Muriel Spark, Author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

By Elodie Barnes | On May 16, 2023 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (0)

Dame Muriel Spark (February 1, 1918 – April 13, 2006) was a Scottish novelist, short story writer, poet, and biographer.

Her novels were famous for their wit and style, and several have been adapted for film, television, and the stage. Her best-known work is the 1961 novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

Spark was quite prolific — in a nearly fifty-year career she wrote twenty-two novels, several collections of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction. She has been recognized as one of the greatest British writers.

Early years and education

Muriel Spark was born Muriel Sarah Camberg in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1918. Her father, Bernard, was Jewish and an engineer by profession. Her mother, Sarah, was a music teacher who had been raised Anglican.

She had one older brother, Philip, born in 1912, but the two were never close (with characteristic Spark wit, she once compared him to a Chekhov short story).

The family lived in the largely working-class Edinburgh suburb of Bruntsfield. Later, she would recall her childhood as financially tight but largely happy.

With the help of public bursaries, she went to the James Gillespie School for Girls, and then to a merchant school (much later, she would use this as the model for Marcia Blaine’s in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie).

Muriel was interested in literature from a young age, and at age fourteen won first prize in a poetry competition commemorating Sir Walter Scott’s death a century earlier in 1832.

She signed up to study commercial and precis writing at Heriot-Watt College in Edinburgh, but didn’t go on to university, partly because her parents could not afford it, and partly because, in her opinion, “many older girls who were studying at Edinburgh University were humanly rather dull and earnest, without adult style or charm.” Instead, she studied secretarial skills and later worked in an Edinburgh department store.

A disastrous marriage

In 1937 she met Sydney Oswald Spark, known as “SOS,” in Edinburgh. He was thirteen years older than her, and a teacher about to embark on a three-year stint in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

They married in September of that year and she followed him to Africa. Their son, Samuel Robin (known as Robin), was born in 1938.

Not much is known about this part of her life, and Muriel rarely spoke about it. However, it soon became clear that her husband suffered from manic depression and increasingly experienced violent episodes.

She became more and more unhappy, and left both Africa and her marriage in 1944, initially leaving Robin behind.

Later she wrote: “I was attracted to a man who brought me flowers when I had flu. (From my experience of life I believe my personal motto should be ‘beware of men bringing flowers’.)” She chose, however, to keep her husband’s name: “Camberg was a good name, but comparatively flat. Spark seemed to have some ingredient of life and fun.”

When Robin arrived in London in 1945, she sent him to live with his grandparents in Edinburgh while she set about making a living in London. She took several different jobs, including a stint with the Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, and as editor of the Poetry Society’s magazine, Poetry Review, from 1947 – 1949.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1950s, and conversion to Catholicism

Muriel Spark was also writing and publishing her own poetry. A first collection, The Fanfarlo and Other Verse, was published in 1952, just a year after she had entered a competition run by the Observer newspaper and won (out of almost seven thousand entries) with her poem “The Seraph and the Zambesi”

In the early 1950s, she also worked with literary journalist Derek Stanford on critical studies of Mary Shelley, Emily Brontë, and John Masefield. She edited volumes of Emily Brontë poems, Brontë letters, and Mary Shelley letters.

The strain of living on the margins of literary London — always financially precarious, popping diet pills in place of meals, and never quite knowing what was coming next — began to wear on her, and she suffered an emotional and physical collapse in 1954.

It was also a profoundly spiritual collapse. The year before she had been baptized into the Church of England, influenced heavily by T. S. Eliot and his writing (which, at the height of her breakdown, she believed contained secret messages in Ancient Greek), but now decided to convert to Roman Catholicism.

In her convalescence, she was supported by fellow convert Graham Greene (who sent her money and red wine on the condition that she would never pray for him), while a priest found her the Camberwell bedsit from which she would write her early novels. But she was never able to fully articulate why faith and religion had become so important to her at this point in her life.

“The simple explanation,” she said later, “is that I felt the Roman Catholic faith corresponded to what I had always known and believed; the more difficult explanation would involve the step by step building up of a conviction.”

At the same time as her conversion to Catholicism, her son Robin was embracing Judaism. It caused a family rift when he claimed that his maternal great-grandmother was Jewish and petitioned for her to be posthumously recognized as such.

Muriel retaliated by accusing him of seeking publicity to advance his art career. This dispute, which dug deeply and painfully into family history and heritage, lasted until her death. She took steps to ensure that her son received nothing from her estate.

A rich writing career

Muriel’s conversion to Catholicism profoundly influenced her writing. In a later interview, she said “somehow with my religion – whether one has anything to do with the other, I don’t know – but it does seem so, that I just gained confidence.”

Penelope Fitzgerald, a contemporary and fellow novelist, perhaps put it more succinctly: “…it wasn’t until she became a Roman Catholic … that she was able to see human existence as a whole, as a novelist needs to do.”

The first of more than twenty novels, The Comforters, was published in 1957. It established Muriel Spark’s distinctive voice and received excellent reviews (including those by Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh, who wrote that he preferred The Comforters to his own The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold).

From then until the mid-1970s, she published almost a novel a year, as well as short stories, plays, essays, children’s books, and further collections of poetry.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie: Opposing Reviews

. . . . . . . . . .

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and other novels

What would become Muriel Spark’s best-known novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was published in 1961.

The tale of the middle-aged Edinburgh schoolteacher became legendary. Its success on Broadway, and in film and television versions ensured that Muriel was financially secure for life. The 1969 film starred a young Maggie Smith, and is considered a cinematic classic.

