10 Fascinating Facts About Christina Rossetti, Victorian Poet

By Diane Denton | On September 16, 2023 | Updated September 21, 2023 | Comments (0)

Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830 – 1894) is among the most important female poets of the 19th century. Presented here are fascinating facts about Christina Rossetti, the Victorian English poet whose work continues to resonate and inspire.

Her popular works, including “Goblin Market,” “Remember,” “In an Artist’s Studio,” “Who Has Seen the Wind,” and “In the Bleak Midwinter,” are a small part of her prolific output.

The American author Elbert Hubbard wrote in Christina Rossetti , “Christina had the faculty of seizing beautiful moments, exalted feelings, sublime emotions … In all her lines there is a half-sobbing tone.”

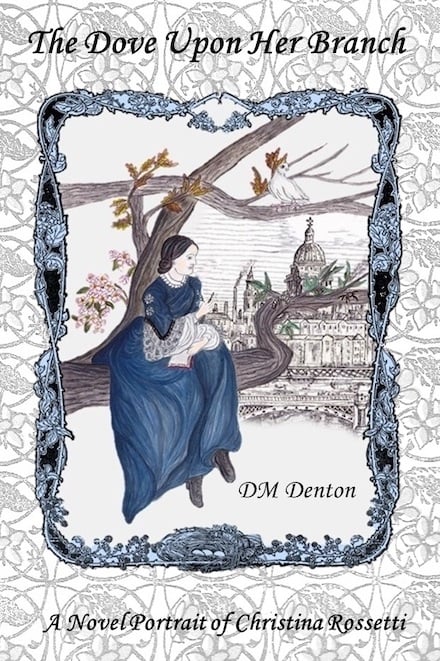

DM Denton’s new novel, The Dove Upon Her Branch: A Novel Portrait of Christina Rossetti (2023) takes the reader deep into the heart of the fascinating and remarkably gifted Rossetti family, unveiling Christina’s life from childhood to middle age, through her encounters with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, her development as a poet, family changes and tragedies, and struggles with her health and salvation.

. . . . . . . . .

The Dove Upon Her Branch by DM Denton

is available on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Christina’s lineage was more Italian than English

Christina has been portrayed as the quintessential English woman and in many ways she was. Her English blood came by way of her maternal Middlesex grandmother Anna Pierce, who married Tuscan scholar Gaetano Polidori, an immigrant who settled in London.

We Englishwomen, trim, correct,

All minted in the self-same mould,

Warm-hearted but of semblance cold,

All-courteous out of self-respect.

(from “Enrica” by Christina Rossetti)

Christina’s father, Gabriele Rossetti, a Neapolitan nobleman and political exile, befriended Gaetano and courted his eldest daughter, Frances. Her “passion for intellect” persuaded her to marry Gabriele rather than a much better-situated but less interesting Scottish colonel.

Many expatriate Italians—the humblest and highest—called at Christina’s childhood homes. She visited Italy only once, but through her written reflections it’s obvious she felt it was her essence: “Take my heart, its truest part, Dear land, take my tears.” (from“En Route” Christina Rossetti)

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Christina Rossetti

. . . . . . . . .

Christina was a child with fiery emotions

“One one occasion, for being rebuked by my dear mother for some fault, I … ripped open my arm to vent my wrath,” Christina reportedly told her niece. She was a high-spirited, willful, and often fractious little girl, happy to be indulged.

Her temperament was more aligned with her oldest brother Gabriel than their other siblings. Their father referred to Christina and Gabriel (renowned later as the artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti) as “the storms” in the family, Maria and William “the calms.”

Adolescence changed her. Family, friends, and even several doctors couldn’t decide why. Was it because she spent too much time alone with her aging, ailing father, the delay of her monthlies, restricting piety, the strain of her intellect and creativity, or the Victorian go-to for female melancholia and poor health, hysteria?

The little girl of tears and tantrums but also uninhibited playfulness and passion was, if not entirely gone, properly subdued, eventually under the appearance of a disciplined, dutiful, devotional woman.

A city dweller, Christina was inspired by nature

In her poem “Summer,” Christina wrote: “… one day in the country is worth a month in town.” As an observer noted, Christina enjoyed the pastoral life “with a fearless love … country children could never emulate.”

Her Grandparents Polidori owned a cottage in the Buckinghamshire village of Holmer Green. “If one thing schooled me in the direction of poetry,” she reflected, “it was perhaps the delightful liberty to prowl all alone about my grandfather’s cottage grounds.” (from Christina Rossetti’s Letters)

Even in London, there were opportunities to observe and enjoy nature, including Regents Park, its Zoological Gardens, and Primrose Hill.

