Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Harlem Renaissance Writer

By Nava Atlas | On July 20, 2019 | Updated November 29, 2024 | Comments (0)

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (July 19, 1875 – September 18, 1935) was an American poet, essayist, short story writer, journalist, columnist, and activist.

Through various genres, Alive advocated for the rights of women and people of color. She’s often considered one of the significant writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s, though a good portion of her work predates this era.

Born Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans, she was of Creole heritage, blending African, Creole, European, and Native American roots. Her mixed ancestry gave her a broad perspective on race as she matured, while she personally struggled with the issue of belonging.

Her father, Joseph Moore, a freed slave, was a merchant marine, and her mother, Patrica Wright, was a seamstress. Her family was considered middle class, so she was able to benefit from growing up in a diverse city, fairly free from the constraints of Jim Crow laws.

Alice graduated from Straight University (now Dillard University) in 1892. This was notable for its time, as less than 1% of all Americans were college graduates, let alone women and people of color. Her first job was as a teacher in New Orleans’ public school system. Subsequently, she worked in a variety of occupations, most notably in journalism as an editor and columnist.

Early publications

Violets and Other Tales, her first book, was a collection of poetry, essays, and short stories. Just twenty at the time of its publication in 1895, Alice’s writings were already flavored with feminism and social justice.

Critics have noted the uneven quality of her writings, even as some of the earlier pieces showed her promise as a writer. She wasn’t easy to pigeonhole, which made publishing her work a challenge. Sheila Smith McCoy wrote:

Dunbar-Nelson continued to write and, in 1899, published The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories, which included a revision of “Titee” (one with a happier ending), “Little Miss Sophie,” and “A Carnival Jangle.” Aside from the ending of “Titee,” the revisions of these stories heralded the problems that she faced with later manuscripts.

Publishers, eager for dialect stories such as those that made Paul Laurence Dunbar famous, opted for versions of these stories in which the characters spoke with pronounced creole dialects. Dunbar-Nelson’s published fiction dealt exclusively with creole and anglicized characters; difference was characterized not in terms of race, but ethnicity.

Many of her manuscripts and typescripts, both short stories and dramas, were rejected when Dunbar-Nelson explored the themes of racism, the color line, and oppression. This, coupled with the fact that Violets and St. Rocque, published so early in her career, were, until recently, the only published collections of her work, have made it difficult for both readers and critics to access Dunbar-Nelson’s work.

. . . . . . . . .

A selection of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s poetry

. . . . . . . . .

A very public and disastrous marriage

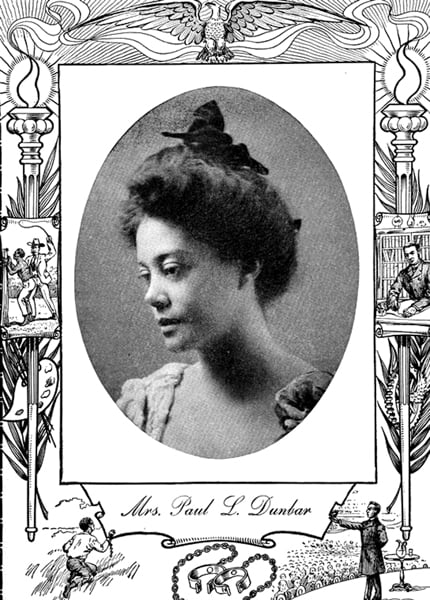

What began as a romantic liaison with Paul Laurence Dunbar soon turned into a disastrous marriage. Dunbar was at the peak of his career when he began courting Alice, while she was at the start of hers. He began writing to Alice after seeing a photo of her with a poem she had published in an issue of Monthly Review in 1897.

They conducted their relationship mainly via correspondence. They met and became engaged, during which time Dunbar raped Alice brutally while inebriated.

