Margaret C. Anderson, Founder of The Little Review

By Mame Cotter | On March 22, 2021 | Updated November 14, 2024 | Comments (0)

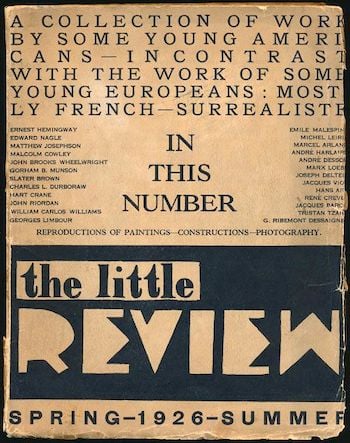

Margaret C. Anderson (November 24, 1886 – October 18, 1973) was a daring, headstrong writer, editor, and founder of the modernist literary magazine, The Little Review. This modernist journal, published from 1914 to 1929, was dedicated to the best writing and art of the early twentieth century.

Margaret was later known as one of “The Women of the Rope,” a group of writers and artists who studied with the famous Russian mystic Gurdjieff, part of a group seeking transformation and possible enlightenment.

Early life and escape to Chicago

Margaret was born in Indianapolis, Indiana to Arthur Anderson and Jessie Shortridge. The oldest of three girls in an upper-middle-class family, she grew up in a bourgeois household from which she was eager to escape.

She studied at Western College for Women in Oxford Ohio, and afterward convinced her family to allow her to go to Chicago with her sister. Chicago, a bustling city, was so different from Indianapolis, and Margaret loved it. She spent her allowance on coffee, chocolate, and fine clothes.

She bought flowers, books, and beautiful furniture; she attended concerts and performances with the best seats in the house. There were performances of Mary Garden, Isadora Duncan, Arturo Toscanini, and others that opened Margaret’s consciousness to the highest aspirations in art.

Clara Laughlin, a well-known writer and editor, gave Margaret her first writing job. She started meeting writers, artists, anarchists, and bohemians who lived for art and ideas. Her dream came crashing down when her parents demanded that she move her back to Indiana because she was spending all their money. Margaret argued, and her parents finally consented to let her move back to Chicago if she could support herself.

Margaret found work at The Dial magazine, but eventually grew restless and depressed. She knew she needed inspiration. That’s when the idea of a journal dedicated to all the arts came to her. Hers would be a life of service to the highest literature and beauty.

The Little Review was launched in 1914, headquartered in the beautiful Chicago Fine Arts building with many obstacles — not the least of which was finding funding and help in getting it published. After publishing writings in praise of Emma Goldman, the controversial anarchist and feminist, Margaret lost backers and funding.

Margaret never compromised and became resourceful. She convinced her sister to live with her on the shores of Lake Michigan in tents with wooden floors. Writers and artists would pin their works on the tent flaps if they weren’t home. Margaret and her sister swam in the mornings, then drink coffee and have breakfast on the beach. They camped on the shores until November when the cold rains came.

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret C. Anderson, 1930 (photo by Man Ray)

Watch a documentary on Margaret C. Anderson by Mame Cotter

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Heap enters

Jane Heap, a talented cross-dressing artist, joined the staff of The Little Review. She had short hair, dressed like Oscar Wilde, and had the wit to match. Margaret was enthralled when she met her; it felt like destiny, and they became lovers. Jane helped edit the journal; she and Margaret were different, yet they complemented each other.

Margaret had found the one person that understood her ideas. She felt Jane had an incredible mind and utilized it for The Little Review. They discussed and argued ideas, chiefly about art.

Margaret found a wick for her flame and Jane sent her ablaze with new energy. The two women had high standards for what they would publish in The Little Review. For one issue, they weren’t happy with the submissions, so they published 64 pages of blank white paper.

Many prominent writers such as Carl Sandburg, T.S Eliot, Ezra Pound contributed their writings to The Little Review for no payment. Some of the notable women who contributed to The Little Review include Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Mina Loy, and Dorothy Richardson, among many others.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Heap (photo by Berenice Abbot)

. . . . . . . . . .

European Writers and James Joyce

In 1917, the expatriate poet Ezra Pound joined The Little Review. He was able to get contributions from writers such as Aldous Huxley, William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, among others.

