Margaret Landon, author of Anna and the King of Siam

By Marcie McCauley | On September 9, 2021 | Updated August 20, 2022 | Comments (0)

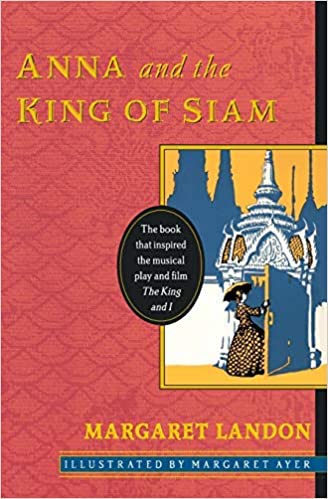

Famed for Anna and the King of Siam (1944), which inspired a variety of adaptations, including the musical “The King and I,” American writer Margaret Landon (September 7, 1903 – December 4, 1993) spent more than a decade studying Siam (now Thailand) and a lifetime writing about it.

Anna and the King of Siam was Margaret Landon’s crowning achievement. It sold over one million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages.

Based on the true story of Anna Leonowens, who served as governess to the King Mongkut, in the 19th century, it introduced Western readers to a world of Asian culture.

Family and Childhood

Margaret Dorothea Mortenson was born in Somers, Wisconsin. Her father, Annenus Duabus Mortenson, was born in Racine, Wisconsin to a Norwegian mother and a Danish father. As a young man, he worked as an office manager in advertising for Curtis Publishing Company in Chicago and, later, in the business department of the Saturday Evening Post.

Her mother, Adelle Johanne Estberg, was born in Franksville, Wisconsin to Danish parents. She didn’t work outside the home until after her husband died in 1925. She then began working as a secretary at a college.

Annenus and Adelle married in 1902 and, after Margaret, had two more daughters: Evangeline, two years younger than Margaret, and Elizabeth, seven years younger.

The Gift of Words

Margaret attended Evanston Township High School in Illinois. Her English teacher there once told her: “You have the gift of words. Do something with it!”

She was also interested in sports, and later served as captain of the women’s baseball, basketball, and tennis teams at Wheaton College, a Christian school in Wheaton, Illinois.

After graduating in 1925, she taught English and Latin in Bear Lake, Wisconsin, an experience she described as “an agonizing year” having “soon discovered that I disliked teaching.”

In1926, she married Kenneth Perry Landon, whom she’d met at college. He was a seminary student, a graduate of Wheaton College and subsequently, Princeton Theological Seminary. The following year he went to Siam, to work as a Presbyterian missionary accompanied by Margaret.

In Siam

After spending most of 1927 and 1928 in Bangkok, where they learned Siamese, the Landons were stationed at Nakhon Si Thammarat and, afterwards, Trang.

Kenneth earned his master’s degree at the University of Chicago in the 1931-1932 academic year but, otherwise, from 1927 to 1937, their missionary work in Siam was all-consuming. Often the Landons were the only non-Siamese people in their environs.

Margaret served as principal of Trang Christian school for girls at her husband’s mission for five years, according to her Washington Post obituary.

While living in Siam, the couple had three children: Margaret Dorothea, William Bradley II, and Carol Elizabeth. These children learned Siamese before they learned English and were issued passports there. After the couple returned to America, they had one more son, Kenneth Perry, Jr.

It’s understandable that Margaret found little time to write anything beyond the mission newsletter and correspondence but, while in Siam, in 1930, she discovered the story which inspired the novel she would write after the family returned to America.

A family friend, Dr. Edwin Bruce McDaniel, had copies of two books written by Anna Leonowens, a widowed woman who describes traveling from Wales to Siam in 1862—both to teach English to King Mongkut’s many children and his favored concubines and to present Western political ideologies.

Both these volumes—The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) and The Romance of the Harem (1872)—were viewed by the Siamese government as disrespectful to the regent and thus banned. Even after the King’s son, Prince Chulalongkorn, became King and abolished the custom of prostration before superiors in the court and freed his slaves (both acts evidence of Leonowens’ influence, she asserted), Anna’s books remained forbidden. But Margaret found her story fascinating.

. . . . . . . . . .

Kenneth and Margaret Landon and their children

. . . . . . . . . .

Return to America, and writing

Back in America, Margaret finally found her own copies of Leonowens’ books, when she visited second-hand bookstores in Chicago. One of her assignments in the night school classes she attended in 1937–38, at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in Evanston, Illinois, reflected her ongoing interest in the widow’s life story.

Her first published work was a magazine article titled “Hollywood Invades Siam,” inspired by Leonowens’ writing, for which Margaret was paid fifteen dollars.

She began writing Anna and the King of Siam in 1939 in Richmond, Indiana, where her family lived until 1942, when Kenneth began working for the State Department as a southeast Asia specialist in Washington D.C. Kenneth would publish three books himself, all on southeast Asia, as well as numerous articles. In addition, he lectured nationally.

