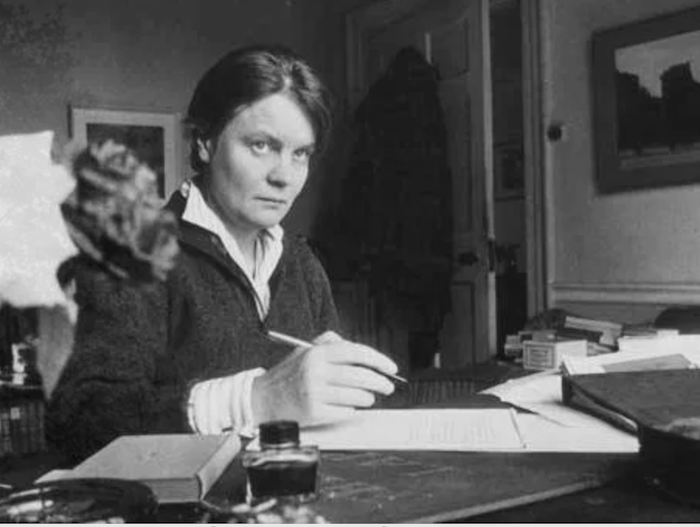

Iris Murdoch, British Novelist and Philosopher

By Taylor Jasmine | On October 24, 2019 | Updated April 26, 2024 | Comments (0)

Dame Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919 – February 8, 1999), the prolific British novelist, philosopher, and playwright was a master of blending psychological depth and dark humor into her fiction and nonfiction works.

Born Jean Iris Murdoch in Dublin, Ireland, her father was a World War I veteran and civil servant. Her mother was a former singer. When Murdoch was a newborn, her family moved to London so her father could take a British government position. She remained an only child.

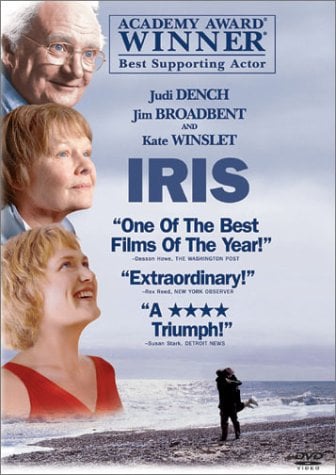

The 2001 Academy Award and BAFTA Award-winning film Iris is based on her life and marriage to John Bayley, a writer and English professor, and her struggles with dementia.

In a 1990 interview with The Paris Review, Murdoch praised her family as a “felicitous trinity” though she knew her mother gave up singing professionally for marriage.

She also said, “I knew very early on that I wanted to be a writer. I mean, when I was a child I knew that.” Recognition that her mother’s ambition was subsumed to the time’s gender norms likely fueled Murdoch to achieve.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Iris Murdoch biography highlights

• Her family immigrated from Ireland to Great Britain shortly after her birth. Her academic gifts established her as an intellectual of note. She toured Europe in service to the British Treasury Department and a shuttered United Nations branch once dedicated to relief work.

• Murdoch met John Bayley at Oxford, and they married in 1956. She defied convention and chose not to have children. Her visible career, use of her maiden name and publicized open marriage made Murdoch a symbol of progressive womanhood for contemporary feminists.

• While at university, Murdoch came into brief but influential contact with prominent thinkers like Jean Paul-Sartre and Wittgenstein. Later, she was romantically linked to the Nobel Prize-winning author Elias Canetti.

• She received the Booker Prize for her novel The Sea, The Sea (1978). That and several of her other novels were adapted to film.

• Murdoch became afflicted with Alzheimer’s. She slipped into relative reclusiveness but continued to write. She died in Oxford, England, in 1999.

A life of learning and letters

Early academic prowess set the stage for Murdoch’s impressive career. She attended boarding school in Bristol, then studied the classics and philosophy at Somerville College, Oxford, and Newnham College, Cambridge.