Working assiduously to gain Alice’s forgiveness, they married secretly in 1898 in New York City. The couple then moved to Washington, D.C. It wasn’t unusual for women to marry their rapists and seducers. Once the word got out, as it did in Alice’s case, they were considered “damaged goods.”

Dunbar was a revered poet, and one of the most famous African-Americans of his time. But he was also in poor health, an alcoholic, and suffered from a form of tuberculosis.

Alice was bisexual, and it has been posited by Lillian Fadiman, author of Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America, among others, that Dunbar was angered by her affairs. However, this was no excuse for the abuse that he heaped on her.

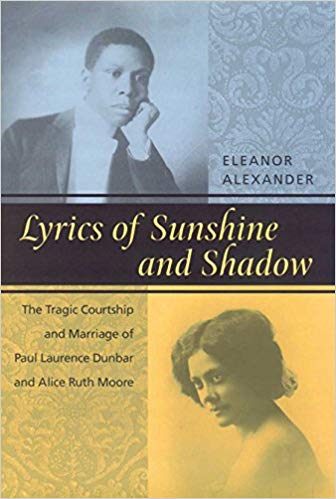

Interestingly, her bisexuality is absent from the book on their relationship, Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow: The Tragic Courtship and Marriage of Paul Laurence Dunbar and Alice Ruth Moore by Eleanor Alexander (2001). The Dunbars seemed like an ideal, charmed couple, with the story of their romantic courtship and elopement widely known.

In 1902, four years into their marriage, Dunbar beat Alice so brutally that she almost died of her injuries. Eleanor Alexander wrote in the book’s introduction:

The Dunbars’ bittersweet romance vacillated between ‘days that were delightful beyond compare … and a dog and cat existence,’ wrote Alice. While that brutal night of January 25, 1902 was not the first time that Paul had physically assaulted Alice, she made certain it was the last. She refused to see him again. For two years he wrote her letters of love, contrition, and news. Alice answered only once, and in one word: “No!”

After leaving her husband, Alice moved to Wilmington, Delaware. She never saw Paul again, and despite the acrimonious ending, never formally divorced him and continued to publish under the name Alice Dunbar. There, she resumed her career in education, teaching in a high school as well as at the State College for Colored Students (Delaware State College) and Howard University.

When Paul Dunbar died in 1906, Alice found out about it the same way most others did — by reading about it in a newspaper.

Coming into her own

Alice married Henry Arthur Callis, a physician, in 1910. This marriage, too, was short-lived. In 1916, she married Robert J. Nelson, a civil rights activist, who may have been the catalyst, at least in part, for her increasing involvement with social justice issues, primarily racial equality and women’s rights. This marriage endured, and Alice continued to have intimate relationships with women as well.

Alice, like her husband, became politically active, and in the early 1920s, campaigned for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (which was ultimately unsuccessful, because of a racist congress). She also helped establish several schools for African-American girls.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A poet, essayist, and columnist

While teaching in Wilmington, Alice continued to publish poetry and essays and served as an editor for African-American periodicals and anthologies. Her poems were widely published in The Crisis (NAACP), Ebony, Topaz, and Opportunity (Urban League) in the late ‘teens and through the 1920s.

This was a remarkably productive period. Alice was right in the thick of the creative flowering of the Harlem Renaissance era, though she didn’t live in New York City, where much of the action was taking place.

Alice was committed to journalism in the 1920s, contributing highly regarded columns, articles, and essays to several prominent Black newspapers as well as magazines and academic journals. She also became a sought-after lecturer and speaker.

While she achieved an unusual degree of success in journalism, it was no easy path for a woman of color, and yet she wrote honestly the obstacles she faced personally and professionally.

In her searingly honest essays, Alice revisited the challenges of growing up mixed-race in Louisiana. She explored these themes along with the varied and complex issues faced by women of color in both her essays and in her body of short stories.

In “Brass Ankles Speaks,” for example, she wrote about multiracial people bearing “the hatred of their own and the prejudice of the white race.”