Margaret’s close friend from college, Muriel Fuller, who worked in the publishing industry, encouraged Margaret to combine and rewrite the stories in Leonowens’ books, to reduce the lengthy descriptions and refine the timeline. In July 1943, just a few hours before Kenneth Jr.’s birth, Margaret finished her book.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The Road from Siam to Publication

Margaret rewrote some sections of her book as many as twenty times, and her research was meticulous, assisted by her husband’s connections in the State department. Nonetheless, while exploring the story, she didn’t have access to overseas archives and was primarily dependent upon Anna’s published versions of events.

Although two publishers rejected Margaret’s finished manuscript, John Day Company was encouraged by Kenneth Landon’s conversations with key figures there to accept it for publication. John Day had been founded in 1926 by Edwin Walsh, who was married to the novelist Pearl S. Buck. Her writing, including the best-selling The Good Earth (1931), had demonstrated the marketability of western writers’ narratives about Eastern lives.

As biographer Alfred Habegger observes, however, the editor of the publishing house’s monthly magazine (Asia and the Americas) was concerned about the work’s tone. Editor Elsie Weil worked with Margaret to prepare select chapters for publication in the firm’s magazine.

Weil felt it smacked “a little too much of juvenile Sunday school literature.” In fact, Margaret had relied on Anna’s published children’s stories for particular scenes; she also remained committed to Anna’s “deep religious feelings” and believed they were essential to the story.

Walsh instructed Margaret: “Stick as closely as possible to recorded facts. But no doubt you have to invent or reconstruct in many places.” What Weil called the “fictionizing” of the piece was a way to engage readers but, ultimately, the work was published as a biography.

As time passed and more complex Eastern stories were made available to Western readers, Margaret’s imaginative flair would come to overshadow her scholarly intentions. Margaret dedicated the book to her younger sister Evangeline, who had been killed in a car crash in 1941. The book became a best-seller and was also distributed to WWII troops in an Armed Services Edition.

. . . . . . . . . .

Cover of the original UK edition

See also: Revisiting Anna and the King of Siam

. . . . . . . . . .

Later work

Margaret struggled to continue writing. In 1946, a serious bout with rheumatic fever interfered with her work for two years. She published Never Dies the Dream in 1949, a novel, also with substantial detail about Siamese life.

The story told of a missionary running a school in Bangkok in the 1930s, whom Habegger describes as an “honest, idealistic, white American woman”—but it wasn’t as successful as The King and I.

Staying with her perceived expertise, Margaret shifted to non-fiction and began compiling a textbook for high school students on Southeast Asian history.

According to her Washington Post obituary, Margaret’s poor health and family responsibilities are cited as reasons for her slowed writing output. She is described as having “entertained foreign dignitaries” and being a member of “such groups as the Literary Society.” Her textbook, Pageant of Malayan History, remained unfinished.

Death and Legacy

Landon died after a stroke on December 4, 1993 in Alexandria, Virginia, in the Hermitage Retirement Home. Her husband had died there earlier that year, and the couple are now buried together in Wheaton Cemetery in Illinois.

The original manuscript of Anna and the King of Siam and related material is housed in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

The rest of the Landons’ papers are in the Special Collections Department of Wheaton College. Personal papers, correspondence, other manuscripts, and dozens of CDs of oral history interviews with Margaret and Kenneth fill 348 boxes there.

Anna and the King of Siam sold over one million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages. Through Landon’s work, many Westerners who lacked experience with Eastern culture and society gained some understanding.

It seems unlikely that Leonowens’ memoirs would have remained available without Landon’s interest in her life and work. Biographer Susan Morgan notes that Margaret’s novel “introduced Thailand, which is to say, Margaret and Ken’s vision of Thailand, to the American people.” And it further inspired retellings on film, stage, radio and television.

The best-known adaptation was the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I, which opened on Broadway on March 29, 1951. It starred Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner,

The show had a budget of $250,000, which was the largest Rodgers and Hammerstein production at the time. It continues to charm audiences and is regularly and enthusiastically revived on stages around the world. As recently as 2015, a Broadway revival won a Tony Award.

The 1956 film based on the musical, with Deborah Kerr playing Anna, with Yul Brynner reprising his stage role as the King, was tremendously popular and critically acclaimed. Also titled The King and I, it was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won five. Songs like “Getting to Know You” and “Shall We Dance” wound their way into repertoire albums for decades to come.

There were several other film and television adaptations both before and after the stage and screen versions, none as successful or iconic.

Just as Anna Leonowens transformed her personal history and reinvented herself through the narratives she published during her lifetime, Margaret Landon reimagined Anna’s life on the page. Others reimagined those stories on the stage and screen. Multiple interpretations of compelling stories remind us of the power of narrative to open us, as readers, to new worlds of experience.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Margaret Landon

On this site

Marching Through the Years: Revisiting Anna and the King of Siam

Major works

- Anna and the King of Siam (1944)

- Never Dies the Dream (1949)

Stage and film adaptations

- Anna and the King of Siam (1946 film)

- The King and I (1951 stage musical)

- The King and I (1956 film musical)

- Anna and the King (1972 TV series)

- The King and I (1999 animated film musical)

- Anna and the King (1999 film)

More information

- Margaret and Kenneth P. Landon Papers at Wheaton College

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- New York Times Obituary

Leave a Reply