Margaret and Jane loved Joyce’s Ulysses and published segments of the novel in the magazine from 1918 to 1920. America wasn’t ready for Joyce, which led to a charged of obscenity.

Margaret and Jane didn’t worry about censors and felt Ulysses should be published for its innovative stream of consciousness technique. Margaret recognized the genius in Ulysses and tried to battle what she felt was the public’s ignorance. She grew discouraged with people who had no taste for beauty.

Women of the Rope

After editing and publishing The Little Review for eleven years, Margaret eventually left, exhausted from the fight to publish great literature. Jane Heap became the sole editor and writer for many years.

Margaret moved to France with the singer Georgette Le Blanc. They struck up a tremendous friendship and became lovers. Georgette was the former mistress of the writer Maurice Maeterlinck, author of The Blue Bird.

Margaret, Georgette, and later Jane became part of a group known as The Women of the Rope. These were woman writers and artists searching for enlightenment by studying the teachings of the great mystic G. I. Gurdjieff in Paris and Fontainebleau France. Other members included Solita Solano, Kathryn Hulme, Alice Roher, and Elizabeth Gordon.

Gurdjieff’s teachings seemed to appeal to women artists. He could be very strict but had a sly sense of humor. Solita Salano had written a detailed, fascinating book about their experience with the famous mystic called Gurdjieff and the Woman of the Rope: Notes of meetings in Paris and New York.

“You are going on a journey under my guidance, an inner-world journey like a high mountain climb where you must be roped together for safety, where each must think of the others on the rope, all for one and one for all.” (— Gurdjieff And The Women Of The Rope)

The short story writer Katherine Mansfield also studied with Gurdjieff but was not part of the group. She felt that Gurdjieff”s teaching gave her hope during her illness. His teaching impacted all of their lives and taught them a new way of seeing that would help them with difficulties. Margaret wrote a book about him called The Unknowable Gurdjieff.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Later years and World War II

Margaret and Georgette lived in a lighthouse in France. She wrote about this time almost like a fairy tale — days blend with the evening, suffused with light, flowers, wonderful meals, coffee, and wine. Margaret found Georgette’s essence to be sweet, creative, and kind. She considered Georgette a visionary artist/mystic and was devastated when she was diagnosed with cancer.

The two women felt compelled to leave Paris when World War II broke out; in addition, Georgette needed help. They moved from town to town until they ended up in Le Chalet Rose near Cannes. Ernest Hemingway gave them some money to live on since they were broke. Georgette died in 1941.

Margaret was heartbroken and secured a passport to go back to the United States. She met Dorothy Caruso, the widow of the famous tenor Enrico Caruso. They became companions and traveled together.

Despite the challenges, Margaret had lived a full and exciting life on her own terms. She broke barriers in literature and art, and wasn’t afraid to be forthright in her preference for women. She died in Le Cannet, France in 1973.

Quotes by Margaret C. Anderson

“My greatest enemy is reality and I have fought it successfully for thirty years.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have to publish. Let us print it if it’s the last effort of our lives!” (on publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses)

. . . . . . . . . .

“I believe in the unsubmissive, the unfaltering, the unassailable, the irresistible, the unbelievable — in other words, in an art of life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“As I look at the human story I see two stories. They run parallel and never meet. One is of people who live, as they can or must, the events that arrive; the other is of people who live, as they intend, the events they create.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In real love, you want the other person’s good. In romantic love, you want the other person.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by Margaret C. Anderson

- My Thirty Years War (1930)

- The Fiery Fountains (1951)

- The Strange Necessity (1962)

- The Unknowable Gurdjieff (1962)

Contributed by Mame Cotter, who blogs at The Illumination of Art: “My name is Mary Cotter but just call me Mame. I am starting a blog again to find others who share my interests. I am into the arts such as painting, film, theatre and literature. I love children’s books and many of their illustrations.I love walking , daydreaming and thinking about our existence. My favorite filmmakers are Tarkovsky, Bergman, and Dreyer. There are many incredible books, art and films that explore reality and higher dimensions. I am a secret bohemian artist that lives for art, spirit and nature.” See Mame’s piece on British poet, scholar, and mystic Kathleen Raine.

Leave a Reply