As her reputation grew, she continued to explore sexism, racism, work, sexuality, and family in the various genres in which she wrote.

In a review in the San Francisco Examiner of Gloria T. Hull’s 1988 book Color, Sex, and Poetry (Indiana University Press), Melanie Lawrence wrote:

“Dunbar-Nelson was ver much her own person, a bright, commanding, and charming generalist who ‘produced literature,’ as she termed it, ranging from serviceable poetry to lively syndicated columns to the diary that Hull thinks best displays her gift for evocative writing …

Dunbar-Nelson comes across as both vivid and ambiguous: a passionate defender of black equality and black women, who shied away from writing directly from her own experience, an elegant lade and a not-so-closeted bisexual, a tireless civic and political organizer.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Brass Ankles Speaks”: Alice Dunbar-Nelson on Growing up Multiracial

. . . . . . . . .

Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s Legacy

Gloria T. Hull, editor of The Works of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (Oxford University Press, 1988), wrote of her subject:

“One senses in practically everything that Alice Dunbar-Nelson wrote a driving desire to pull together the multiple strands of her complex personality and poetics …

What she was able to achieve in prose outweighs her poetic accomplishments although, ironically, being taken as a poet has helped immensely to keep her reputation alive. Dunbar-Nelson was not driven to write poems and did not focus on the genre …

By and large, Dunbar-Nelson’s poetry is what it appears to be—competent treatments of conventional lyric themes in traditional forms and styles. Her signature poem, “Violets,” is the apogee of this type. A few others stand out for various reasons. “I Sit and Sew,” wherein a woman chafes at her domestic role during wartime, seems feminist in spirit.

“You! Inez!” appears to be a rare eruption in verse of Dunbar-Nelson’s lesbian feelings. “Communion” and “Music” were probably (like “Violets”) selections in a no longer extant Dream Book commemorating her illicit affair with Emmett J. Scott, Jr. “To Madame Curie” and “Cano—I Sing” are strikingly well-executed … “The Proletariat Speaks” reminds one of her consciousness about difference and class contrasts.

Dunbar-Nelson, in her way, helped to create a black short-story tradition for a reading public conditioned to expect only plantation and minstrel stereotypes. Her strategy for escaping these odious expectations was to eschew black characters and culture and to write, instead, charming Creole sketches that solidified her in the then-popular, ‘female-suitable’ local color mode.”

Later in life, Alice moved to Philadelphia with her husband when he went to work for the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission. Her health began to decline, and she died in a Philadelphia hospital on September 18, 1935, at the age of sixty.

More about Alice Dunbar-Nelson

On this site

- A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson

- Early Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson (from Violets and Other Tales)

- “Brass Ankles Speaks”: Alice Dunbar-Nelson on Growing up Multiracial

- “Violets” – a short story from Violets and Other Tales

Major works

- Violets and Other Tales (1895)

- The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899)

- Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (1914; in the capacity of editor)

- Mine Eyes Have Seen, (1918; one-act play)

- “From a Woman’s Point of View” (later, ”Une Femme Dit”; column for the Pittsburgh Courier, 1926)

- “I Sit and I Sew,” “Snow in October,” and “Sonnet,” in Caroling Dusk:

An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets (1927) - “As in a Looking Glass” (1926–1930; column for Washington Eagle newspaper)

- ”So It Seems to Alice Dunbar-Nelson” (1930; column for the Pittsburgh Courier)

Biographies and critical anthologies

- Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Gloria T. Hull, editor (1984)

- The Works of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Gloria T. Hull, editor (1988)

More information and sources

- Wikipedia

- Poetry Foundation

- Modern American Poetry

- An Unsung Legacy: The Work and Activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson

- Georgetown University: Classroom Issues and Struggles

- Women Writers You Should Know

- This Harlem Renaissance Writer Seemed to Live an Ordinary Life

- Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson on BlackPast

- Biography of Alice Dunbar-Nelson on ThoughtCo.

Leave a Reply