Two other novels were also adapted for film: The Driver’s Seat (1970) starring Elizabeth Taylor and The Abbess of Crewe (1974) starring Glenda Jackson.

Other novels were adapted for television (The Girls of Slender Means published in 1963), for radio (The Ballad of Peckham Rye published in 1960), and for stage (Memento Mori and Doctors of Philosophy).

Escape to Italy

In 1963 Muriel left Britain for good. Mostly, she confessed, it was to escape those friends from whom her sudden success had estranged her. She was particularly keen to avoid Derek Stanford, who had published a conflicted, slightly disturbing memoir of her, based on the years they collaborated.

She moved first to New York, where she worked as a staff writer at The New Yorker. Editor William Shawn was a supporter of her writing, having published The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie in full in one issue of the magazine.

By the time she moved to Rome in 1967, she had invented herself almost as a character in one of her novels: chic, with perfect hair and nails, expensive jewelry and furs. Living in an immaculately decorated apartment just across from the Vatican, she self-styled as the epitome of wit and success.

In 1968 she met Penelope Jardine, a rich young woman studying art in Rome. Together they traveled to Oliveto in Tuscany and settled there to live and work. There they remained until Muriel’s death in 2006. Visitors reported that she was bright, happy, and less worried about dressing well: “There isn’t really a need for it here.” She enjoyed watching TV soaps in bed.

Muriel continued to write, sometimes spinning out stories in a single draft in spiral bound notebooks from the Edinburgh stationers James Thin, using one side of the paper only. Her last novel, aptly (or ironically) titled The Finishing School, was published in 2004.

Critical reception of Muriel Spark’s work

Muriel Spark was always something of a controversial author among certain readers. Her particular brand of waspish Catholic chic was often mistaken for right-wing tendencies, and feminists in particular often distrusted her work. In addition, the brevity of her novels led many critics to dismiss them as light and trivial.

However, more recently, John Lanchester, in his introduction to a Penguin edition of The Driver’s Seat, wrote that she should be viewed more as:

“… proto Post-Modernist, a writer with a sharp and lasting interest in the arbitrariness of fictional conventions; a writer whose eager adoption of the conventions of the novel have always been accompanied by a wish to toy with, subvert, parody, and undermine them.”

In a 2014 essay in The New Yorker, Parul Sehgal wrote of The Girls of Slender Means, “This is Spark’s particular genius: the cruelty mixed with camp, the lightness of touch, the flick of the wrist that lands the lash.”

She was also often referred to, especially during the 1990s, as “the greatest living British writer,” and counted W. H. Auden, John Updike, Tennessee Williams, and Iris Murdoch among her admirers.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Curriculum Vitae: A “clearly disappointing” autobiography

Muriel Spark rarely appeared on television or radio and was notoriously private about her life. This reticence helped to turn her 1992 autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, into the literary event of the year.

However, it was as notable for what it didn’t tell as for what it did. Like most of her books, it was short, and the narrative ended with the publication of her first novel.

Novelist Anita Brookner said that “as an account of a writer’s formation Curriculum Vitae is clearly disappointing,” while biographer Victoria Glendinning remarked that “one cannot tell from this book which people, if any, she loved with a passion.”

On the more positive side, Jenny Turner noted that “Although it skates over many things about which eager beavers may want to know more: Muriel’s disastrous teenage marriage … her twenties in Rhodesia … her son from that marriage … none of this is anybody’s business but Spark’s own.”

Muriel Spark’s legacy

Muriel Spark died on April 13, 2006, and is buried in the cemetery of Sant’ Andrea Apostolo in Oliveto. Her entire estate was left to Jardine, while her personal archive is held at the National Library of Scotland.

During her lifetime she received honorary degrees from universities including Oxford, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, London, and the American University of Paris. She was elected a Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature, and an Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

She was also an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1993.

Today, all of Muriel Spark’s novels remain in print and continue to be popular. In 2008, The Times of London ranked her eighth in its list of the “50 greatest British writers since 1945” and in 2010 she was posthumously shortlisted for the Lost Man Booker Prize of 1970 for The Driver’s Seat.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Muriel Spark

Major works: Novels, short stories, poems, and essays

All of Muriel Spark’s novels are still in print in various editions, including a full set of hardback Centenary Editions published by Polygon (Birlinn) in 2018. Muriel Spark’s list of published works is quite extensive; see her full bibliography.

Biography and criticism

- Curriculum Vitae by Muriel Spark (an autobiography, 1992)

- Muriel Spark: The Biography by Martin Stannard (2010)

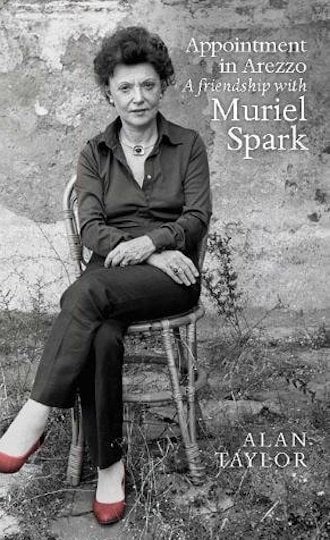

- Appointment in Arezzo: A Friendship with Muriel Spark by Alan Taylor (2017)

- A Good Comb, edited by Penelope Jardine (2018)

More information

- Obituary in The Guardian

- Reader discussions of Muriel Spark’s books on Goodreads

- The Best Books by Muriel Spark

- Jewish Women’s Archive

- Wikipedia

Leave a Reply