Cimarron by Edna Ferber — the 1930 Novel and the 1931 Film

By Taylor Jasmine | On March 21, 2022 | Updated August 9, 2022 | Comments (0)

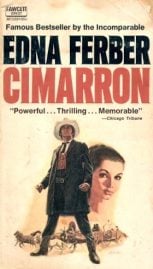

Cimarron by Edna Ferber was a 1930 novel by the prolific American author that was quickly adapted to film, earning accolades and winning 1931’s Academy Award for Best Picture.

Though it wasn’t the first of Ferber’s novels to be adapted to film, it was a far more expansive (and expensive) production. It paved the way for more Hollywood blockbusters based on her books.

Cimarron (from a Spanish derivation meaning “wild” or “unruly”) takes for its subject the Land Run in Oklahoma territory in 1889. A 1930 review described the book in a nutshell:

“It depicts the opening up of that great territory known as the Run of ’89 — the fantastic scramble when oil was discovered. The story is told through the experience of Yancey Cravat and his young wife who went to seek their fortunes in the new territory. Always a mysterious character with a shadowy past, Cravat is one of Miss Ferber’s best creations.”

Though we don’t often quote Wikipedia so extensively, the explanation of the historic concept of the “land run” or “land rush” found there is quite helpful as background for fully appreciating the novel. From the entry for Cimarron:

“A land run or land rush was an event in which previously restricted land of the United States was opened to homestead on a first-arrival basis. Lands were opened and sold first-come or by bid, or won by lottery, or by means other than a run …

For former Indian lands, the Land Office distributed the sales funds to the various tribal entities, according to previously negotiated terms. The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 was the most prominent of the land runs while the Land Run of 1893 was the largest …

The Cimarron Territory was an unrecognized name for the No Man’s Land, an unsettled area of the West and Midwest, especially lands once inhabited by Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Sioux. In 1886 the government declared such lands open to settlement …

The novel is set in Oklahoma of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It follows the lives of Yancey and Sabra Cravat, beginning with Yancey’s tale of his participation in the 1893 land rush.

They emigrate from Wichita, Kansas, to the fictional town of Osage, Oklahoma with their son Cim and—unknowingly—a Black boy named Isaiah. In Osage, the Cravats print their newspaper, the Oklahoma Wigwam, and build their fortune amongst Indian disputes, outlaws, and the discovery of oil in Oklahoma.

Cimarron was a sensation in America and came to epitomize an era in American history. It was the best-selling novel of 1930, as it provided readers an outlet to escape their present suffering in the Great Depression.”

Ferber’s novels often wove in themes of social justice and feminism, and in intent, at least, Cimarron was no exception. Suffice it to say that it wasn’t a hit in Oklahoma, with its critical views on the treatment of Native Americans.

Yet, Ferber falls prey to stereotyping, no matter how unintentional. An excellent essay on rediscovering 20th-century middlebrow literature on MassHumanities observes:

“In recognizing Ferber’s own colonialist attitudes—even as she is writing an anti-colonial narrative—we must keep in mind not only the era in which she was writing, but also the fact that she intended Cimarron as satire and expressed frustration that it was most often considered a straightforward Western narrative.

And it is fascinating to see how Ferber, writing almost a century ago, deals with issues of race and ethnicity that we are still dealing with today.

Through a series of subplots, Ferber sets forward different approaches to these issues, ranging from full assimilation of new immigrants and other outsider communities to a multiculturalism that accepts and incorporates ethnic diversity to an extreme nativist call for the “humane but effective” extermination of Native Americans and other minorities.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Most contemporaneous reviews (of both the book and the subsequent film) were generally favorable. The one following was less glowing than average, critiquing the way that Yancey’s character development (or lack thereof) was portrayed:

A 1930 review: “Ferberizing the Indian Territory”

From the Cincinnati Enquirer, March 29, 1930: Despite the almost incredible gusto of this new Ferber story, the swiftness, sustained fortissimo of its color-swept notes, and the stamping narrative that makes Showboat seem almost a tender idyll in comparison — there is still a hollow sound about it, as of someone drumming in a well.

The characters never seem to come whole, and one constantly has the feeling that all the bright show, glamour, and clangorous background of Oklahoma in the land rush of 1889, its gaudy pioneer growth and later furious scuffle for oil, are arranged and elaborated to draw attention from the essential emptiness of inferior people.

For Edna Ferber, this is strange. Gaylord Ravenal of Showboat was a handsome, weak dandy, fascinating but hardly memorable. But in his very weakness, he was human and real.

Yancey Cravat in Cimarron is far more picturesque than Ravenal — a great, vital fellow, lawyer and editor, spouter of classics and fine language, possessing the added fascination of a “past.” When he came to Wichita, Kansas, and established his fiery newspaper, he swept Sabra Venable off her feet and married her.

As the story opens, Yancey, with characteristic volubility and enthusiasm, is describing to Sabra and her people the great land run of 1889. And he does a mighty fine job of it, as Miss Ferber has done throughout the book in all descriptive passages.

But whether the fantastic Yancey is haranguing his relatives by marriage, supplying for a while as citizen and editor the core of a new rough community in Oklahoma, turning to drunkenness and wandering afar from the rather chilly bosom of his family, or dying on a heroic note with a proper quotation from Ibsen— he is still a shell.

We never see within him, nor do we get any real humanity out of his wayward son or hard-boiled daughter. With Sabra, his wife, it’s not the same. Sabra, like virtually all of Miss Ferber’s women, is the best man in the family. The forceful Yancey may turn out to be a dreamer and a fool; at the same time, Sabra climbed to editorship, power, and Congress. She becomes the center and symbol of Osage.

Her character is full-blown. Through her political standing, she becomes the instrument of a thorough, almost minute study of the gradual refinement of a civilization, and of the same social problems that exist today.

Sabra is the product of Miss Ferber’s most acute realism, and it’s because her husband and children are evaluated through her reflections that they have no real entity of their own. It’s almost as if they existed only in her mind.

But in Cimarron, the scene is the hero — or, as Miss Ferber would probably prefer it, the heroine. It is splendidly recorded, and gives the book, particularly the early part, that sense of exciting haste, confusion, and color that makes Cimarron one of Miss Ferber’s most fascinating novels, even if it is far from being her best.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Cimarron: The 1931 film

Hollywood was already familiar with Edna Ferber by the time Cimarron appeared in print. A few of her books were made into silent films, and the advent of “talkies” made her sweeping sagas even more promising to produce as movies.The Camden (NJ) Courier-Post wrote:

“I will say for RKO they are certainly buying plenty of good material. Their latest adventure is Cimarron, Edna Ferber’s latest book, telling the story of the opening of Oklahoma as a state. Miss Ferber generally hits the best-seller mark or close to it, and RKO had to reckon with that when they paid a fancy price for this piece of fiction. I am told it cost close to $100,000 for the screen rights but of course, this may be a trifle exaggerated.”

It was not an exaggeration. A tough businesswoman (even as she claimed not to be), Ferber sold film rights for Cimarron to RKO for between $100,000 to $125,000 — a huge amount in those days, as it would be in today’s dollars.

The U.S. was already sinking into the depths of the Great Depression when the film was made and released. It was a big-budget film, directed by Wesley Ruggles and starring Richard Dix as Yancey Cravat and Irene Dunne as Sabra Cravat.

Though it was hugely well received and won the Academy Award for Best Picture, it didn’t do as well as expected at the box office; the budget was not recouped. Still, that didn’t stop Hollywood from continuing to mine Ferber’s books, Showboat (1936) and Giant (1956) among the future adaptations.

The film version of Cimarron stood out for its sympathetic portrayal of and attitude toward Native Americans, something atypical in mid-20th-century films. It did suffer for its minstrel-y portrayal of Isaiah, the young Black boy, a choice likely not approved of by Ferber.

Cimarron was remade in 1960, though that adaptation wasn’t nearly as much of a critical success as the first iteration, and generally received unfavorable reviews.

The following review, though devoid of much insight, is typical of the gushing praise the 1931 film received. The reviewer seems to have missed any of the messages from the book that survived in the adaptation:

From the Tyler Daily Courier-Times (Tyler, TX), March 15, 1931: A stirring and beautiful dramatization of Edna Ferber’s justly celebrated novel, it features an exceptional cast headed by Richard Dix, Irene Dunne (a beautiful newcomer to the screen who seems destined to become an outstanding favorite), Edna May Oliver, Estelle Taylor, George Stone, and many others in noteworthy character parts.

… In Cimarron is invested stirring drama, stark beauty, daring, an adventure on a plane seldom seen on the screen. It’s a story of compelling interest, a well-knit, suspense-filled drama that follows a man and his wife from the turbulent, rough-and-tumble days of the Oklahoma frontier down to our own day.

The spirit of the pioneer era that Edna Ferber so gloriously recorded in her novel has been captured in this screen dramatization. For the indomitable spirit of the pioneer, like a symbol of strength, pervades every moment of Cimarron.

The main character, Yancey Cravat, is portrayed by Richard Dix. With his young wife and son, Yancey sets out to the Oklahoma frontier of 1889, eager to set up a home and establish himself and his family in the “promised land.”

Yancey is a God-fearing, truth-loving man. He becomes in turn a militant, courageous editor, and an honest, fearless lawyer. But deep in his heart is the spirit of a true adventurer, a leader, and a fighter.

This spirit causes him to inwardly despise safety and comfort, and forces him to seek new lands, new conquests. It compels him to desert his family for years on end in pursuit of new ideals. The story of Yancey’s colorful life, which extends right up to 1929, is filled with stirring adventures the likes of which are seldom seen on screen.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Show Boat: From Page to Stage to Film

. . . . . . . . .

Leave a Reply