Learning to See: A Novel of Dorothea Lange by Elise Hooper

By Nava Atlas | On January 26, 2019 | Updated April 16, 2022 | Comments (0)

Dorothea Lange‘s influential photography has been collected and displayed in museums and institutions everywhere, yet few know the story of how Dorothea Nutzhorn became Dorothea Lange, social justice activist and pioneering photojournalist. In Elise Hooper’s much anticipated second novel, Learning to See, Dorothea Lange’s legacy is reimagined in a riveting new light.

In 1918, a fearless 22-year-old arrives in San Francisco with nothing but a friend, her camera, and determination to make her own way as an independent woman. In no time, Dorothea goes from camera shop assistant to celebrated owner of the city’s most prestigious and stylish portrait studio.

At a time when women were supposed to keep the home fires burning, Dorothea was forging her own path and gaining popularity while doing it.

Shortly after finding her own success, she meets the talented but volatile painter, Maynard Dixon, and becomes his wife. Their early days are colored by their blissful Bohemian lifestyle and mutual artistic inspiration. But by the early 1930s their marriage mirrors the collapse of the American economy and Dorothea must find ways to support her two young sons single-handedly.

As her personal life implodes, she becomes more determined than ever to expose the horrific conditions of the nation’s poor. Taking to the road with her camera, Dorothea creates images that would go on to inspire, reform, and define the era.

Then, when the United States enters World War II, Dorothea chooses to confront the incarceration of thousands of innocent Japanese Americans.

Her ambition and refusal to turn away from the injustices of the world shape her entire catalogue of work, and Learning to See spans the decades of this tumultuous era of American History. Elise Hooper provides a gripping account of the unwavering woman behind the camera who risked everything for art, activism, and love, even when her choices came at a steep price. (— from the publisher)

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

A Conversation with Elise Hooper, Author of The Other Alcott

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Why did you decide to write about Dorothea Lange?

A: After I finished writing The Other Alcott, I decided to be practical and find a new story set closer to home. I’d always found Oregon-born Imogen Cunningham’s abstracted flower photographs to be beautiful and wanted to learn more about her.

During my research, I discovered that her best friend, Dorothea Lange, had also been a pioneering photographer, although the women had very different views on the purpose of art and photography.

When I learned Lange had photographed the internment of Japanese Americans and that these photos had been impounded due to their subversive points of view, I decided to shift my focus from Cunningham to her best friend, Lange.

In the Pacific Northwest where I live, the internment’s legacy is particularly relevant since many of Seattle’s residents were forced to leave their homes and businesses after FDR issued Executive Order 9066.

I wanted to know more about this woman who dared to believe the government was making an unconscionable mistake at a time when some Americans actively participated in discrimination against Japanese Americans or looked the other way.

Midway through writing this novel, the political climate of the United States shifted with the results of the 2016 presidential election. Women took to the streets in January 2017 to express many grievances over the direction of the nation’s policies and values.

This energy and rising political consciousness made me believe Dorothea Lange was more relevant than ever since she was a woman who had experienced a political awakening in her late thirties and acted on it.

As a result of the worsening economic conditions in California and the breadlines threading down the sidewalk underneath her studio window in the 1930s, she became an activist for democratic values and social justice.

Though she sometimes denied any political angle to her art, she often spoke about her desire for her work to prompt conversations about labor, social class, race, and the environment. Her awakening as an activist breathed new life into this project for me and made me more excited than ever to tell her story.

. . . . . . . . .

Migrant Mother (1936) is Dorothea Lange’s most iconic photograph

. . . . . . . . .

Q: It’s interesting that a woman who is best known for taking such poignant images of women and children had such a conflicted family life.

A: Dorothea’s complex and seemingly contradictory feelings about motherhood fascinated me. Her own father abandoned her family when she was twelve, and this left her with a powerful sense of rejection. So deep was her hurt that she rarely spoke of it to anyone. In fact, it wasn’t until after her death that Paul Taylor learned the truth of her father’s absence in her life.

Yet despite the anguish that her father’s abandonment caused her, she fostered her own sons out during the Great Depression, a choice for which her children never forgave her.

No one faulted Maynard and Paul for not attending to their children, but people questioned Dorothea’s choices and this criticism stung her. Her ambitions and talents put her at odds with many of the norms of the time when few women were the breadwinners in their families.

So, although she sometimes felt guilty and selfish, she persevered with work she believed was necessary and important. This tension between ambition and parental duty drew me into her story.

While I wrote this story, there were times when I struggled to make sense of Dorothea’s choices to foster her children out to strangers, especially after she married Paul Taylor, but I had to remember that in the early 1900s commonly accepted ideas about child-rearing and child development differed from today.