Eventually, her grandparents moved to an Italianate villa on the northern corner of Regents Park, “one side in the town and the other in the country,” satisfying both her grandfather’s and her needs as “creatures of both.” (from Christina Rossetti’s Letters)

. . . . . . . . .

Illustration from

The Dove Upon Her Branch by DM Denton

. . . . . . . . .

Christina’s promise as a poet was encouraged by her family

It must have been stimulated by a game bouts-rimés she played with her siblings, a race between two of them to compose a sonnet using a set of end rhymes a third came up with. She pleased her mother with her earliest verses.

Maria kept a notebook of her little sister’s poems. Christina first saw her poetry in print when she was seventeen, owing to the adoring insistence and personal printing press of Nonno Polidori. Her brothers often proofread and critiqued her writing, negotiated with publishers, and Gabriel contributed illustrations.

“I’m luckier than some, with a family that encouraged me to do the one thing I’m fairly good at. And long before I could claim any income from it.” (from The Dove Upon Her Branch, A Novel Portrait of Christina Rossetti by DM Denton)

Christina almost avoided being a governess

When her father, who was seventeen years older than her mother, became too ill to support his family, his wife, youngest son, and oldest daughter had to find employment. Gabriel was only expected to pursue his art.

For Maria, like so many unmarried lower- or middle-class females in the 19th century, being a governess was the obvious option. Christina was left at home to take care of her nearly blind, demanding, depressed father.

Her brother William saw the blessing in her situation. “So here you are. Not sent off to be a governess but left behind to be a poet; surely a better way to make a few bob.” (from The Dove Upon Her Branch, A Novel Portrait of Christina Rossetti by DM Denton)

As for Maria’s assumption that her sister “wouldn’t last a week as a governess,” twenty-five-year-old Christina made it through a couple of months at Haigh Hall in Lancashire as a temporary nanny for one of her Aunt Charlotte’s connections. Christina’s own words speak to how she felt about the experience she called my exile, happy to confirm her health did “unfit her for miscellaneous governessing en permanence.” (from Christina Rossetti’s Letters)

For a short time, she helped her mother run two small day schools in their residences, first in London on Arlington St. and then in Frome, a country town in Somerset. Christina disliked teaching, too, so as both schools failed, she was once again relieved of an occupation she was unfit for.

. . . . . . . . .

Illustration from

The Dove Upon Her Branch by DM Denton

. . . . . . . . .

Christina posed as a model for several artists

The fledgling, free-and-easy Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (P.R.B.) often met upstairs in her Charlotte Street home. At eighteen, pretty and naïve, she went to the grungy studio across from a workhouse Gabriel shared with William Holman Hunt.

Opportunely realizing Christina’s innocent look fit the bill and wouldn’t cost him anything, Gabriel brought her in for the role of the Virgin Mary as a girl, along with their mother for Saint Anne and chaperoning her vulnerable daughter from any unsuitable influence.

Gabriel did set Christina up to be courted by one of the Brotherhood’s members, albeit one who was “priestlike” and narcoleptic. Although never a bona fide member of the P.R.B., Christina contributed—first anonymously, then under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne—to its publication, The Germ.

In addition to another Virgin Mary painting, she posed for the head of Jesus in Hunt’s The Light of the World, eventually her face irrelevant, surrounded by the fire and flow of a real model’s—Lizzie Siddal’s—hair.

In her mid-thirties, Christina sat for the artist William Bell Scott who was designing murals for Penkill Castle, the Scottish home of his mistress Alice Boyd. Christina’s visit there might have been judged unwise for Mr. Scott’s wife was also one of the guests of Miss Boyd.

Somehow Christina safely navigated the scandalous situation and, even as she intimately modeled for him, the attention of a man she possibly was attracted to.

. . . . . . . . .

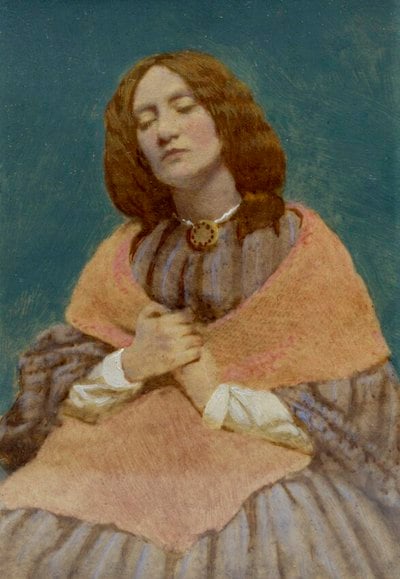

Elizabeth Eleanor “Lizzie” Siddal, whom Dante Gabriel Rossetti

used as a model in many well-known paintings

. . . . . . . . .