She turned down the chance to study at Vassar College in upstate New York out of allegiance to the Communist Party of Great Britain. In The Paris Review interview referenced above, she described how her ambitions were derailed by World War II:

“When I finished my undergraduate career I was immediately conscripted because everyone was. Under ordinary circumstances, I would very much have wanted to stay on at Oxford, study for a Ph.D., and try to become a don. I was very anxious to go on learning.

But one had to sacrifice one’s wishes to the war. I went into the civil service, into the Treasury where I spent a couple of years. Then after the war I went into UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Association, and worked with refugees in different parts of Europe.”

Murdoch met John Bayley at Oxford. The two married in 1956. She defied convention by remaining childless. Her successful career, use of her maiden name, and publicized open marriage made Murdoch an unwitting symbol of progressive womanhood for second wave feminism.

While at university, Murdoch came into brief but influential contact with prominent thinkers like Jean Paul-Sartre and Wittgenstein. Later, she was romantically linked to the Nobel Prize-winning author Elias Canetti.

She later lectured in philosophy at St. Anne’s College, Oxford. Murdoch’s brief dedication to Communism complicated her visits to the U.S. even after she left the party.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: Steve Brodie

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes and literary import of Murdoch’s works

Murdoch bloomed as a novelist in her mid-thirties. After she published several nonfiction works, including the first scholarly text written in English on Jean-Paul Sartre (Romantic Rationalist, 1953), she wrote Under the Net (1954). This first novel set Murdoch on the path to writing twenty-five more.

Murdoch’s acclaim for fiction eclipsed appreciation of her philosophical work. However, her novels’ precise psychological character studies and fixation on moral responses in cerebral plot lines alluded to her philosophical training.

In an appreciation of Iris Murdoch in the New York Times’ Enthusiast column, Susan Scarf Merill suggests where to start as a newcomer to her works:

“The Severed Head [Murdoch’s fifth novel] is an excellent place to start. Married man with mistress discovers wife is leaving him for their psychoanalyst.

Everyone is so concerned for everyone else — husband and wife help each other move, the analyst’s sister (also his lover, it turns out) sticks her nose in everywhere, and by the end, each character has a new partner and it seems that the world has reshuffled into better order, at least for the moment. Madcap as it sounds, it’s calm on the page. Murdoch’s prose is elegant, validating itself by its own certainty.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

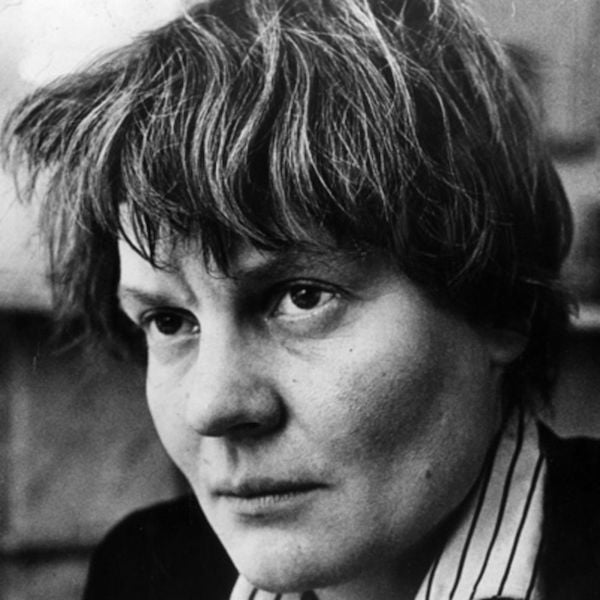

Relationship with Brigid Brophy

The relationship between Iris Murdoch and Brigid Brophy began in 1954. They met at the Cheltenham Festival prize awards, at which Murdoch came second to Brophy. The two writers quickly became close. From this site’s biography of Brigid Brophy:

Murdoch’s biographer Peter Conradi wrote that “the friendship grew when the Leveys visited the Bayleys [Murdoch and her husband John Bayley] at Steeple Aston, and Murdoch saw both in London; for years Brophy and Murdoch would go away for a weekend break. Neither husband felt excluded…”

Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley, was also aware of her extramarital affairs, although she kept the details secret. During the years of their relationship, Murdoch wrote a thousand or more letters to Brophy, some of which are collected in the book Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch 1934-1995.

Awards and Honors

Murdoch is one of the most decorated British novelists of all time. Some of her honors include The Booker Prize for The Sea, The Sea (1978), the Whitbread Literary Award for Fiction for The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974), and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Black Prince (1973).

She received the Booker Prize for her novel The Sea, The Sea (1978).

Several of her novels were adapted to film. Her novels The Bell (1958), A Severed Head (1961), An Unofficial Rose (1962) and The Sea, The Sea were adapted to television series or films.

She received honorary membership to both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1987, she was appointed a Dame of the British Empire.

Final years and Alzheimer’s

Murdoch became afflicted with Alzheimer’s. She slipped into relative reclusiveness but continued to write. Her last novel, Jackson’s Dilemma (1995), was appreciated for how its simple language and lack of hard editing deterred from Murdoch’s signature style, but demonstrated the effects of Alzheimer’s on creativity.

John Bayley documented Murdoch’s later life struggles in his 1999 memoir Elegy for Iris. Her New York Times obituary reported that Bayley was at his wife’s bedside when she died at the age of 79 in Oxford, England, in February 1999.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Iris (2001 film) and cultural resurgence

Actress Kate Winslet portrayed a young Murdoch to Dame Judi Dench’s older Murdoch in the 2001 biopic Iris. The film focused on Murdoch’s youthful intellectual prowess and complicated marriage.

Jim Broadbent, who played John Bayley, received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance. Dench won a BAFTA Award for Best Actress for hers. The film introduced Murdoch to a new generation of literary enthusiasts and fans.

In 2019, The Guardian ran a retrospective marking the reissue of all twenty-six of her novels in what would have been the year Murdoch turned 100. The article called her invented people “shapeshifters,” and praised her abilities to confront “the terrifying truth that human beings, in the absence of God, are off the leash.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Iris Murdoch

On this site

Major Works

The source for this bibliography is Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Kingston University, U.K.:

Fiction

- Under the Net (1954)

- The Flight from the Enchanter (1956)

- The Sandcastle (1957; short stories)

- Something Special (1957)

- The Bell (1958)

- A Severed Head (1961)

- An Unofficial Rose (1962)

- The Unicorn (1963)

- The Italian Girl (1964)

- The Red and the Green (1965)

- The Time of the Angels (1966)

- The Nice and the Good (1968)

- Bruno’s Dream (1969)

- A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970)

- An Accidental Man (1971)

- The Black Prince (1973)

- The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974)

- A Word Child (1975)

- Henry and Cato 1976)

- The Sea, the Sea (1978)

- Nuns and Soldiers (1980)

- The Philosopher’s Pupil (1983)

- The Good Apprentice (1985)

- The Book and the Brotherhood (1987)

- The Message to the Planet (1989)

- The Green Knight (1993)

- Jackson’s Dilemma (1995)

Philosophy

- Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953)

- The Sovereignty of Good (1970)

- The Fire and the Sun (1977)

- Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (1992)

- Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (1997)

Plays

- A Severed Head (with J.B. Priestley, 1964)

- The Italian Girl (with James Saunders, 1969)

- The Three Arrows; The Servants and the Snow (1972)

- The Servants (1980)

- Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986)

- The Black Prince (1987)

Poetry

- A Year of Birds (1978; revised edition, 1984)

- Poems by Iris Murdoch (1997)

Biographies and memoir

- Elegy for Iris by John Bayley (1998)

- Iris Murdoch: A Life by Peter J. Conradi (2002)

- Iris Murdoch: As I Knew Her by A.N. Wilson (2003)

- Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch by John Bayley (2012)

- Iris Murdoch: A Centenary Celebration by Miles Leeson (2017)

More information and sources

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of Iris Murdoch’s works on Goodreads

- 1990 interview in The Paris Review

- Iris Murdoch at 100 in The Guardian

- Iris Murdoch archive at the National Archive, UK

- The Secrets of Iris Murdoch’s and John Bayley’s Unconventional Marriage

Leave a Reply