Lydia Maria Child, American Author & Social Reformer

By Nava Atlas | On March 22, 2018 | Updated August 17, 2022 | Comments (1)

Lydia Maria Francis Child (February 11, 1802 – October 20, 1880) was a prolific American author, social reformer, journalist, and abolitionist.

Born in Medford, Massachusetts, she was educated despite the disapproval of her father, a baker, who thought she ought not to read at all.

But Lydia’s appetite for learning was voracious, and the books she devoured were supplied primarily by her brother Convers Francis, who later became a Unitarian minister and professor at Harvard Divinity School.

Early encounters with Native Americans

When Lydia was twelve, her mother died and she was sent to live with an older married sister in Norridgewock, Maine. There she had contact with native Americans of the Penobscot and Abenaki tribes and visited them in their wigwams.

According to Elaine Showalter, author of A Jury of Her Peers, as a child, Lydia “saw a Penobscot woman who had borne a child and then walked four miles through the snow. She also met the Penobscot chief Captain Neptune.” These early encounters and friendships informed her lifelong (albeit complicated) advocacy on behalf of Native Americans.

First novels and a challenging marriage

Hobomok (1824) was published under the pseudonym “An American,” because she was warned that “no woman could expect to be regarded as a lady after she had written a book.”

Set during the colonial period, the story concerns the marriage of a white woman, Mary Conant, to Hobomok, the titled Native American, and how she raised her son in white society after the death of her husband. The mixed marriage theme was quite taboo, and at first, the novel fared poorly.

The North American Review wrote that the novel was “unnatural” and “revolting to every feeling of delicacy.” Lydia was a good self-promoter, though, and through her efforts among the Boston literati, the novel was read and became successful.

From 1826 to 1834, Lydia edited The Juvenile Miscellany, the first American children’s monthly periodical.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Insightful Quotes by Lydia Maria Child

. . . . . . . . . . .

Her second novel, The Rebels, or Boston Before the Revolution (1825) was even less favorably reviewed than Homobok had at first been. One critic who was kind to the book was David Lee Child, a brilliant but erratic Boston lawyer and journalist, who was so fast and loose with his writing that he earned the nickname David Libel Child. Reader, she married him.

From the time Lydia hitched her fortunes to David’s in 1828, her life was one of work and worry. She continually had to earn money to pay his legal costs and debts.

Like Louisa May Alcott who came slightly after her, she considered writing as a way to make a living, rather than as a means of artistic expression. Lydia desperately needed money, and in addition to writing, she also took in boarders and taught school.

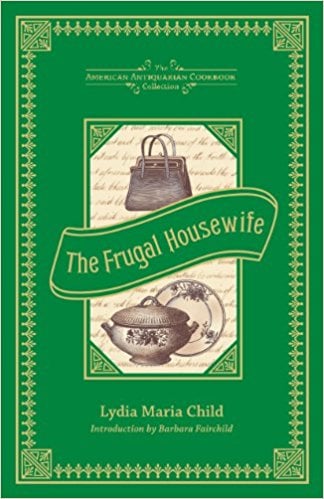

The Frugal Housewife

In 1829, Lydia published The Frugal Housewife, which was “dedicated to those who are not ashamed of economy.” In addition to basic recipes, she also provided advice on basic matters of housekeeping and home repairs. It wasn’t a rarified view of home life, and Lydia was critiqued for her “indelicacy.”

Still, the book was wildly successful. Emphasizing frugality in the kitchen and self-reliance by women in the household, it went through dozens of printings, and was the first domestic cookbook to rival Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery (1796).The Frugal Housewife is still in print.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Taking up the cause of abolition

In the early 1830s, Lydia and David child began to devote themselves to the anti-slavery cause, and in 1833 she published An Appeal for that Class of Americans called Africans, a stirring portrayal of the evils of slavery, and an argument for immediate abolition. The book was influential in winning recruits to the anti-slavery cause.

Lydia remained devoted to the cause of abolition. From 1840 to 1844, Lydia and David edited the Anti-Slavery Standard in New York City. After the Civil War, she worked on behalf of the rights of freed slaves. She also returned to her early interest in the rights of Native Americans.

The strangely tainted legacy of Lydia Maria Child

As she grew older, Lydia’s views had become tainted with conservatism and bias. In her 1868 book, An Appeal for the Indians, she wrote: “How ought we to view the peoples who are less advanced than ourselves?” and professed “considerable repugnance” toward them.

It’s unclear why such a passionate social reformer, whose pen flowed so freely, should have ended up in this manner. Elaine Showalter observed:

“It is ironic that Child, who started out as one of the most passionate, defiant, and iconoclastic writers of her generation, especially in her hatred of Calvinism, her resistance to patriarchal tyranny, and her opposition to American oppression of its ‘less advanced’ peoples, should end by repeating the psychological patterns she had so brilliantly analyzed and condemned.

Child’s literary career was marked by debate and duality; in her fiction she structured plots around people with complex choices between two radically different ways of life … but toward the end of her life, Child found herself ‘too old to write imaginative things.'” (from A Jury of Her Peers, 2009)

Despite her creeping conservatism, she was a founding member of the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association and wrote The History of the Conditions of Women in Various Ages and Nations, which influenced the generation of suffragists that came after her.

The messy and contradictory end to her reputation as a reformer notwithstanding,Lydia Maria Child is considered a highly influential 19th-century author and reformer. She died in Wayland, Massachusetts, on October 20, 1880, at age 78.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Child is the author of the famous Thanksgiving poem,

“Over the River and Through the Wood”

More about Lydia Maria Child

On this site

Major works

This is but a partial list of Lydia Maria Child’s prolific output:

- Hobomok (1824)

- The Rebels (1825)

- The (American) Frugal Housewife (1829), one of the earliest American books on domestic economy

- The Mother’s Book (1831), a pioneer cookbook republished in England and Germany

- The Girls’ Own Book (1831)

- History of Women (2 vols., 1832),Good Wives (1833)

- The Anti-Slavery Catechism (1836)

- Philothea (1836), a romance of the age of Pericles

- Letters from New York (2 vols., 1843-1845)

- Fact and Fiction (1847)

- The Power of Kindness (1851)

- Isaac T. Hopper: a True Life (1853)

- The Progress of Religious Ideas through Successive Ages ; (3 vols., 1855)

- Autumnal Leaves (1857)

- Looking Toward Sunset(1864)

- The Freedman’s Book (1865)

- A Romance of the Republic (1867)

- Aspirations of the World (1878)

More information

Read and listen online

Articles, News, etc.

Thanks for the catch, Katrina — it’s supposed to be 1828, and has been updated.