Ban if You Can: Banning & Censorship in Contemporary India

By Melanie P. Kumar | On July 25, 2024 | Comments (0)

India’s celebrated diversity and, by and large, a sense of peaceful co-existence has taken a severe hit since the past decade. This has been linked with the rise of right-wing Hindutva in politics, which has bred a sense of injured pride in the Hindu majority accompanied by a phobia created about the threat from minorities, most of all Islam.

The myths being perpetrated include the uncontrolled rise in the Muslim population, as also the physical threats that could result from this change in demographics.

There is no data to substantiate these claims but with the power of social media and its ability to make a piece of fake news viral, nobody seems to care anymore to do a fact check and most people are quite content to believe all the lies that land on their telephones, day in and day out.

At such a juncture, all forms of media including books, have the power to influence people and change minds. Hence, governments and powerful religious groups are very sensitive about certain topics, which they feel the public should be denied access to. With this started the history of bans in India, though it is not as if other more progressive countries have not done their share of banning.

Book banning in India

Aubrey Menen and Salman Rushdie

One of the earliest books to be banned in India was Rama Retold. Written in 1954 by the British writer Aubrey Menen as a spoof with a dose of humor, it clearly did not appeal to the funny bone of Indians and the book was prevented from being imported into India.

The author, labeled as a satirist, novelist and theatre critic, was probably much more, as he took pot shots at all the characters in the Ramayana, including the one who is said to have authored the Ramayana, Valmiki.

In today’s India, this retelling might have brought him death threats and though he chose to make India his home in later life, he fortunately didn’t live to see this phase of India’s authoritarian grip on the written and spoken word.

Sometimes, as it happened with Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, it is the fear of communal conflagrations that can result in a ban. Even though the book made it to the Booker shortlist, the government headed by the Congress party under Rajiv Gandhi, decided to play safe and enforce a ban on the book.

In 1989, there was a fatwa put on Rushdie by Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran and the author had to go into hiding for long years. It is tragic how Rushdie nearly paid with his life in August 2022, despite years having gone by, since the fatwa was lifted.

One is not sure whether the misguided assailant had even read the book. Rushdie’s cup of woes did not end with the Satanic Verses in India.

His Moor’s Last Sigh, also came in for criticism and protests in the state of Maharashtra, as one of the characters seemed to bear a resemblance to Balasaheb Thackeray, the founder of a political party called the Shiva Sena. That Thackeray started his career as a journalist, makes this all the more ironic.

Dan Brown

When it came to Dan Brown’sThe Da Vinci Code, it was India’s Christian population that rose up in protest claiming that the book had made profane statements on Christ.

Despite selling millions of copies worldwide, after the movie version was released in 2006, the book was prevented from being “sold, distributed and read.” The movie also came in for a ban in several states of India, where the Christian population were located in large numbers.

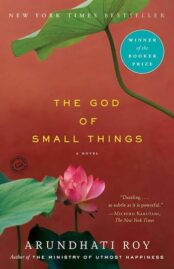

Arundhati Roy

In a country steeped in patriarchy, many women authors have had to face criticism of their books, if not outright bans. Arundhati Roy, who won the Booker Prize for her God of Small Things, had to fight a case, as a lawyer in Kerala was offended by her book with its reference to an upper caste Kerala woman cohabiting with a man from a lower caste.

But truth is stranger than fiction. Even today the papers are full of stories of families attacking couples belonging to different castes, with some of them ending in the tragic death of one or both.

Indian patriarchy strangely extends across the different religions that have incubated here. At the heart of this sense of ownership of a woman is likely linked to an ancient lawmaker, Manu, who in his Manusmriti, has clearly spoken of a woman as a piece of property and drawn the most demeaning parallels about her position in society.

That the present Union government is trying to bring in the Manusmriti as a part of its newly amended criminal laws, has led to a lot of protests, including from those of the legal fraternity. If Manu’s code is revived by this government, it will certainly be back to the dark ages for the women of India, especially those who live in the villages and small towns, with less access to education and an already internalized acceptance of patriarchy.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Kamala Das

Another woman author who had to face a great deal of censure was the Malayalam author, Kamala Das, who wrote fearlessly about a woman’s body and its needs.

Her writings shook society and Das had to face a huge backlash from an orthodox society. But she was unfazed and continued writing till her last breath. Even today, her writings make up a big part of feminist Indian writing.

Poet, author, social scientist and feminist Kamla Bhasin put it succinctly when she observed, “My honour is not in my vagina.” The tragedy of patriarchy is in its belief that this is where a woman’s honor vests.

In recent times, the politics surrounding food have also led to the banning of movies, including those available for live streaming. While propaganda films have managed to garner awards in the last ten years, the right-wing ecosystem seems to exercise strict control about what films are suitable for viewing by the Indian public.

A contemporary film banned

It’s enough for just one person to see a movie, feel outraged by it and have it banned by posting about it on social media. One such film, which was removed from Netflix was Annapoorani: The Goddess of Food. The furor over “hurting Hindu religious sentiment,” resulted in its removal at its “licensor’s request.”

The gist of the story revolves around actor, Nayanthara, aspiring to become a cook by learning to eat and prepare non-vegetarian dishes, which are taboo in a Brahmin home. It’s another story that many Indians from the upper castes have broken this taboo, but of course this is again a question of patriarchy rearing its head in that a woman does not have a right over her food choices either.

The role of India’s government in banning and censorship

In earlier times, governments banned books or movies in anticipation of trouble, or because they felt jittery over certain allusions in books and the popular media.

Today the government has managed a huge stranglehold on the dissemination of information. The mainstream media has largely become a propaganda machine for the government and has earned for itself the title of Godi or Lap Media.

Many activists find themselves in jail over trumped up charges of spreading fake news. The independent media is always up for censure with several journalists feeling threatened about how they cover news. Even stand-up comics have not been spared, with many of their shows being called off because someone protested during the event, or prior to the staging.

The author Aubrey Menen, mentioned earlier, put it best in his closing lines of Rama Retold, which he reserved for his favorite character, Valmiki:

“There are three things, which are real: God, human folly and laughter. Since the first two pass our comprehension, we must do what we can with the third.”

It is sad that Indians seem to have missed out on the joys of laughing at their own foibles because at the end of the day, it is just the fact of having a very thin skin, especially our politicians.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

Leave a Reply