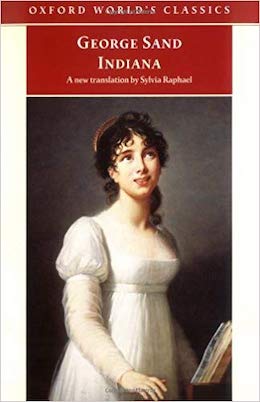

Indiana by George Sand: The Author Answers Her Critics

By Nava Atlas | On September 25, 2017 | Updated December 11, 2022 | Comments (0)

George Sand’s first novel, Indiana (1832), argued for the freedom of young women to follow their hearts, make their own terrible mistakes, and learn from them in order to grow and be true to themselves. Only then could they become equal partners to their husbands.

Indiana is a young woman married to a much older man. She falls in love with a rake who has seduced her own maid. Indiana’s passion is nonetheless awakened by her perfidious lover.

The restrictive French marriage laws of the time and double standards of the time created a perilous path for Indiana’s passage to womanhood.

Critics of that time considered the novel shocking, scandalous stuff coming from the pen of a woman (George Sand’s masculine nom de plume apparently didn’t mask her identity).

But Sand always gave back as good as she got. She wasn’t afraid to answer her critics, any more than she was afraid to wear men’s clothes and smoke cigars in public and travel alone — things a women just didn’t do in those days. I

ndiana had a long life in print; here’s a portion of her introduction to the 1852 edition (translated from the original French):

George Sand answers her critics

“I wrote Indiana during the autumn of 1831. It was my first novel; I wrote it with no fixed plan, having no theory of art or philosophy on my mind. I was at the age when one writes with one’s instincts, and when reflection serves only to confirm our natural tendencies.

Some people chose to see in the book a deliberate argument against marriage. I was not so ambitious, and I was surprised to the last degree all the fine things that the critics found to say concerning most subversive purposes.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

To George Sand: A Desire, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . . .

Criticism is far too acute; that is what will cause its death. It never passes judgment ingenuously on what has been done ingenuously. It looks for noon at four o’clock, as the old women say, and must cause much suffering to artists who care more for its decrees they are to do.

… at the time that I wrote Indiana the cry of Saint Simonism was raised on every pretext … even now certain riders are forbidden to open their mouths, under pain of seeing police agents of certain newspapers pounce upon their work and hale them before the police of the constituted powers.

If a writer puts noble sentiments in the mouth of a mechanic, it is an attack on the bourgeoisie; it’s a girl who has gone astray is rehabilitated after expiating her sin, it is an attack on the virtuous women; if an imposter assumes titles of nobility, it is an attack on the patrician cast; if a bully plays the swashbuckling soldier, it is an insult to the Army; if the woman is maltreated by her husband, it is an argument in favor of promiscuous love.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

And so was everything. Kindly brethren, developed and generous critics! What a pity that no one thinks of creating a petty court of literary inquisition in which you should be the torturers!

Would you be satisfied to tear the books to pieces and burn them at a slow fire, and could you not, by your urgent representations, obtain permission to give a little taste of the rack to those writers who presume to have other gods than yours?

Thank God, I have forgotten the names of those tried to discourage me at my first appearance, cool, being unable to say that my first attempt had fallen completely flat, tried to distort it into an incendiary proclamation against the repose of society.

I did not expect so much honor, and I consider that I owe to those critics the thanks which the hare proffered the frogs, imagining from their alarm that he was entitled to deemed himself very thunderbolt of war.”

— George Sand, Nohant, 1852

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: The Mellowing of George Sand

Leave a Reply