Christina had little interaction with her brother’s wife

Lizzie (Elizabeth) Siddal, the model, painter, and poet, was a significant part of Christina’s brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s life. Lizzie was his muse, student, and fiancé; later his wife and haunting vision.

Although Lizzie was often not far away in London, frequenting and eventually living at Gabriel’s Chatham Place, Blackfriars residence, it was only many years after she and Gabriel became a couple that Christina met her.

And downcast were her dovelike eyes, and downcast was her tender cheek,

Her pulses fluttered like a dove

To hear him speak.

(from “Listening” by Christina Rossetti)

When Lizzie became pregnant Christina hoped that once she was a doting aunt, she and her sister-in-law might become closer. Then a baby girl was stillborn, and Lizzie’s overdose of grief and laudanum determined what would never happen.

Christina forayed into several social causes

Christina was in her mid-twenties when she applied to join Florence Nightingale’s mission in the Crimea, following the example of her Aunt Eliza Polidori. Eliza was accepted, but Christina wasn’t. A few years later, she turned to a cause utilizing her belief in forgiveness and redemption over punishment and hopelessness.

Ironically, as Sister Christina, donning a black dress with hanging sleeves, a muslin cap, string of black beads, and silver cross, she emerged from her cloistered family life to volunteer at the St. Mary Magdalene Penitentiary on London’s Highgate Hill, a charitable institution that focused on “the reception and reformation of penitent fallen women with a view to their ultimate establishment in some respectable calling.” (Ad for the St. Mary Magdalene Penitentiary)

Christina organized petitions for the rights of minors and anti-vivisection and in support of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, which included raising the age of consent for girls to sixteen.

She didn’t support women’s suffrage, leaving herself out when she made an exception for married women: “For who so apt as Mothers — all previous arguments allowed for the moment — to protect the interests of themselves and of their offspring?” (from Christina Rossetti’s Letters)

Christina never married, though not for lack of opportunity

She received at least three marriage proposals, two by the same man. A poem, “No, Thank You, John,” hints there was a fourth.

When she was seventeen, Christina caught the eye of the painter James Collinson; Christina turned him down because he was leaning towards Catholicism. He proposed a second time with the assurance he would remain an Anglican, their disengaged engagement dragging on for a few years until Collinson decided to go to a Catholic Seminary College.

The linguist Charles Bagot Cayley had been a student of her father’s, a shy, unworldly, disheveled, dry-witted intellectual who eventually proposed to Christina, but his agnosticism forced her to refuse him. They remained platonically affectionate.

Between Collinson and Cayley, the painter John Brett may have asked Christina to marry him.

The 1963 biography, Christina Rossetti by Lona Mosk Packer, sets out the theory that some of Christina’s poems show she had a strong affection for a secret someone. Ms. Packer believed he was the Scottish painter and poet William Bell Scott, a good friend of the Rossettis but a married man with a mistress. Whether he was the reason Christina rejected the others remains a controversial possibility.

Christina suffered from Graves’ Disease

In her early forties, having been prone to various ailments, Christina’s health suddenly and severely deteriorated.

She was diagnosed with Graves’ Disease, at the time a little understood autoimmune thyroid condition. Her brother William described her as a “total wreck;” Gabriel claimed she looked ten years older: her eyes bulging, hair falling out, skin discolored, and swelling on her neck.

For a while, she was barely able to walk. And although she experienced remissions, alterations to her appearance were mostly permanent, causing her to become even more reclusive.

It was another disease that snatched the chance of the Poet Laureateship and living a long life from her. After Tennyson, Poet Laureate since 1850, died in 1892, Christina was considered a contender to succeed him.

At the time she seemed well recovered from a mastectomy, but with a delay of a few years before Queen Victoria made an appointment, time wasn’t on Christina’s side. She died in December 1894 from a recurrence of breast cancer.

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

(from “Remember” by Christina Rossetti)

. . . . . . . . .

More about Christina Rossetti

- Goblin Market (full text)

- 12 Poems by Christina Rossetti, Victorian Poet

- The Poetry of Christina Rossetti: A 19th-Century Analysis

Contributed by DM (Diane) Denton, a native of Western New York, a writer and artist inspired by music, nature, and the contradictions of the human and creative spirit.

Her historical fiction A House Near Luccoli, which is set in 17th century Genoa and imagines an intimacy with the charismatic composer Alessandro Stradella, and its sequel To A Strange Somewhere Fled, which takes place in late Restoration England, as well as Without the Veil Between, Anne Bronte: a Fine and Subtle Spirit, were published by All Things That Matter Press, as were her Kindle short stories, The Snow White Gift and The Library Next Door.

Diane has done the artwork for all her novels’ book covers, and published an illustrated poetry flower journal, A Friendship with Flowers. Visit her on the web at at DM Denton Author & Artist and BardessMDenton.

Leave a Reply