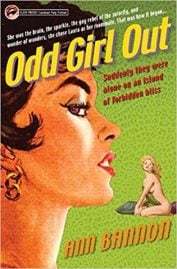

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy), 1957

By Francis Booth | On March 23, 2021 | Updated April 19, 2025 | Comments (0)

Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (the pseudonym of Ann Weldy), was one of several hugely influential lesbian pulp novels of the 1950s. This appreciation and analysis is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In the introduction to her anthology Lesbian Pulp Fiction, the author Katherine V. Forrest remembers how a book she found in a bookshop in Detroit in 1957 changed not only her writing but her life:

“Overwhelming need led me to walk a gauntlet of fear up to the cash register. Fear so intense that I remembered nothing more, only that I stumbled out of the store in possession of what I knew I must have, a book as necessary to me as air. The book was Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon. I found it when I was eighteen years old. It opened the door to my soul and told me who I was. It led me to other books that told me who some of us were, and how some of us lived.

Finding this book back then, and what it meant to me, is my touchstone to our literature, to its value and meaning. Yet no matter how many times I try to write or talk about that day in Detroit, I cannot convey the power of what it was like. You had to be there. I write my books out of the profound wish that no one will ever have to be there again.”

Bannon was really Anne Weldy; she had the same editor, Dick Carroll, and the same publisher, Gold Medal Books, as Vin Packer/Marijane Meaker, author of Spring Fire. As Bannon had changed Forrest’s life, so Meaker had changed Bannon/Weldy’s.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Meeting Marijane Meaker and Dick Carroll

Weldy had been in a sorority at college like the characters in Spring Fire and thought she could write a similar kind of novel. She wrote Meaker “a kind of a fan letter.” Even though Meaker had been getting hundreds of fan letters she responded, inviting Bannon to meet her and Carroll, who looked at her novel and saw both problems and promise in it.

“In the view of Dick Carroll, the twinkly old Irishman who was running that show, the manuscript was twice as long as they wanted. He also felt that I hadn’t recognized my story. I had told a kind of straightforward coming of age type novel, and rather cautiously and timidly put a small romance between two young women in the corners of the background. He said cut the length by half and tell the story of the two young women, Beth and Laura, and then maybe we’ll have something.”

Unlike Meaker, Weldy was allowed to write the ending she wanted. In a later interview she said that Meaker “was constrained very heavily in having to end her book on a very negative note. Writing five years later, I found things had loosened up. I was able to, in a sense, have a happy ending.”

Weldy told the same interviewer how difficult life was for homosexuals and lesbians in the early 1950s, in the middle of the Cold War, the McCarthyite anti-communist witch hunts and the paranoia that surrounded them.

“It was a very repressed and frightening time. After World War Two ended, the country had made a frightening turn and embraced the most conservative and traditional roles. All the girls were supposed to be home having babies and making soup and casseroles. Everyone was supposed to be as conventional as is possible to imagine.

People whose nature led them to a same-sex attraction were forced to put up a conventional façade. The danger was very severe, and gay attraction was frankly illegal in a lot of places. You could be jailed, you could certainly be publicly humiliated and everything could be thrown into jeopardy in terms of your job and your family.

You were treated almost as if you had a disease, and if you were known to be gay then your friends had to abandon you because they might catch it too.”

Marijane Meaker put it in a very similar way in a later introduction to a reprint of We Walk Alone.

“In the 50s, we felt no entitlement, and most of us were wary of any organizations. The 50s was famous for its witch-hunts and congressional investigations. In the eyes of the law we were illegal, and religions viewed us as anathema. I wanted to write about what it was like to live in one of the most sophisticated cities in the world, and find yourself unacceptable because of your sexual orientation.”

First of The Beebo Brinker Chronicles

Odd Girl Out was the first of what became The Beebo Brinker Chronicles: five linked novels from 1957 to 1962, of which the second, I Am a Woman, 1959 and third, Women in the Shadows 1959, follow the same character, Laura into maturity. But Weldy was a very unlikely pioneer of lesbian fiction.

“I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of 22 to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience.

I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world… To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century.”

Originally introduced to it by Marijane Meaker, Weldy spent time in New York’s Greenwich Village. “It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration.”

Odd Girl Out: A brief synopsis

Weldy’s debt to Meaker extends to the plot of Odd Girl Out, which, like Spring Fire, concerns an inexperienced girl, Laura, going to college and falling in love with an older member of her sorority, Beth, but being unsure what her feelings mean and what to do about them.

“There was a vague, strange feeling in the younger girl that to get too close to Beth was to worship her, and to worship was to get hurt.” Beth is a larger-than-life character; Laura “had never met or read or dreamed a Beth before.” One of Beth’s eccentricities is that she never wears underwear. Laura’s “whole upbringing revolted at this… Nobody was a more rigid conformist, farther from a character, than Laura Landon.”

Sharing a room together, Laura is very shy about getting undressed in front of another person, feeling that “Beth’s bright eyes were doting on every button.” Beth makes up the bed for her.

“She helped Laura under the covers and tucked her in, and it was so lovely to let herself be cared for that Laura lay still, enjoying it like a child. When Beth was about to leave her, Laura reached for her naturally, like a little girl expecting a good-night kiss. Beth bent over and said, ‘what is it, honey?’

With a hard shock of realization, Laura stopped herself. She pulled her hands away from Beth and clutched the covers with them.

‘Nothing.’ It was a small voice.

Beth pushed Laura’s hair back and gazed at her and for a heart-stopping moment Laura thought she would lean down and kiss her forehead. But she only said, ‘Okay. Sleep tight, honey.’ And climbed down.”

Laura knows nothing of lesbianism and is simply “fuzzily aware of certain extraordinary emotions that were generally frowned upon and so she frowned upon them too, with no very good notion of what they were or how they happened, and not the remotest thought that they could happen to her.”

She had had crushes on girls in high school but “they were all short and uncertain and secret feelings and she would have been profoundly shocked to hear them called homosexual.” Laura of course considers herself normal even though she “wasn’t attracted to men. She thought simply that men were unnecessary to her. That wasn’t unusual; lots of women live without men.”

Like Mitch in Spring Fire, Laura has to fight off the unwanted attentions of a boy from college who will not take no for an answer; in this case he does not go so far as to rape her, but still, like Mitch, her first experience with a boy is very bad.

Also like Mitch, Laura’s love object Beth has a boyfriend; Laura, as she begins to understand her true nature – as she comes of age – knows she has to give Beth up to him; “you need a man, you always did.”

“‘I’m not wrong about myself, not any more. And not about you, either.’

‘Oh, Laura, my dear –’

‘We haven’t time for tears now, Beth. I’ve grown up emotionally as far as I can. But you can go farther, you can be better than that. And you must, Beth, if you can. I’ve no right to hold you back.’ Her heart shrank inside her at her own words…

‘You taught me what I am, Beth. I know now, I didn’t before. I understand what I am, finally.’”

. . . . . . . . .

Odd Girl Out on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Ann Bannon and Odd Girl Out

- Ann Bannon: Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction

- Beebo’s Significant Other

- The Lesbian Pulp Fiction Collection

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply