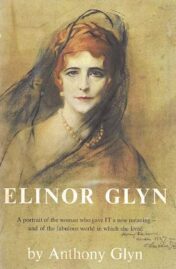

Elinor Glyn, a Biography by Anthony Glyn (1955)

By Taylor Jasmine | On November 16, 2023 | Comments (0)

Elinor Glyn (October 17, 1864 – September 23, 1943) was best known as the author of the scandalous 1907 novel Three Weeks and for coining the expression “It Girl.” The following is adapted from a review of Elinor Glyn, a biography by Anthony Glyn (her grandson).

Elinor Glyn: A Portrait of the Woman Who Gave IT a new meaning — and of the fabulous world in which she lived originally appeared in the Orlando Sentinel, July 17, 1955:

Elinor Glyn is the writer who made the word IT synonymous with sex appeal. That was Sam Goldwyn’s idea, though Mrs. Glyn had a much more involved definition.

Glyn was a legend in her own time. Born on the Isle of Jersey (UK), she died a few weeks before her seventy-ninth birthday.

Marriage, affairs, and good living

She was a young woman in the reign of Queen Victoria, a welcome guest at the house parties at the fabulous estates during the high-living Edwardian era. The object of these festivities was good living, good food, good company, exclusive society, sport, and discreet philandering.

Elinor, a slim, queenly, green-eyed red-haired beauty, had fastidiously refrained from love affairs, for she was determined to make an advantageous marriage. At the age of twenty-eight, in April 1892, at a fashionable wedding at St. George’s, Hanover Square, she married Clayton Glyn, “The most perfect grand seigneur that I have ever met.”

Clayton Glyn was a descendant of Sir Richard Carr Glyn, banker and Lord Mayor of London. he had no business interests and lived the life of a wealthy country gentleman. He was a fine sportsman, a connoisseur of food and wine, a great traveler, and absolutely irresponsible about money. He had a dry, caustic sense of humor.

Elinor’s beauty enchanted him and her pretensions and romantic silliness amused him for a time. Although they soon became indifferent to each other, they remained married until his death in 1915.

She consoled herself with other love affairs, the most famous being her eight-year romance with Lord Curzon. He evidently tired of her possessiveness and probably to avoid the dramatic scene of which he knew she was capable, let her read of his coming marriage to another woman without any advance preparation.

Elinor Glyn was an intimate of famous statesmen as well as of the nobility of Great Britain and the continent. She was a celebrated hostess and a war correspondent at the front in World War I.

A darling of the Jazz Age, she was a contradictory creature. Having inherited from her indomitable grandmother (the daughter of an Irish peer set down in the Canadian wilderness) an intense regard for the importance of aristocratic lineage.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Hollywood of the 1920s and beyond

Glyn was a dazzling figure in Hollywood of the twenties. She could yet have a wonderful time among her something less than aristocratic colleagues in the movie business — Charlie Chaplin, Clara Bow, Sam Goldwyn, Gloria Swanson, William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, Aileen Pringle, Rudolph Valentino, and others.

When she learned that her husband’s considerable fortune was gone, she could turn out bestsellers, articles, and short stories by the dozen. Even when almost destitute, her normal entourage consisted of a personal maid and chauffeur.

She rented or bought big houses in England, France, and the U.S., decorating them with her favorite color, purple. Willfully uneducated, except in the classics, she consorted with some of the brainiest men of the era.

Bestsellers that were pure tripe

Glyn’s writings were purest tripe, erotic and as fruitfully purple as her favorite color scheme. Yet Three Weeks sold five million copies and many of her other books were also bestsellers.

Remember when Paul, the titled Englishman in Three Weeks, is enchanted by the mysterious royal stranger at a hotel in lucern, is invited to her rooms, and in a dizzy perfume of tuberoses, lilies of the valley, and roses, roses, roses, falls madly in love?

His queen reclines on a couch covered with a tiger skin. (Elinor Glyn liked tiger skins. She received five as gifts, one from Lord Curson and one from Lord Milner.)

“Then a madness of tender caressing seized her. She purred as a tiger might have done, while she undulated like a snake. She touched him with her fingertips, she kissed his throat, his wrists, the palms of his hands, his eyelids, his hair. Strange subtle kisses, unlike the kisses of women. And often, between her purring she murmured love-words in some fierce language of her own, brushing his ears and his eyes with her lips the while.”

Literally thousand of people, including American men and women, wrote Glyn for advice on love. She found that even Rudolph Valentino had a lot to learn in the art of making love convincingly before a camera.

“Do you know,” she would murmur, “he had never even thought of kissing the palm, rather than the back of a women’s hand, until I made him do it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Vain, willful, courageous, spirited

Glyn was a beautiful woman until the day she died. She worked at it. Two of her startling aids to beauty: To scrub the face hard with a dry nailbrush until the skin glowed crimson (Not recommended!), and to sleep with one’s head to the magnetic north (pure common sense, she said).

She was always impeccably, fashionably gowned in clothes designed by her sister Lucile, Lady Duff-Gordon.

Glyn earned a great deal of money, and she spent it recklessly. One of her sons-in-law, Sir Rys-Williams, finally organized a limited liability company to hold copyrights of all her works and receive all royalties, so that she would be protected from her own wild investments and lavish spending.

Anthony Glyn wrote his biography of his grandmother “as objectively as possible, consistent with the demands of filial piety,” using material from Elinor’s published and unpublished books, articles, film scripts, the intimate diary that she kept intermittently from 1879 to 1942, her journals, notebooks, recollections of her family, friends, and business associates, press clippings, and hundreds of her own inimitable letters.

Vain, willful, romantic, and snobbish, Elinor Glyn also was quite resourceful, full of courage, pride, energy, and spirit. The world bought her awful love stories and rolled in their eroticism like catnip. The life story of this woman is delightful and fascinating.

(reviewed by Ruth Smith, July 17, 1955)

Leave a Reply