People tended to emphasize the resilience of children and overlook their emotional needs. In some ways Dorothea reminded me of another woman from the same era who is celebrated for her humanitarian work: Eleanor Roosevelt.

Like Lange, Roosevelt had a fraught relationship with her children stemming largely from her active political career outside the home. The fact is that women who chose to pursue careers in the early 1900s lacked role models, mentors, affordable childcare options, and other supports that are now widely accepted to be critical to balancing motherhood with work outside the home.

. . . . . . . . . .

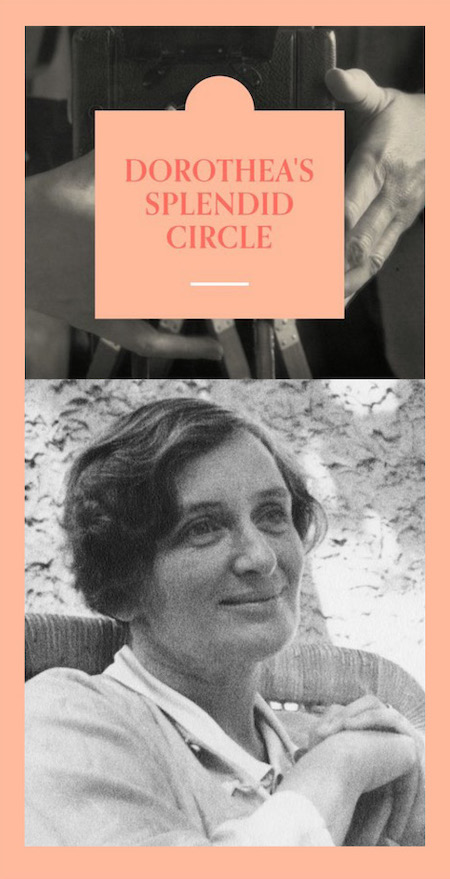

Dorothea Lange in the 1930s

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Given that Lange carried such psychic scars surrounding her own father’s abandonment, how did she justify her choices?

A: To be clear, there were some major differences between Dorothea’s father’s departure and her decision to entrust her boys to someone else’s care. She didn’t fully understand the causes for her father’s departure until years later when her mother provided more context.

He had fled his wife and children in 1907 because he was in trouble with the law as a result of some unsavory business practices. Dorothea’s mother hid it from her children, but she continued to meet with him in secret until they finalized their divorce on the grounds of abandonment in 1919.

Dorothea believed she was keeping her boys safe from a life of poverty that was unfolding around her on San Francisco’s streets and beyond. The 1930s represent an era of hard times that almost defies comprehension to us today. People were desperate to feed their families. Orphanages were packed with children whose mothers and fathers couldn’t support them.

Families disintegrated. It was a period of vulnerability and danger for many children. So, while Dan and John never forgave Dorothea for leaving them with strangers, she felt she was doing the best she could to keep them cared for and safe.

. . . . . . . . .

Learning to See is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: Why didn’t Maynard or Paul do more to help with the care of their children?

A: The expectations of the time were that women tended to children. It was that simple. Regardless of social class, it never appears to have entered into people’s consideration that men could have played a hands-on role with raising their sons and daughters.

And this trickled down to the children of this generation. Interviews with Dan Dixon when he was an adult reflect that his hurt feelings were aimed mostly at his mother. He never seemed to hold Maynard accountable in the same way that he blamed his mother for leaving him.

Q: What happened to Dorothea’s two closest friends?

A: Fronsie’s life is mostly fictionalized in this novel. After she helped to settle Dorothea in the photography studio on Sutter Street, she mostly disappears from Lange’s biographies with the exception of reappearing as a guest at Dorothea’s wedding to Maynard.

Based on a note by Paul Taylor in the transcript of Dorothea’s oral history with Suzanne Riess, it seems Fronsie ended up living in Los Angeles during the 1960s.

Imogen led a brilliant career as a photographer and lived until 1976, when she died at ninety-three years of age. She produced many books and mentored other photographers, and her work has been exhibited around the world.

. . . . . . . . .

Japanese children pledging allegiance at an internment camp, 1942

. . . . . . . . . .

Q: What happened to Dorothea Lange’s impounded photos of the Japanese American internment?

A: The army impounded the images until after the war and then they were quietly placed in the National Archives. In 1972, Richard Conrat, one of Lange’s assistants, published some of them when he produced Executive Order 9066 for the UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

It wasn’t until 2006 when Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro published their book Impounded that the photos received widespread attention.

In 2017, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum produced an exhibit entitled Images of Internment: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary of FDR’s infamous Executive Order 9066. I visited the show and viewed photographs by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and others.

Seventy-five years later these photos are still relevant and serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of maintaining civil liberties in our democracy.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

10 Fascinating Facts About Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange’s Splendid Circle

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply