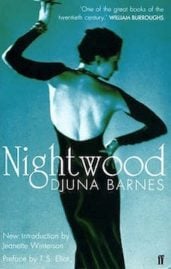

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes (1937) – a review

By Nava Atlas | On July 14, 2017 | Updated December 29, 2024 | Comments (0)

Nightwood is the best-known of the novels of Djuna Barnes, the American-born expat who spent much of her life among the lesbian circles in 1930s Paris. Published in 1936, it has long been considered her literary masterpiece, and is still regarded as one of the most influential works of modernist fiction.

This experimental novel explores the lives and loves of five eccentric and extraordinary people, and may be the first modern novel with a transgender character.

Nightwood was edited by T.S. Eliot. Barnes, then in her mid-40s, was still overwhelmed by the breakup with her lover, Thelma Wood. The novel follows the obsessive love affair of two women, which led to Barnes being called a “lesbian evangelist.” Despite the real-life parallel, Barnes despised and denied the label.

A 1936 review of Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

From the original review of Nightwood by Djuna Barnes in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 1937: This is a rare and tempting book, because it might be easily underestimated and just as easily overrated.

The introductory praise by T.S. Eliot, which is meant to attract serious readers, will perhaps lead to a few of them to contradict his opinion; and certainly Mr. Eliot’s advice is the best way to understand a rather perplexing book:

“I have read Nightwood a number of times, in manuscript, in proof, and after publication … for it took me some time to come to an appreciation of its meaning as a whole.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Djuna Barnes

. . . . . . . . . .

It benefits from rereading

Having read it twice myself, in some parts even the third time, I can support Mr. Eliot’s claim that the book becomes more impressive with each rereading.

Whether continued reading would increase one’s admiration still more, and whether Mr. Eliot’s numerous readings entitle him to a sounder judgment then someone less initiated, I am hardly able to say. But for the moment it seems to me the kind of book that would make an intense personal appeal to those, like Mr. Eliot, whose view of life it corroborates.

Without much argument, I think Miss Barnes can be called a writer of great distinction and virtuosity, an artist highly developed within her special and somewhat exotic limitations. Perhaps the first question is whether her talent, is this book displays it, opens up any further possibilities.

A modernist period piece

Her novel belongs quite obviously to a period — the neurotic postwar years, and to a particular school of writing — the followers of Ulysses. Miss Barnes is herself and American living in Paris; and her characters are those familiar and extraordinary people who hunt the cafés, stroll in strange costumes through the Luxembourg Gardens, and who band together like a religious order around the Place St. Sulpice.

It is a small and eccentric world, already vanishing or merging into new and different forms, I feel that Miss Barnes, in reconstructing it with such power and concision, has to some extent lost herself in the past.

For the book creates its own perspective, it seems tied down and oppressively circumscribed — the record of the generation which is being rapidly swallowed up and who’s peculiar experience can never be fully communicated.

That is one of the reasons for rereading Miss Barnes and one of the difficulties in critiquing her book. So much if it has the quality of an epigram, something suspiciously neat and yet obscurely truthful.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Craftsmanlike writing

Merely as a piece of writing, the book is remarkable and immensely interesting. It is a pleasure to find a writer as craftsmanlike as Miss Barnes, knowing exactly what she wants to do and how to do it. The novel reminds one of those geometric outlines which Henry James submitted to his publishers.

Chapter follows chapter with tolling precision, every word counts, and Miss Barnes shows that a fresh and simple use of language is still possible.

There are also passages, in one case an entire chapter, in which Miss Barnes sustains magnificent rhetorical effect with the mastery comparable to Joyce.

She has taken more than a style from Ulysses, not only the religious motifs, the grotesqueness, and the ribaldry, but even her best character — the windy-mouthed Dr. O’Connor, is rich and all-embracing as Mr. Bloom.

But her book is not an imitation, it’s only because it has grown out of the same conditions and expresses the same desolate and sardonic state of mind.

. . . . . . . . . .

Eccentric and Morbid Quotes by Djuna Barnes

. . . . . . . . . .

A great achievement, but not first rank

Mr. Eliot has summed it up as “the great achievement of style, the beauty of phrasing, the brilliance of wit and characterization, and a quality of horror and doom very nearly related two Elizabethan tragedy.”

Boiled down, it amounts only to a style and a kinship with Elizabethan tragedy — both rare and valuable sayings but scarcely enough to establish Miss Barnes as a writer of the first rank.

Probably most readers will not agree with Mr. Eliot that all the characters “have gone on living in my mind.” In spite of her occasional stabs of penetration, Miss Barnes’ oblique method seems to me ill-suited to the delineation of people as we know and deal with them, and I found her characters extremely hard to catch hold of.

In drawing a kind of spiritual relationship, she is often uncannily successful, and especially the doctor, while he talks, has an actors magnified reality. But on the whole I felt that Miss Barnes had used her characters mainly as outlets for her own verbal and emotional satisfaction.

Two points, both emphasized by Mr. Eliot, are essential for getting the most out of a very worthwhile book and for giving it the right amount of importance. “The book is not a psychopathics study.”

Miss Barnes’ characters are what is smugly called “abnormal” —men and women with the inverted sexual instincts. The most sensible attitude, in reading about them, is to ignore this fact, and their queer affairs at once become hardly distinguishable from the affairs of any unhappy person.

Moral uplift from “not disapproving”?

Or as Mr. Eliot says, in his most bishop-like tone, “to regard this group of people as a horrid sideshow of freaks is not only to miss the point but to confirm our wills and harden our hearts in an inveterate sin of pride.”

This sounds as if Mr. Eliot derived a certain moral uplift from not disapproving, and he has another phrase about “the human misery and bondage which is universal,” suggesting that the book helps to substantiate his faith in Christianity.

It seems unfortunate a critic as scrupulous as Mr. Eliot should intrude his religious beliefs into the most ordinary kind of literary criticism, and on that account I feel his introduction is in one respect unreliable. The merits of Miss Barnes’ work are sufficient, without mixing them up with religion.

Among other things, in fact, her book is an excellent companion piece for The Waste Land, a very fine example of surrealism, and a picture of a narrow and ill-fated segment of life but one which still has a curious and timely fascination.

Leave a Reply