry throughout her younger years; stories were always important to her. Both her grandmother and her Aunt Ottiliana told her stories and, when Selma was old enough, she read aloud to her mother. Her Aunt Lovisa always had a book hidden in her sewing basket.

In the evenings, after knitting and handicrafts were set aside, the family sometimes read aloud Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, One Thousand and One Nights, Esaias Tegnér’s Frithiof’s Saga (1825) or Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s Fänrik Ståls sägner (1848).

While she was staying in Stockholm, Selma read her way through Walter Scott’s fiction, before her tenth birthday.

Her mother and her governess did not allow her to read indiscriminately, however; they withdrew Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1859) at the most exciting part. And, when she was studying for her first communion, The Barber-Surgeon’s Tales (1853-67) by Zacharias Topelius was declared too “worldly” (although it was acceptable afterwards).

Selma did single out one book from her childhood, however:

“For me acquaintance with this Indian story (Osceola) had a decisive effect on my whole life. It awoke in me a deep, powerful desire to produce something as fine. Thanks to this book, I knew as a child that later I should above all love to write novels.”

The novel in question is Osceola the Seminole, or, The Red Fawn of the Flower Land (1858) by Thomas Mayne Reid.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a teacher

Selma’s governess, Aline, had believed that she might have a talent for storytelling, so she encouraged Selma’s aspirations. When Aline’s older sister, Elin, took over the tutoring, however, she did not recognize any exceptional talent in Selma, so she steered her attention elsewhere.

At twenty, Selma took the examination to attend teachers’ college. Harry Edward Maule, in his 1917 biography, Selma Lagerlöf; The Woman, her Work, her Message, described her anxiety. There were forty applicants and only twenty-five opportunities available for study at the Women’s Superior Training College – Selma’s bid was successful.

After her three-year program, 1882 to 1885, at Högre lärarinneseminariet in Stockholm, Selma was appointed to the Grammar School for Girls in Kandskrona, Skane. She worked there for ten years.

One of her pupils, Anna Clara (later Fru Dr Romanus-Alfven), observed that Selma taught everything from Darwinism to Socialism to Utilitarianism and, as Anna Clara, continues, she “never turned us away with the excuse that we were too young to understand.”

Even while absorbed in teaching, Selma intended to write. She was influenced by works in the college library, including Heroes and Hero Worship by Thomas Carlyle (1841), which she first read in the spring 1884, and reread often, admiring its “direct and fine” prose.

Beginning to write

“Before Aline had advised me not to write, I had felt only a vague, intangible longing, but now this longing has become a fixed determination,” Selma wrote in her memoir.

Carlyle’s prose was an inspiration: “I had the distinct feeling, that I also could write such prose – the ability to write thus straight from the heart, to deal freely and unhindered with the reader, to express irony, love and wisdom in imaginative and brilliant language appealed to me as exquisite.”

When she later discovered his History of the French Revolution (1837), she felt the “same feeling of inner kinship.”

She began writing short stories in 1881 and when her father’s health deteriorated as he approached death, Selma wrote to escape her pain. Much of this work found its way into the five chapters she submitted to a writing contest sponsored by the women’s paper Idun in the spring of 1890.

When Selma won first prize, she requested a year’s leave from teaching to complete her novel and, with the tangible support of friends and colleagues, she undertook the project.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a published author

In August 1891, Selma finished what would become her best-known novel, The Saga of Gösta Berling, the story of a demoted minister who comes to stay at a manor in Ekeby. His adventures – and those of the other pensioners and residents there – were published at Christmas (also by Idun) and launched a long and impressive career.

Selma had tremendous confidence in her work, as expressed in a letter written to her mother, April 23, 1891 (translated by Anna Nordlund in a 2004 article in Scandinavian Studies (76.2):

“You see, mother, I have a terribly strong belief in the genius inside me; how else could I write and publish anything? I believe that this is the best book yet in Swedish, and I cannot understand when people talk about its deficiencies and how I will improve.”

A prolific career

Her confidence was warranted. Over the course of her career, she would publish more than thirty works. And Värmland would become synonymous with “Gösta Berling” land — travelers from all over the world would be drawn to visit this part of the continent, intrigued by her fiction.

Walter A. Berendsohn’s 1927 biography, Selma Lagerlöf: Her Life and Work notes that Gösta’s action unfolds between two Christmas Eves and “flows on like a river which here and there expands into a quiet lake.”

The background to all of the adventures is Lake Löven (Värmland’s fictionalized Lake Fryken) and while there’s “no exact parallel” in English literature, “there burns in it the same passionate intensity which glows through the pages of Jane Eyre.”

Selma wrote The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (1906) in response to a request from the Swedish school board. Her second volume of stories about a young boy flying over the countryside on a goose would be published five years later.

When the volumes were translated into other languages, the focus was shifted away from the Swedish geographical details to the stories about the natural world, maintaining their simplicity and charm.

Her trio of novels detailing the life and history of a Swedish family was also very popular. It had been published in three volumes – The General’s Ring (1925), Charlotte Löwensköld (1925), and Anna Svärd (1928) – and, later, would be combined into The Ring of the Löwenskölds (1931).

In a 1931 preface to Berendsohn’s biographical work, Vita Sackville-West describes Selma as “a poet writing in prose,” whose “realism is deliberate, whereas her romanticism (with a vengeance) is instinctive.”

She observes “that she writes always as a woman: not one of her books could have been written by a man. Her art is essentially feminine, not masculine, yet without the slightest consciousness of sex.”

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Recognition and awards, including the Nobel Prize

Selma’s peers were not the only admirers of her work. Following the success of The Saga of Gösta Berling, King Oskar and Prince Eugen gave Selma a traveling scholarship in 1895, to free her from the demands of teaching. She traveled on the continent and in the Near East, and her journeys in Italy, with her friend and companion Sophie Elkan, were particularly influential.

In 1909, Selma became the first Swede and the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. She would also be the first woman, in 1914, to be elected to the prestigious group of eighteen authors and scholars which comprised the Swedish Academy.

Many of her works were made into films after 1919, including a version of her debut novel in 1924 Sweden, Gösta Berling’s Saga, directed by Mauritz Stiller. It starred the young actress Greta Garbo as the Countess Elizabeth and Lars Hanson as Gösta Berling. In 1925, an opera by Riccardo Zandonai would also be produced based on this popular story.

Selma Lagerlöf’s legacy

In her memoir about her childhood in Mårbacka, Selma writes: “When I grow up, I want to live in a house that is painted white and has an upper story and a slate roof; and I would like to have a grand salon where we can dance when we have parties.”

In fact, as soon as she was able to do so, in 1907, she repurchased Mårbacka, which had been sold following her father’s death. With the aid of her Nobel Prize winnings, she was able to finally secure the property in 1910, when she was fifty-one years old.

Thereafter, she wintered in Falun, Dalarna; she spent the rest of the year living on and managing the estate, with its dozens of tenants and a hundred cultivated acres. The homestead now operates as a museum.

In 1911, she addressed the international congress on suffrage in Sweden: “Have we done nothing which entitles us to equal rights with man? Our time on earth has been long – as long as his.” As a young reader, she was moved by stories “about those who have struggled against great odds and who, in the end, have attained success.”

Although her position on suffrage and women’s rights was considered conventional by some, she did recognized social and political injustice and often worked towards change for individuals in need. For instance, the proceeds from the Gösta Berling film were devoted to a “Gösta Berling Fund” dispensed to needy and elderly authoresses.

A documentary film on Selma Lagerlöf was produced by Suntower Entertainment Group (2014), in Swedish, with glimpses of the homestead museum and footage of the author in her later life.

In the same questionnaire, in which she was asked about her favourite colour, Selma was asked to define her favorite quality in a man and in a woman (her answer was the same for both: “Depth and earnestness”) and about her favorite occupation. Her reply – “The study of character” – is still evident in her published works today.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Selma Lagerlöf

Major works

Selma Lagerlöf was incredibly prolific, and her works are too numerous to list here. For a complete list of her works, denoting which have been translated into English, see this listing on Wikipedia.

Selected Biographies

- Selma Lagerlöf: The Woman, her Work, her Message by Harry Edward Maule (1917)

- Selma Lagerlöf: Her Life and Work by Walter A. Berendsohn (1931)

- Selma Lagerlöf I (1942) and Selma Lagerlöf II by Elin Wägner (1943)

- The Critical Reception of Selma Lagerlöf in France by Anne Theodora Nelson (1962)

- Selma Lagerlöf by Vivi Edström (1984)

More information

- Selma Lagerlöf: A Nobel Mind

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Selma Lagerlöf on the Nobel Prize site

- Fourteen-minute video biography in Swedish, including many photographs, and cover images of some of her published works

Read and listen online

Leave a Reply